Platelets are essential for blood clotting

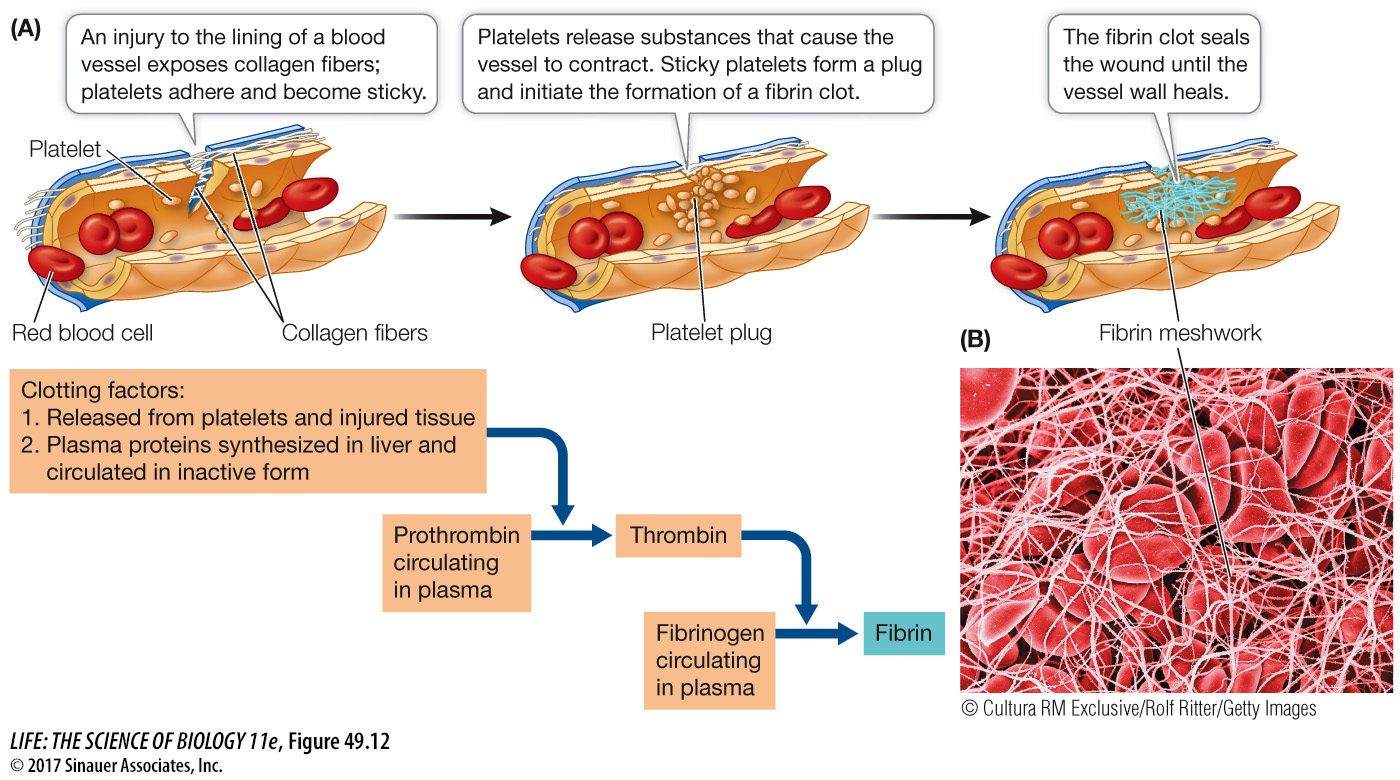

Besides producing erythrocytes and leukocytes, the bone marrow stem cells described in Key Concept 41.1 also produce cells called megakaryocytes. Megakaryocytes are large cells that remain in the bone marrow and release platelets into the circulation. A platelet is a tiny fragment of a cell without cell organelles, but it is packed with enzymes and chemicals necessary for its function: sealing leaks in blood vessels and initiating blood clotting (Figure 49.12).

Damage to a blood vessel exposes collagen fibers. An encounter with collagen fibers activates platelets. The platelet swells, becomes irregularly shaped and sticky, and releases chemicals that activate other platelets and initiate the clotting of blood. The sticky platelets also form a plug at the damaged site.

Blood clotting requires many steps and many clotting factors, most of which are circulating in the blood in an inactive form. The absence of any one of these proteins can impair clotting, resulting in excessive bleeding. Because the liver produces most of the clotting factors, liver diseases such as hepatitis and cirrhosis can result in excessive bleeding. People with hemophilia experience uncontrolled bleeding because of a genetic inability to produce a clotting factor.

Blood clotting factors participate in a cascade of chemical activations of other substances circulating in the blood. The cascade begins with damage to a blood vessel or other tissue that exposes the blood to proteins such as collagen that are normally separated from the blood by endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This exposure activates platelets and begins the clotting factor cascade. The end result of this cascade is to convert an inactive circulating enzyme, prothrombin, to its active form, thrombin. Thrombin cleaves molecules of fibrinogen, a plasma protein, forming insoluble threads of fibrin. The fibrin threads form the meshwork that binds platelets, seals the vessel, and provides a scaffold for the formation of scar tissue (see Figure 49.12).