Group living has benefits and costs

Apart from their direct influences on reproductive success, social systems can contribute to survival in many ways, but they can also involve costs. Thus the cost–

An obvious example of a benefit of group living is improved foraging efficiency. By hunting in packs, African wild dogs (see Figure 58.17) employ cooperative strategies that enable them to bring down larger prey than could a single dog. The larger the pack, the greater the hunting success rate. Once the prey is killed, the presence of conspecifics also reduces the risk that the wild dogs will lose their prey to larger scavengers, such as hyenas.

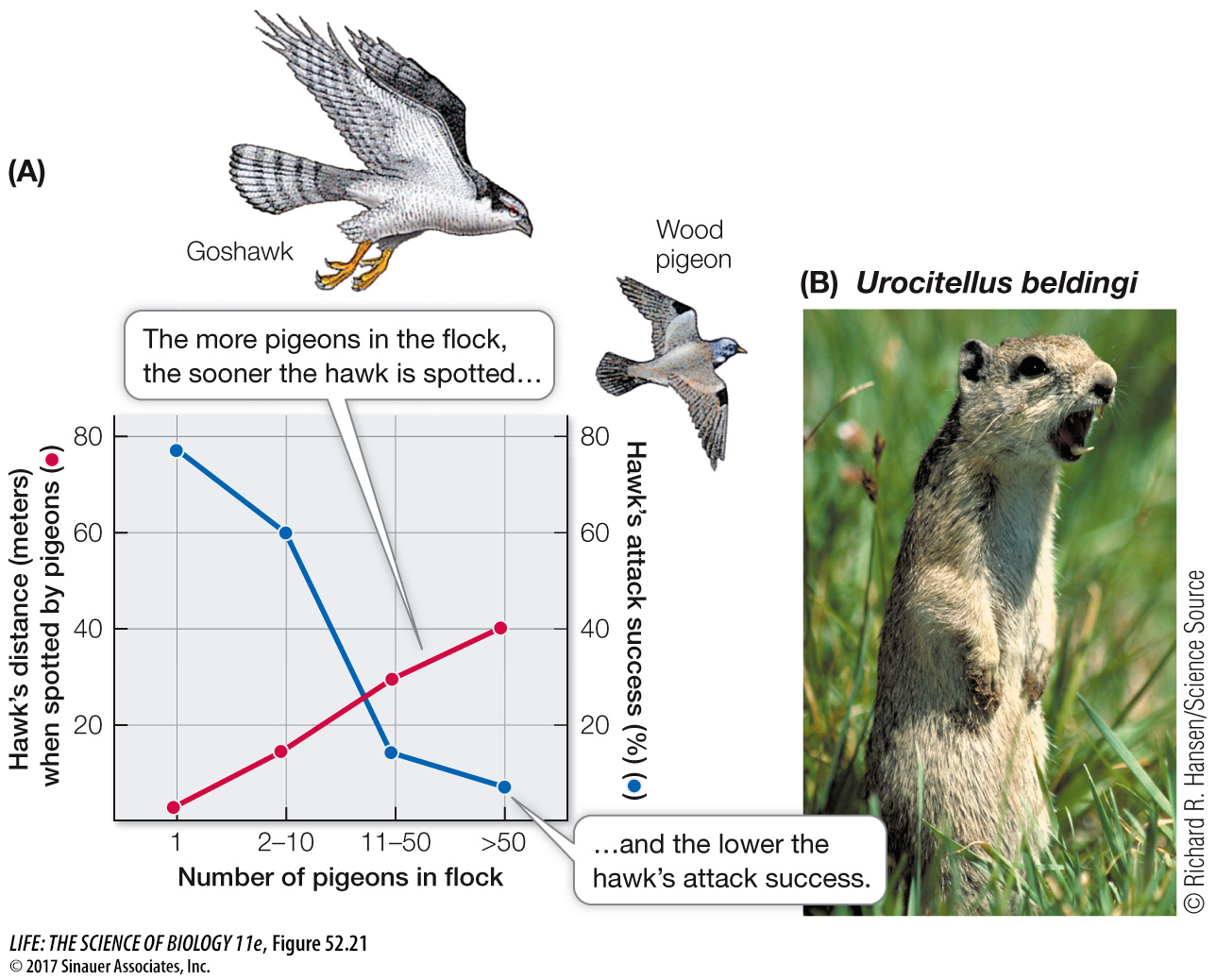

Living in a group can also reduce the risk of individuals becoming prey themselves. Many small birds forage in flocks. To test the hypothesis that flocking provides protection against predators, R. E. Kenward released a trained goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) near wild common wood-

Alarm calling is another means of reducing predation risk, but the caller incurs a risk cost by calling attention to itself. Belding’s ground squirrels (Urocitellus beldingi) live in large colonies in open meadows. When one squirrel announces the presence of a predator with loud, sharp barks, all the nearby squirrels dive into their burrows (Figure 52.21B). Paul Sherman of Cornell University showed that callers double their risk of being preyed on—

Social behavior has many costs as well as benefits. Foraging in a group may reduce the amount of food available to each individual, and the foraging individuals may interfere with one another’s foraging activities. Individuals living in groups may face more competition for mates, as well as for food, than solitary individuals would. A large group may actually attract the attention of predators. And living at high population densities can increase the risk of disease transmission. The study of disease transmission in wild animal populations is a relatively new field, but such studies have made it apparent that species living in social groups are more prone to outbreaks of disease than are solitary species.