Overharvesting has driven many species to extinction and changed food webs

Overharvesting occurs when single species, or groups of similar species, are harvested for human use. Overharvesting for such resources as food, clothing, ornamentation, pets, and medicines was once the most important and rapid cause of species extinction. For example, it has been estimated that overharvesting is responsible for roughly 40 percent of the approximately 150 bird species that have become extinct since the 1500s. Maybe one of the most egregious examples of overharvesting of birds came from “plume hunting” in the late nineteenth century. Feathers were harvested for ornamentation on hats and clothing—

Even today, overharvesting is still of great concern for critically endangered species that are not yet extinct but have a high probability of becoming so within the century, particularly as their habitat declines or is further degraded. Recently there has been an alarming uptick in illegal poaching of what might be considered charismatic megafauna, or species with widespread popular appeal. One example is the illegal poaching of elephants and rhinoceroses in much of Africa and Asia because of markets for ivory tusks and horns. A recent study estimated that in central Africa alone, regional elephant population sizes have declined by 64 percent because of illegal killing within the last decade (Figure 58.7). On a continental scale, the study showed that between 2010 and 2012, 40,000 elephants were killed illegally, a rate of 8 percent per year.

Massive and lucrative international trade in exotic pets such as birds, non-

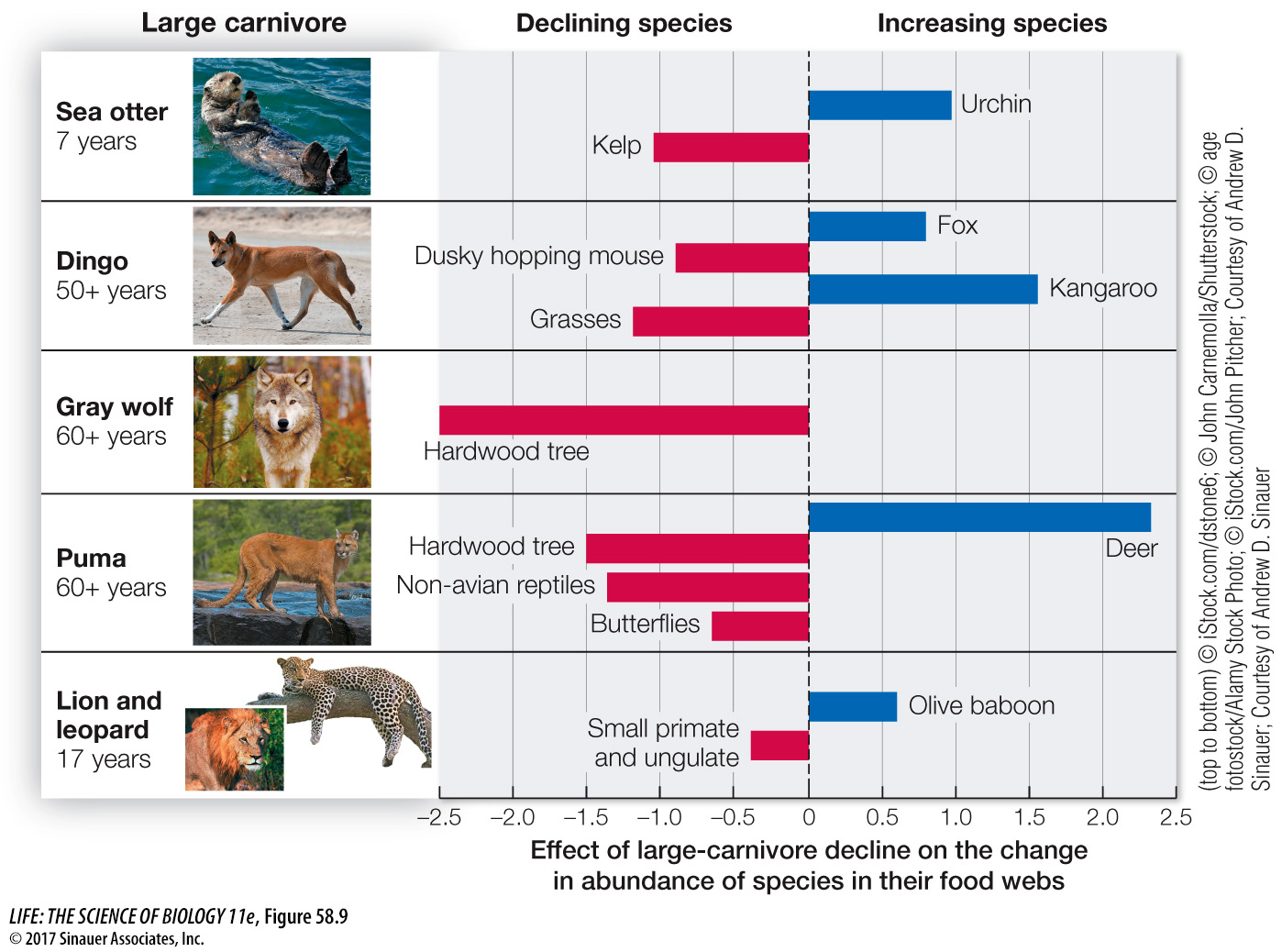

Even though we tend to think of the oceans as boundless, they too are affected by overharvesting. Burgeoning human populations in need of food are placing unprecedented pressure on species harvested from the wild. Humans have fished for at least 40,000 years, but in recent centuries innovations in technology and increasing demand have accelerated overharvesting. A recent comprehensive study of fisheries found that nearly 14 percent of fished taxa collapsed between 1950 and 2007 (Figure 58.8A). The effects of fish harvesting vary widely across the globe, in part because restrictions in some locations have been implemented to encourage the recovery of overfished species (Figure 58.8B). Top predators such as sharks, bluefin tuna, and groupers, which are preferentially harvested, are at particular risk of extinction. These long-

Q: Using the map, indicate which regions of the world are experiencing the highest fisheries exploitation.

The highest fisheries exploitation is occurring off northern Europe in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and off Thailand and Vietnam in the South China Sea. Moderate exploitation is occurring in the northwest Atlantic Ocean off New England and Canada, as well as off the southern tip of Australia.

What are some of the consequences of single-

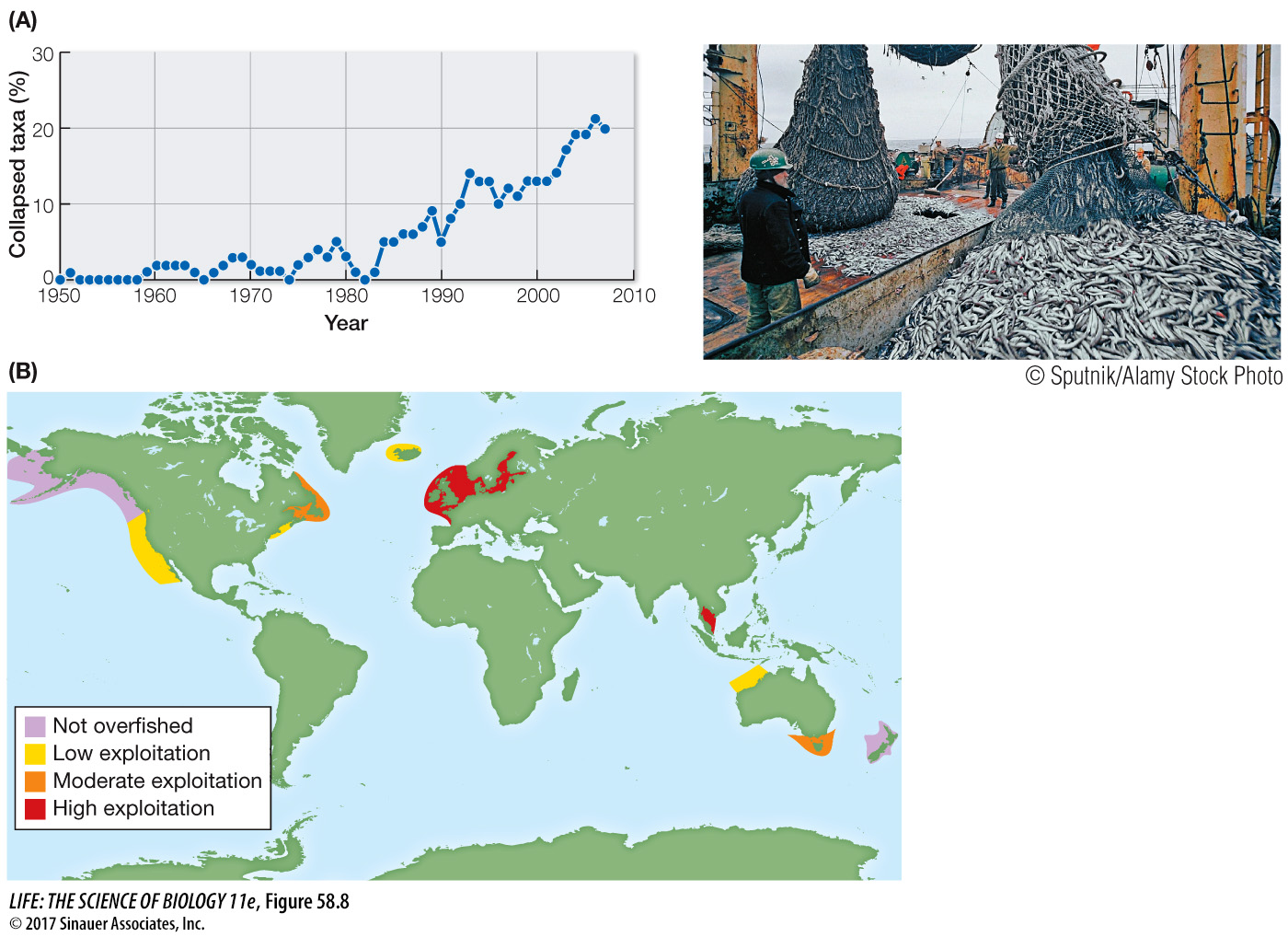

Second, consider what happens when an overharvested species plays an important keystone or foundation role in its community. A recent study by William Ripple and colleagues considered the status and ecological consequences of the decline of 31 of the world’s largest carnivores. Most of the species studied have experienced substantial population declines over the past two centuries as the result of overharvesting, persecution (culling because of conflicts with humans), and habitat loss. Using data from several studies, the researchers showed that when top large carnivores declined, trophic cascades were interrupted, dramatically changing the abundance of herbivore and primary producer species (Figure 58.9). This research suggests that large carnivores are necessary to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem function in some ecosystems.