Indirect interactions are important to community structure

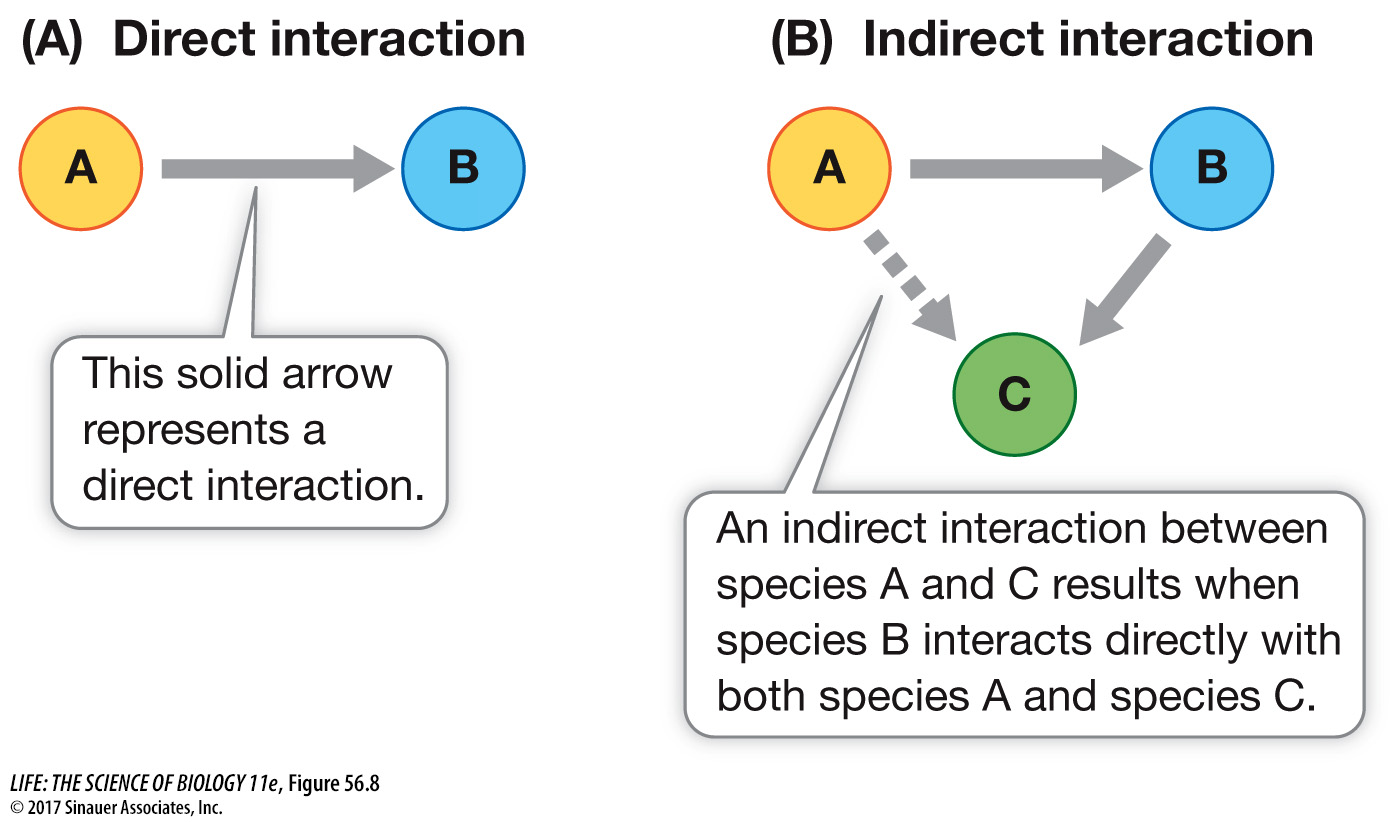

A direct interaction is one that occurs between just two species. Indirect interactions occur when the direct relationships between two species are mediated by a third (or more) species (Figure 56.8). The addition of a third species to a two-

Indirect interactions were observed by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species (1859). Having described the role of bees in flower pollination and seed production of plants in the region of England where he lived, Darwin hypothesized that the number of bees in the region was dependent on the number of field mice that prey on their combs and nests. Noting that mice, in turn, are eaten by cats, Darwin wrote, “Hence it is quite credible that the presence of a feline animal in large numbers in a district might determine, through the intervention first of mice and then of bees, the frequency of certain flowers in that district!”

Today the term “trophic cascade” would be applied to Darwin’s observations. A trophic cascade occurs when the rate of consumption at one trophic level results in a change in species abundance or composition at lower trophic levels. For example, a carnivore eats an herbivore (a direct interaction) and decreases its abundance, causing an indirect positive effect on the primary producer eaten by the herbivore. One example of a trophic cascade is the indirect regulation of U.S. Rocky Mountain meadow and forest communities by wolves, which were reintroduced into Lamar Valley in Yellowstone National Park in 1995. William Ripple and his colleagues at Oregon State University have studied this system extensively.

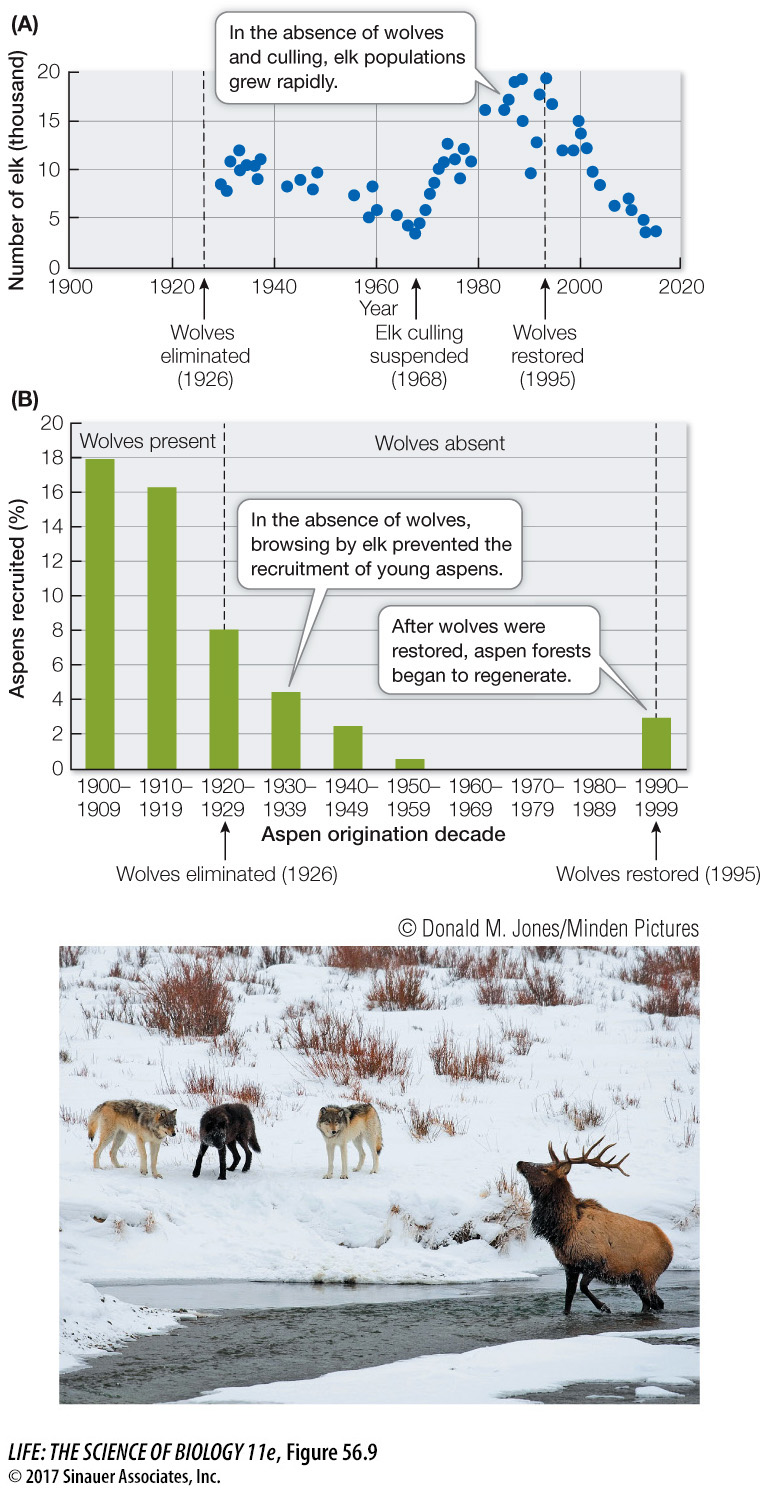

The simplified food web in Yellowstone National Park depicted in Figure 56.3 shows that gray wolves in the park feed on elk, bison, and coyotes. Although they share some of these prey species with coyotes and grizzly bears, wolves exert particularly strong effects on the structure and dynamics of the community. We know this mostly because of how differently the community was structured in their absence, after wolves were hunted to extinction in Yellowstone in 1926. In the absence of wolves, the park service culled elk herds to prevent their populations from exploding. In 1968, in response to public pressure, the selective killing was stopped and the elk population rapidly increased (Figure 56.9A). The elk browsed aspen trees so intensely that the number of young trees recruited (added to the population) declined precipitously; once elk culling stopped, no new trees were recruited at all (Figure 56.9B). The elk also severely browsed streamside willows, with the result that beavers, which depend on willows for food, were mostly gone from Lamar Valley. In regions of the park where elk were absent, however, aspen and willow trees flourished. This observation suggested that the decline of the trees in Lamar Valley was indeed due to elk browsing rather than to climate conditions or other factors.

Media Clip 56.2 How Wolves Change Rivers

In 1995, after wolves had been absent for 70 years, park managers reintroduced them to Yellowstone, and their population grew rapidly. The wolves preyed primarily on elk. The elk population of Lamar Valley dropped, and elk avoided the aspen groves, where they were especially vulnerable to wolf predation. Young aspen began to grow, willows regrew along streams, and the number of beaver colonies increased from one in 1996 to seven in 2003. Thus the presence or absence of a single predator influenced not only populations of its prey but also, indirectly, its prey’s food resource and other species that depended on that resource. It is clear that wolves have a dramatic effect on the structure of meadow and forest communities through the trophic cascade they create.