Plants don’t always win the arms race

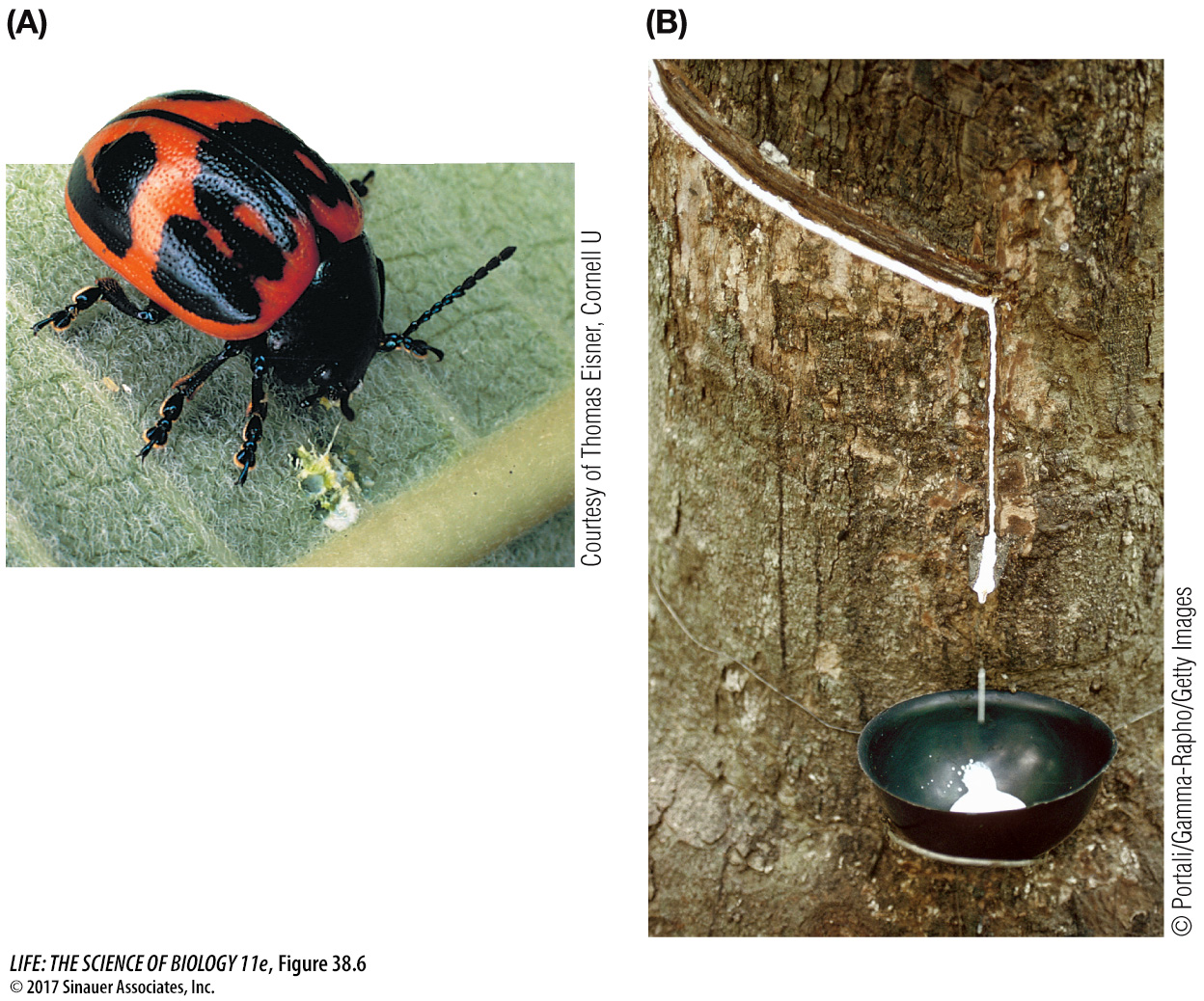

Milkweeds such as Asclepias syriaca store their defensive chemicals in latex in specialized tubes called laticifers, which run alongside the veins in the leaves. When damaged, a milkweed releases copious amounts of toxic latex from its laticifers. Field studies have shown that most insects that feed on neighboring plants of other species do not attack laticiferous plants, but there are exceptions. One population of beetles that feeds on A. syriaca exhibits a remarkable prefeeding behavior: these beetles cut a few veins in the leaves before settling down to dine. Cutting the veins causes massive latex leakage from the adjacent laticifers and interrupts the latex supply to a downstream portion of the leaf. The beetles then move to the relatively latex-

When latex dries, it becomes rubbery. That’s a good adjective, because we have exploited the sticky, moldy properties of dry latex from the tree Hevea brasiliensis to turn it into rubber for tires, shoes, adhesives, and condoms, to name a few products (Figure 38.6B). Because Japan occupied the regions of the world where rubber trees grow, during World War II U.S. and British chemists investigated ways to make synthetic rubber. They analyzed latex, determined its composition of hydrocarbons, and then made rubber in the lab. Today, half of the rubber used worldwide is synthetic.