Invertebrates have a variety of visual systems

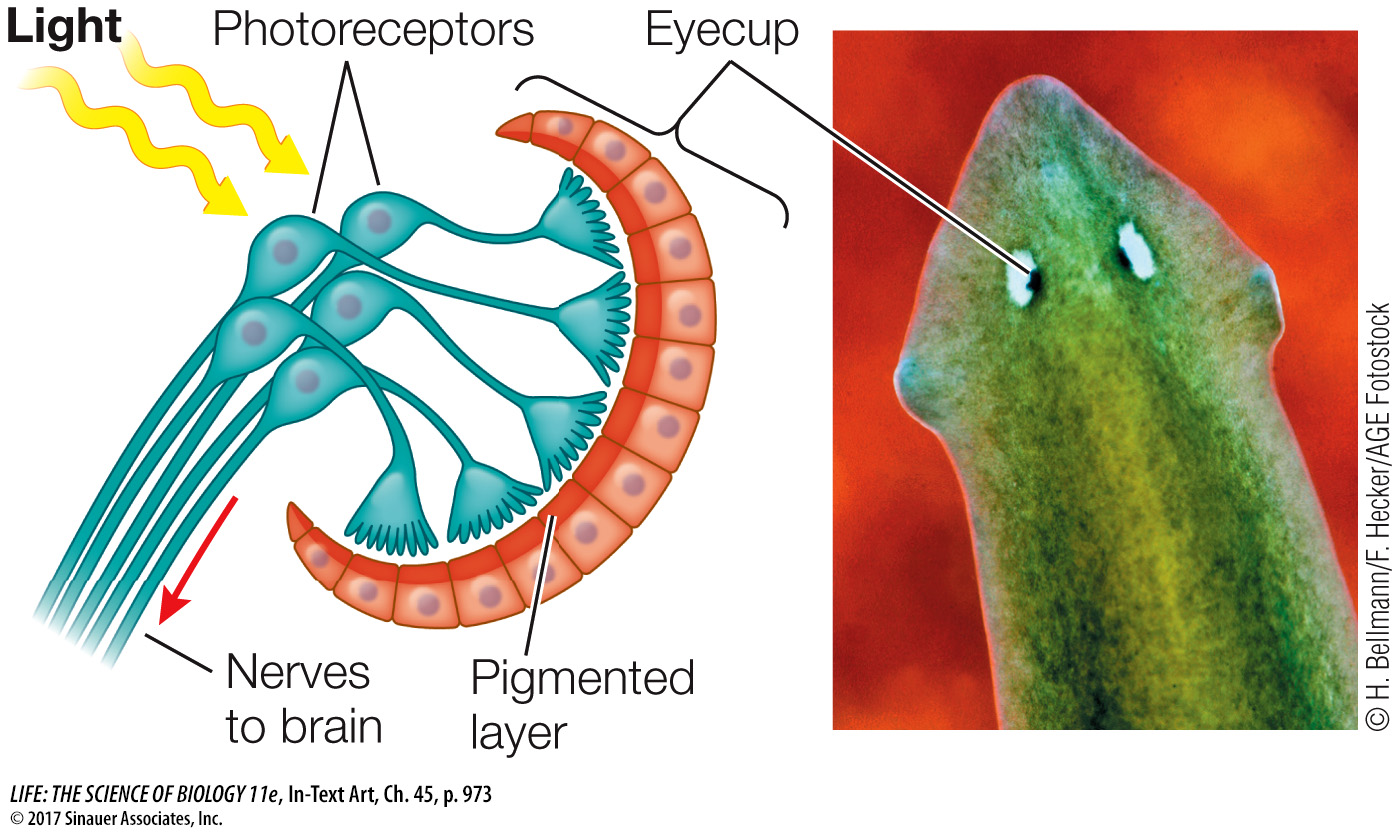

Photoreceptors and visual pigments are incorporated into a variety of visual systems, from simple to complex. Flatworms obtain directional information about light from photoreceptor cells that are organized into eye cups. The eye cups are paired, bilateral structures, each partly shielded from light by a layer of pigmented cells lining the cup.

The photoreceptors on the two sides of the animal are unequally stimulated unless the animal is facing directly toward or away from a light source. The flatworm generally uses directional information from the eye cups to move away from light.

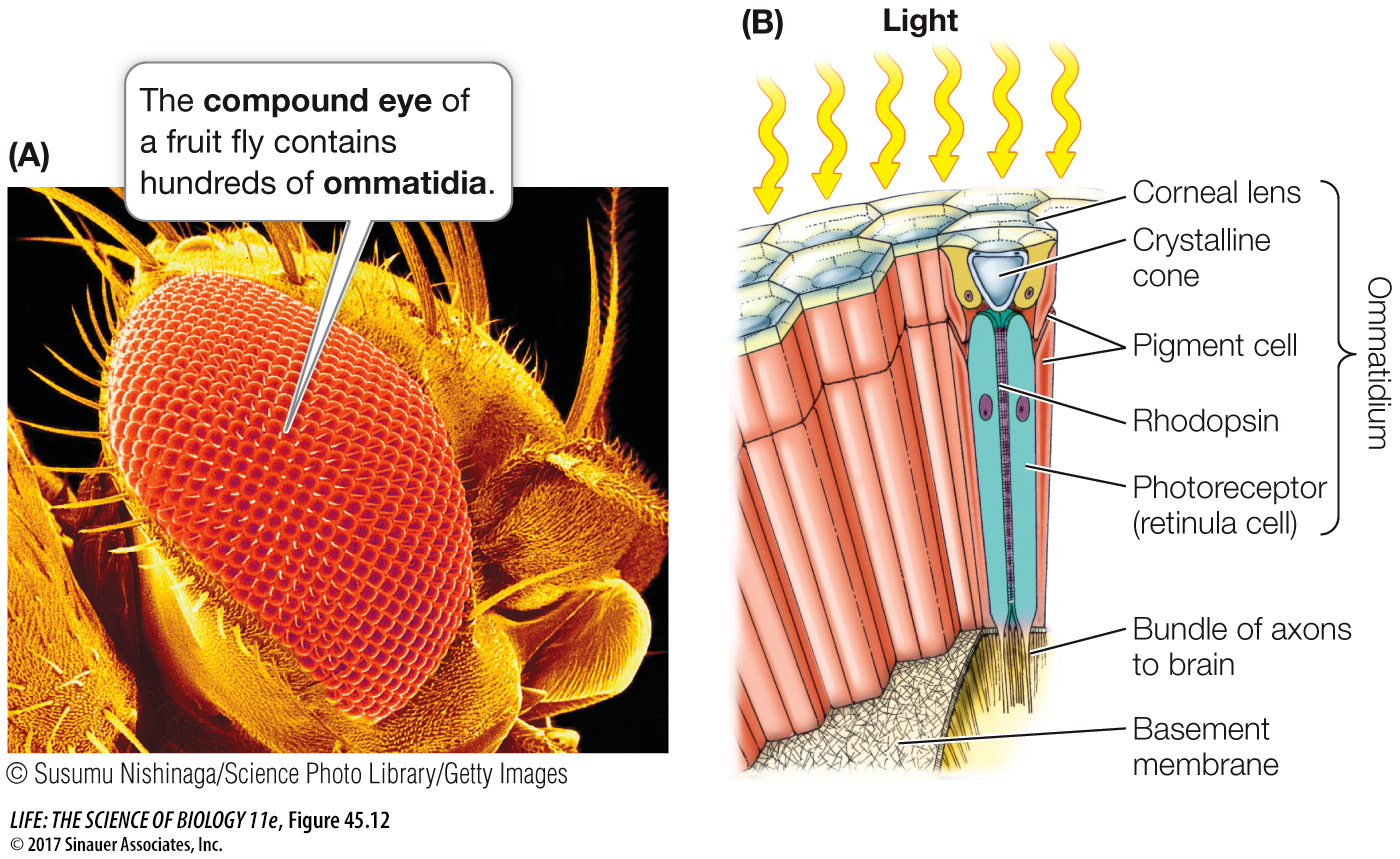

Arthropods have compound eyes that provide them with information about patterns in the environment. These eyes are called compound because each eye consists of many optical units called ommatidia (singular ommatidium), each with its own narrow-

Each ommatidium has a lens that directs light onto photoreceptor cells. Flies, for example, have eight elongated photoreceptors in each ommatidium. The inner borders of the photoreceptors are covered with microvilli that contain a photosensitive pigment that traps light. Axons from the photoreceptors send the light information to the nervous system. Since each ommatidium of a compound eye is directed at a slightly different part of the visual world, only a low-