Herbivores rely on their microbiota to digest cellulose

Cellulose is the primary component of plant cell walls, and is therefore the principal component of the food of herbivores. Most herbivores, however, cannot produce cellulases, the enzymes that break down cellulose. (Exceptions include earthworms, shipworms, and the silverfish that eat books and stored papers.) From termites to cattle, herbivores rely on the microbiota of their digestive tracts to digest cellulose.

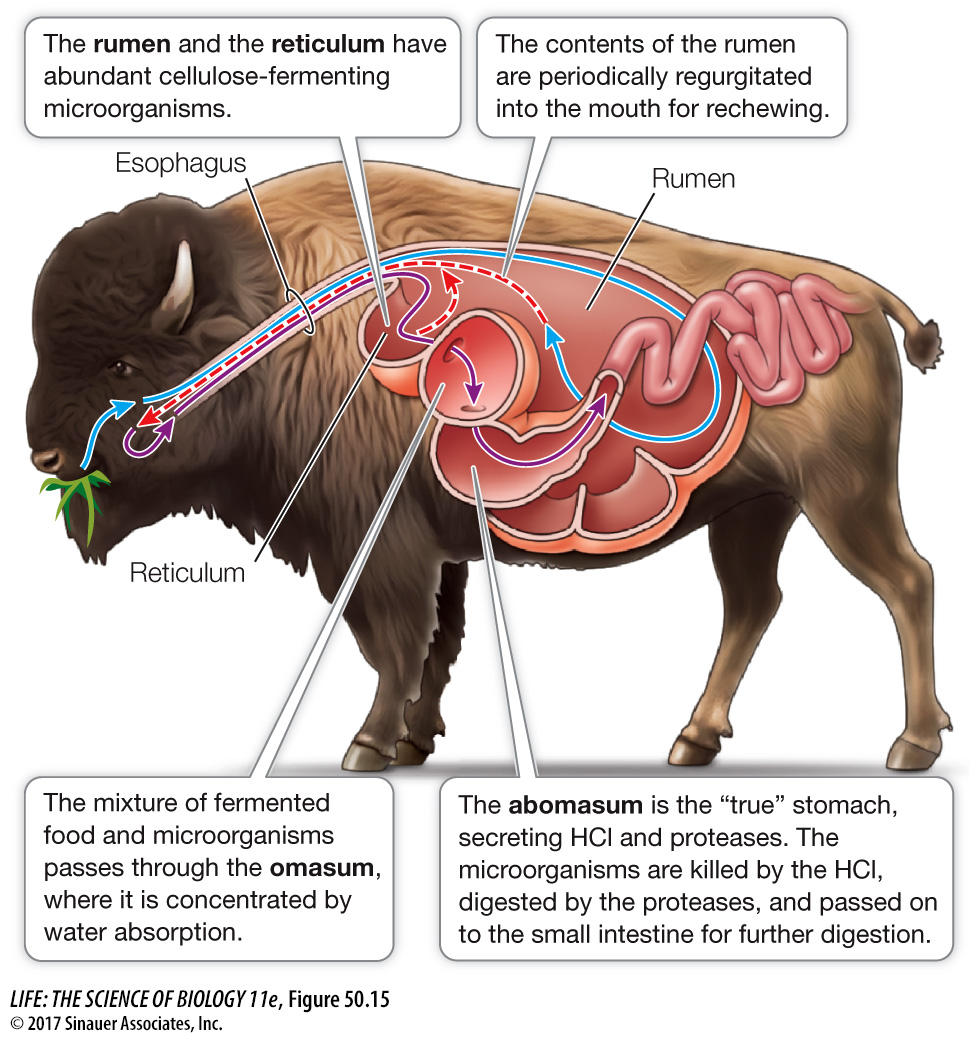

Ruminants (cud chewers) such as cattle ferment their plant-

Q: Functionally, why do the rumen and reticulum come before the true stomach, the abomasum?

The position of the rumen and reticulum before the abomasum allows large populations of gut microbiota to grow and break down the ingested plant material before passing into the true stomach, where they are killed by stomach acid.

Enormous numbers of microorganisms leave the rumen along with the partially digested food. This mass is concentrated by water absorption in the omasum before it enters the true stomach, the abomasum, where the microorganisms are killed by secreted hydrochloric acid, partially digested by proteases, and passed on to the small intestine for further digestion and absorption. A cow derives more than 100 grams of protein per day from digestion of its microbiota. The rate of multiplication of microorganisms in the rumen offsets their loss, so a well-

Some mammalian herbivores have a microbial fermentation chamber called a cecum extending from the large intestine. An example is the rabbit (see Figure 50.7). Since the cecum empties into the large intestine, absorption of nutrients produced by the microorganisms in the cecum is inefficient because of the limited surface area of the large intestine. Such species frequently produce two kinds of feces—