Soil provides anchorage and nutrients for plants

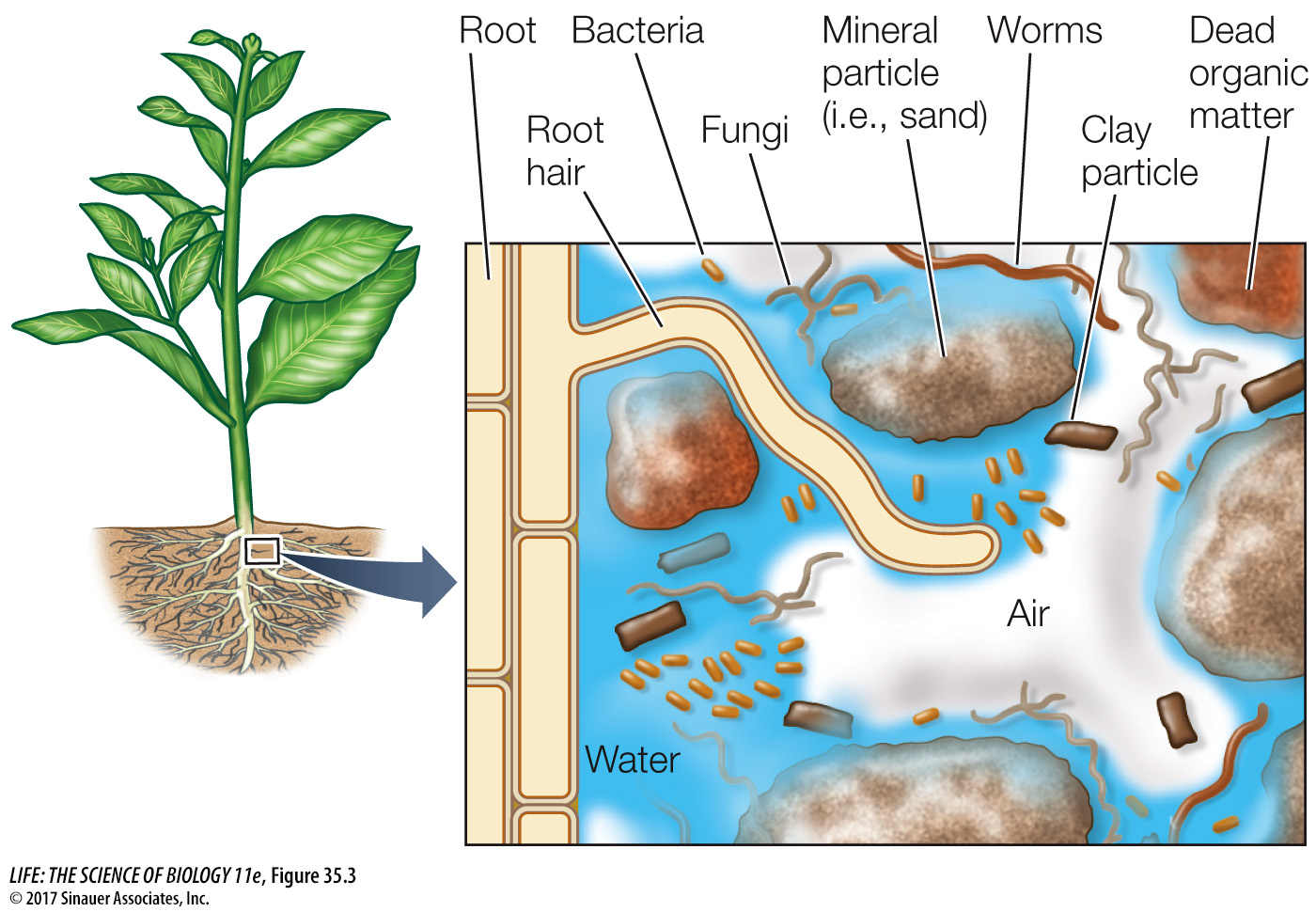

Soils have living and nonliving components (Figure 35.3). The living components include plant roots as well as populations of bacteria, fungi, protists, and animals such as earthworms and insects. The nonliving portion of the soil includes rock fragments ranging in size from large stones to sand to silt, and finally to tiny particles of clay that are 2 micrometers (μm) or less in diameter. Soil also contains water and dissolved mineral nutrients, air spaces, and dead organic matter. The air spaces in soil contain O2. Typical percentages of these components are:

Particles: 45% Water: 25% Air: 25% Organisms: 5%

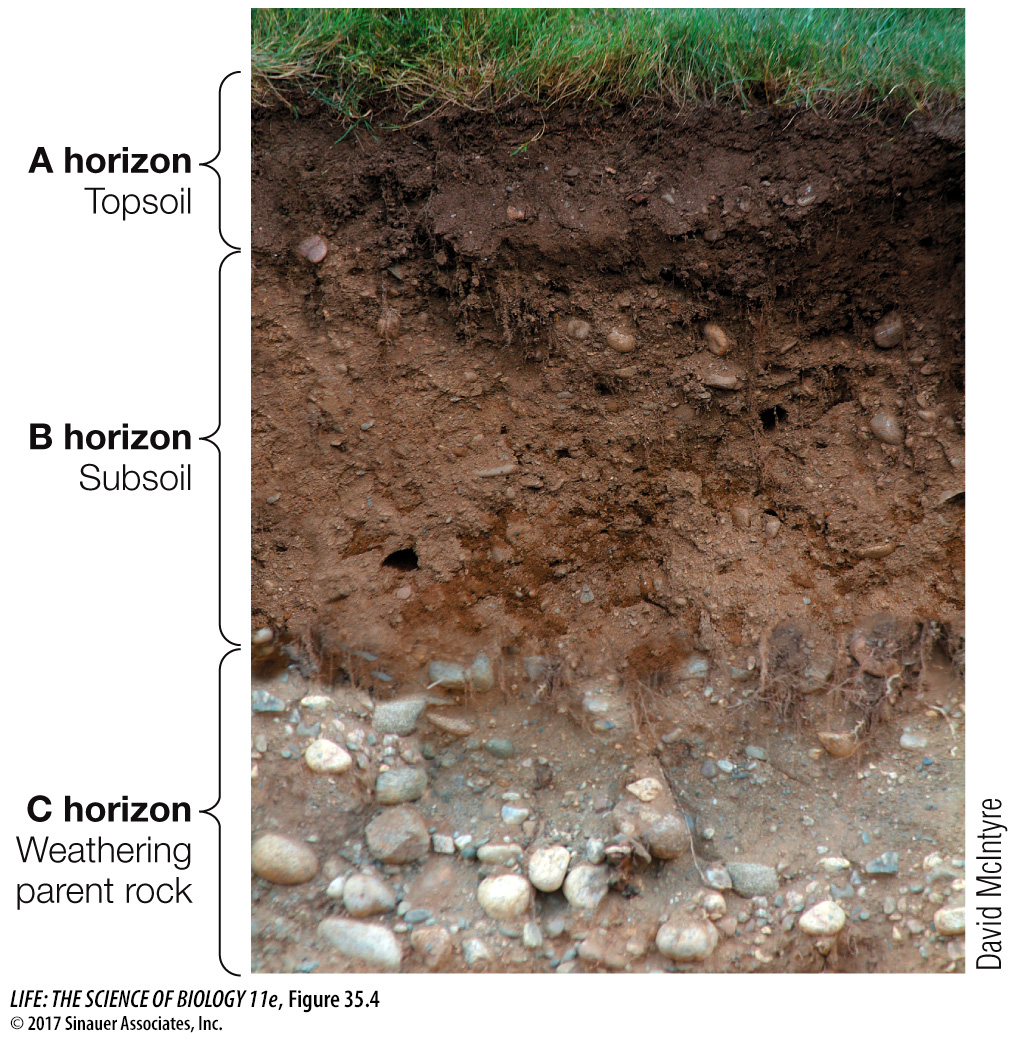

Although soils vary greatly, almost all of them have a soil profile consisting of several recognizable horizontal layers, called horizons, lying on top of one another. Soil scientists recognize three major horizons—

The A horizon is the topsoil that supports the plant’s nutrient needs. It contains most of the soil’s living and dead organic matter.

The B horizon is the subsoil, which accumulates materials from the topsoil above it and from the parent rock below.

The C horizon is the parent rock, also called bedrock, which is in the process of breaking down to form soil.

Soil fertility is a soil’s ability to support plant growth. A topsoil’s fertility is determined by several factors. Topsoils vary greatly in their proportions of sand, silt, and clay, and this influences their ability to support plant growth. For example, mineral nutrients tend to be leached from the upper soil horizons—

In addition to mineral particles, soils contain dead organic matter, largely from plants. Soil organisms break down dead leaves and other plant organs on the ground into a substance called humus. This material is used as a food source by microbes that break down complex organic molecules and release simpler molecules into the soil solution. Humus also provides air spaces that increase O2 availability to plant roots.