The evolution of vertebrate reproductive systems parallels the move to land

The earliest vertebrates evolved in aquatic environments. The closest living relatives of those earliest vertebrates are modern-

Amphibians were the first vertebrates to live in terrestrial environments. They dealt with the challenge of a dry environment by returning to water to reproduce, as most amphibians still do today.

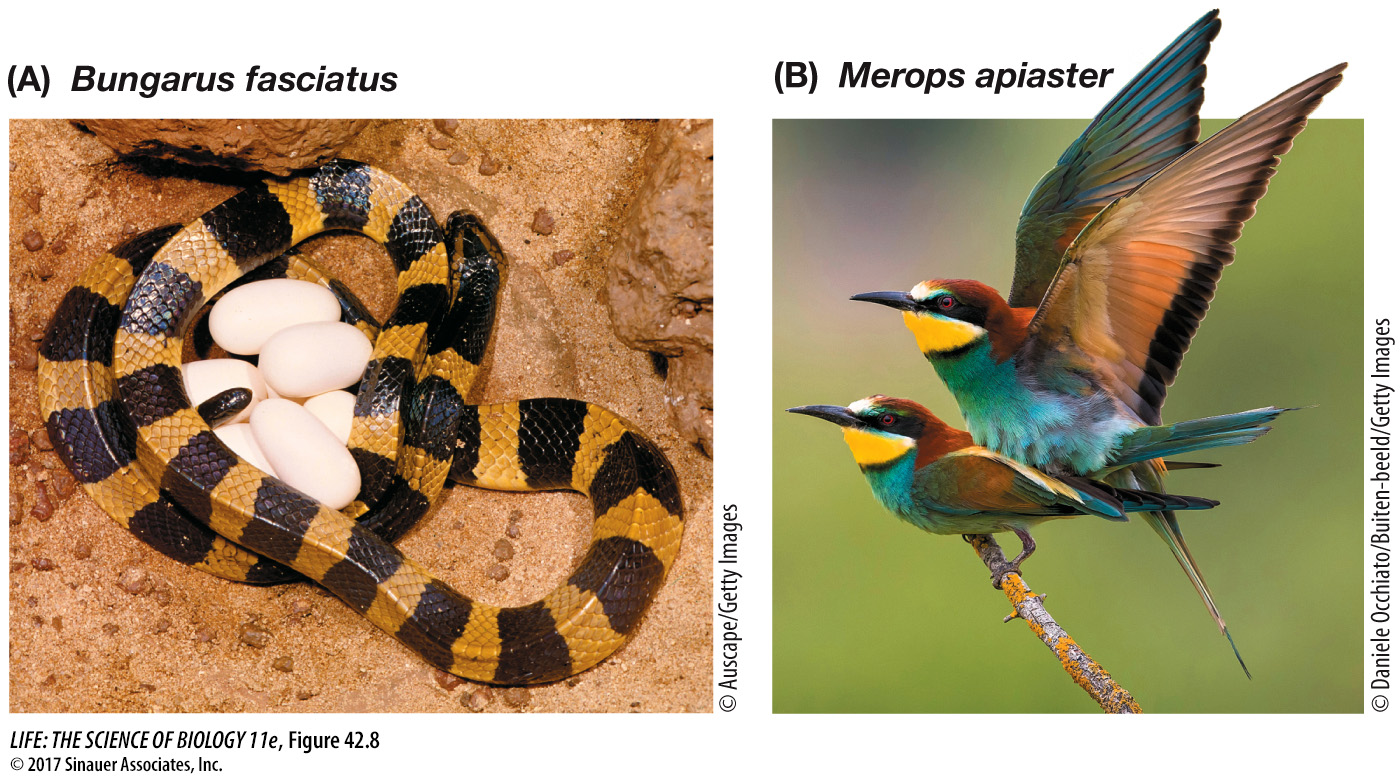

Reptiles were the first vertebrate group to solve the problem of reproduction in the terrestrial environment (Figure 42.8). Their solution was the amniote egg (see Figure 32.19A). A hard or leathery shell protects the embryo and impedes water loss while allowing the diffusion of oxygen into the egg and carbon dioxide out of the egg. The eggshell creates an obvious problem for fertilization. Sperm cannot penetrate the shell, so they must reach the egg before the shell forms. Hence internal fertilization and the evolution of accessory sex organs were necessary for the evolution of the amniote egg.

Male snakes and lizards have paired hemipenes (hemipenis, sing.), which can be engorged with blood and thereby extruded from the male’s body. Only one hemipenis is inserted into the female’s reproductive tract. It is usually rough or spiny at the end to achieve a secure hold while sperm are transferred down a groove on its surface. Retractor muscles pull the hemipenis back into the male’s body when mating is completed. Some evolutionarily ancient bird species have erectile penises that channel sperm along a groove into the female’s reproductive tract. Birds with more recent evolutionary origins, however, do not have erectile penises; instead, the male and female simply bring their genital openings (cloacae, sing. cloaca) close together to transfer sperm. Usually this involves the male standing on the female’s back (see Figure 42.8B).

All mammals practice internal fertilization. Then, all except the prototherian mammals retain the developing embryo for some time in the female reproductive tract. Prototherian mammals (the monotremes; see Figure 32.26) lay eggs. The other mammals (the therians) vary enormously as to the developmental stage of their offspring at the time of birth. As you saw at the beginning of the chapter, the tammar wallaby is extremely immature at birth. By comparison, a horse foal can stand up soon after birth and is able to run within hours.