The brain plays a major role in regulating food intake

Multiple brain areas and signals are involved in the regulation of food intake. Long ago it was discovered that damaging a region in the center of the rat hypothalamus resulted in the rats increasing their food intake and becoming obese. Damage to the lateral hypothalamus, however, led to decreased food intake and the rats became thin. In both cases the rats eventually reached a new equilibrium body weight; thus it appeared that a capacity for regulation remained, but the set point was altered.

We now know that another region of the hypothalamus, the arcuate nucleus, plays an important role in integrating a variety of feedback signals that influence food intake and body mass. Cells within the arcuate nucleus send axons to the ventromedial and dorsal hypothalamus, as well as to other brain areas that influence food intake and metabolism. One group of arcuate neurons projects to brain areas that inhibit food intake, while the other projects to brain areas that stimulate food intake. But what stimulates or inhibits the activity of the arcuate neurons?

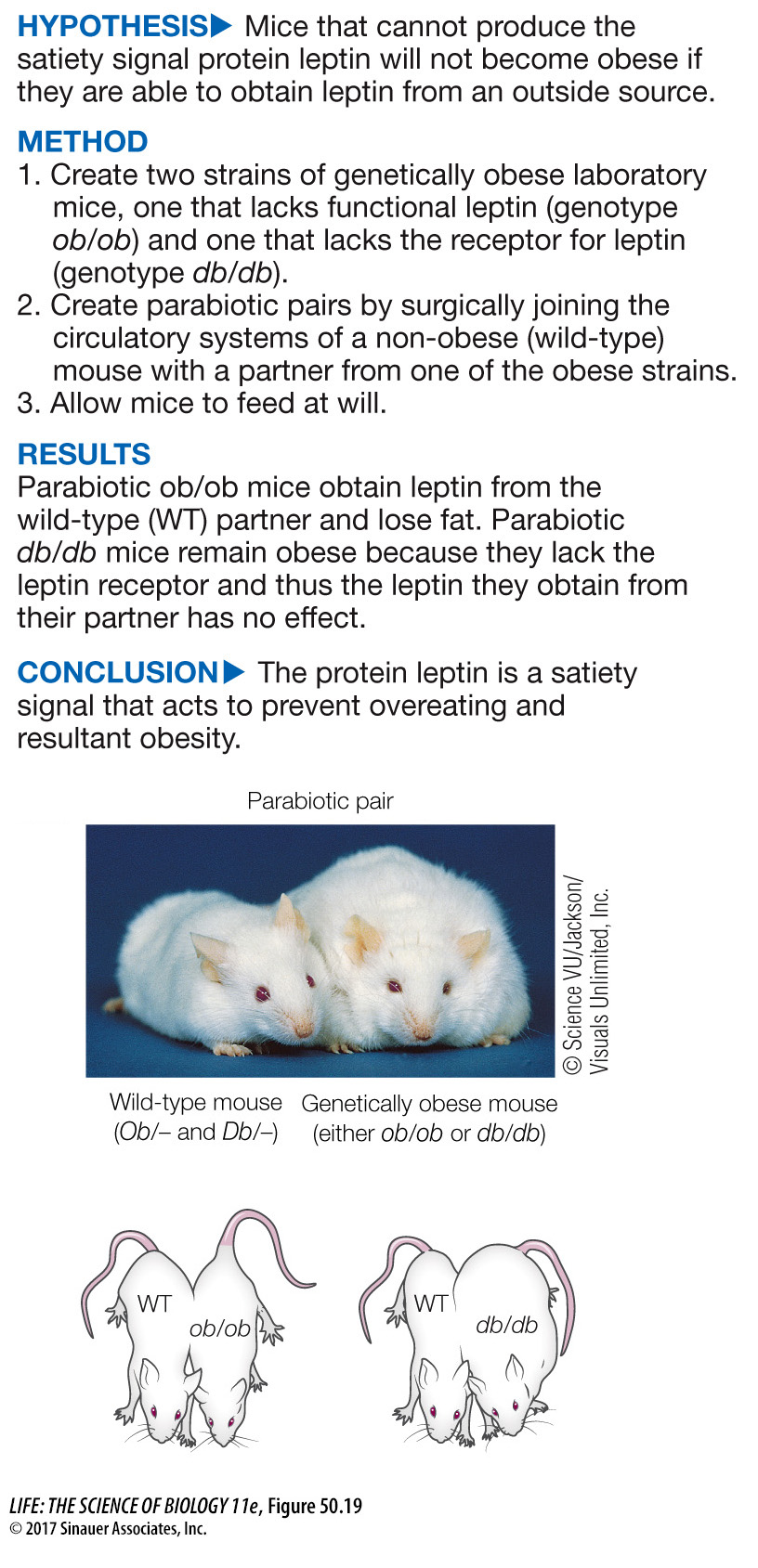

Several factors have been identified that reflect the body’s energy balance. Three of these are the proteins insulin, leptin, and ghrelin. Insulin, as detailed earlier, is released when blood glucose levels are high, and it induces a decline in food intake. Leptin (Greek leptos, “thin”) is released by fat cells in proportion to how much lipid they contain. Evidence that leptin is a satiety signal is described in Figure 50.19. Ghrelin is released by the stomach when it is empty; its levels rise before meals and fall after meals. In the arcuate nucleus, insulin and leptin activate the neurons that inhibit feeding and inhibit the neurons that stimulate feeding. Ghrelin has the opposite effect on these two groups of neurons.

experiment

Figure 50.19 A Single-

Original Papers: Coleman, D. L. 1973. Effects of parabiosis of obese with diabetes and normal mice. Diabetologia 9: 294–

Coleman, D. L. and K. P. Hummel. 1969. Effects of parabiosis of normal with genetically diabetic mice. American Journal of Physiology 217: 1298–

In mice the Ob gene codes for the protein leptin, a satiety factor that signals the brain when enough food has been consumed. The recessive ob allele is a loss-

Activity 50.5 Parabiotic Mice Simulation

An integrative signal that could be playing a central role in regulation of feeding is the enzyme AMP-