AIDS is an immune deficiency disorder

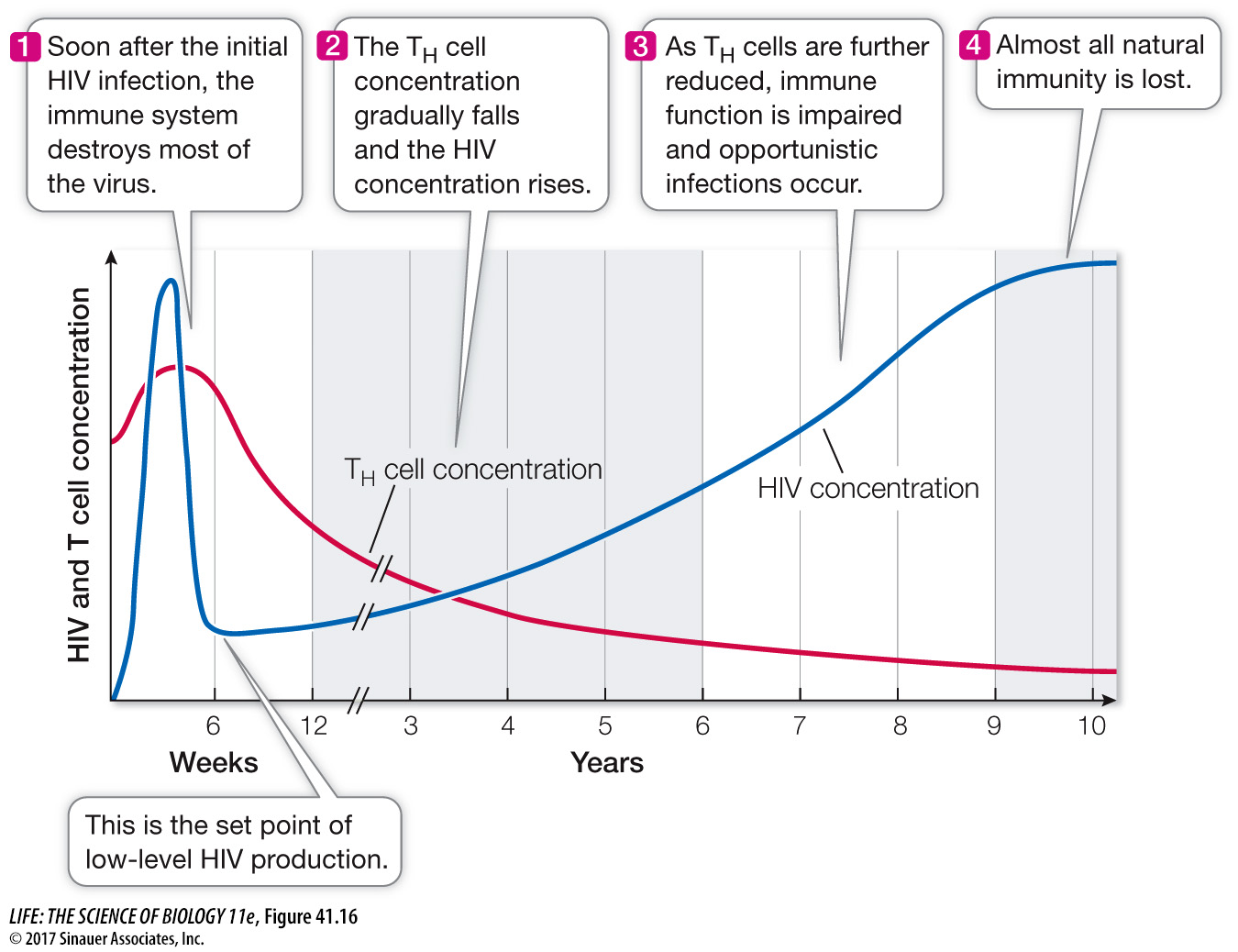

There are several inherited and acquired immune deficiency disorders. In some individuals, T or B cells never form; in others, B cells lose the ability to give rise to plasma cells. In either case, the affected individual is unable to mount an adaptive immune response and thus lacks a major line of defense against pathogens. The TH cell is perhaps the most central component of the immune system because of its essential roles in both the humoral and cellular immune responses (see Figure 41.6). This cell is the target of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the retrovirus that results in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

HIV can be transmitted from person to person in body fluids containing the virus (such as blood, semen, or vaginal fluid). The recipient tissue is either blood (by transfusion) or a mucous membrane lining an organ (the mucus contains a high concentration of lymphocytes). HIV initially infects macrophages, TH cells, and antigen-

During this dormant period, people carrying HIV generally feel fine, and their TH cell levels are adequate for them to mount immune responses. Eventually, however, the virus destroys the TH cells, and their numbers fall to the point where the infected person is susceptible to infections that the TH cells would normally eliminate. These infections result in conditions such as Kaposi’s sarcoma, a skin tumor caused by a herpes virus; pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii; and lymphoma tumors caused by the Epstein–

HIV has been intensively studied. This has resulted in the development of drugs targeted to HIV proteins, such as the reverse transcriptase that makes cDNA from the viral RNA, and the viral protease that cuts the large precursor viral protein into its final active proteins. Treatment with combinations of such drugs has had spectacular success. Getting AIDS before the 1990s was a death sentence, with few sufferers surviving beyond a year or two. Today the survival of a treated, infected person is decades longer. Unfortunately, like many medical treatments, HIV drugs are not available to all who need them—