Degraded ecosystems can be restored

When a species is endangered as a consequence of habitat degradation rather than outright habitat loss, protecting the species may require restoring the habitat to a more natural state. Without human assistance, many degraded ecosystems recover very slowly, if at all. Restoration ecology involves renewing degraded ecosystems by active human intervention. Ideally, restoration involves reestablishing the original structure and function of native ecosystems through such techniques as active removal of pollutants or non-

Recognition of the need for periodic disturbance to maintain healthy ecosystems is a relatively new dimension of conservation biology. We know, for example, that many plant species require periodic fires for successful establishment and survival, but for many years the official policy of the U.S. Forest Service, symbolized by the iconic mascot Smokey Bear, was to suppress all forest fires. Today, however, controlled burning is common, particularly in western North America. In order to use fire as an ecosystem management tool, it is important to know the historical pattern of fires in an area, which can be determined in part by studies of the annual growth rings and fire scars of trees. A schedule of controlled burning that recreates the historical pattern can reduce forest floor litter, avoiding a buildup of fuel that can lead to intense, tree-

Sometimes restoration involves using species that act as ecosystem engineers to help restore the original ecosystem. For example, as Key Concepts 56.3 and Figure 56.12 described, the recolonization of beavers, once hunted to near extinction on Minnesota’s Kabetogama Peninsula, resulted in more wetlands and higher species diversity as a consequence of the beavers’ dam-

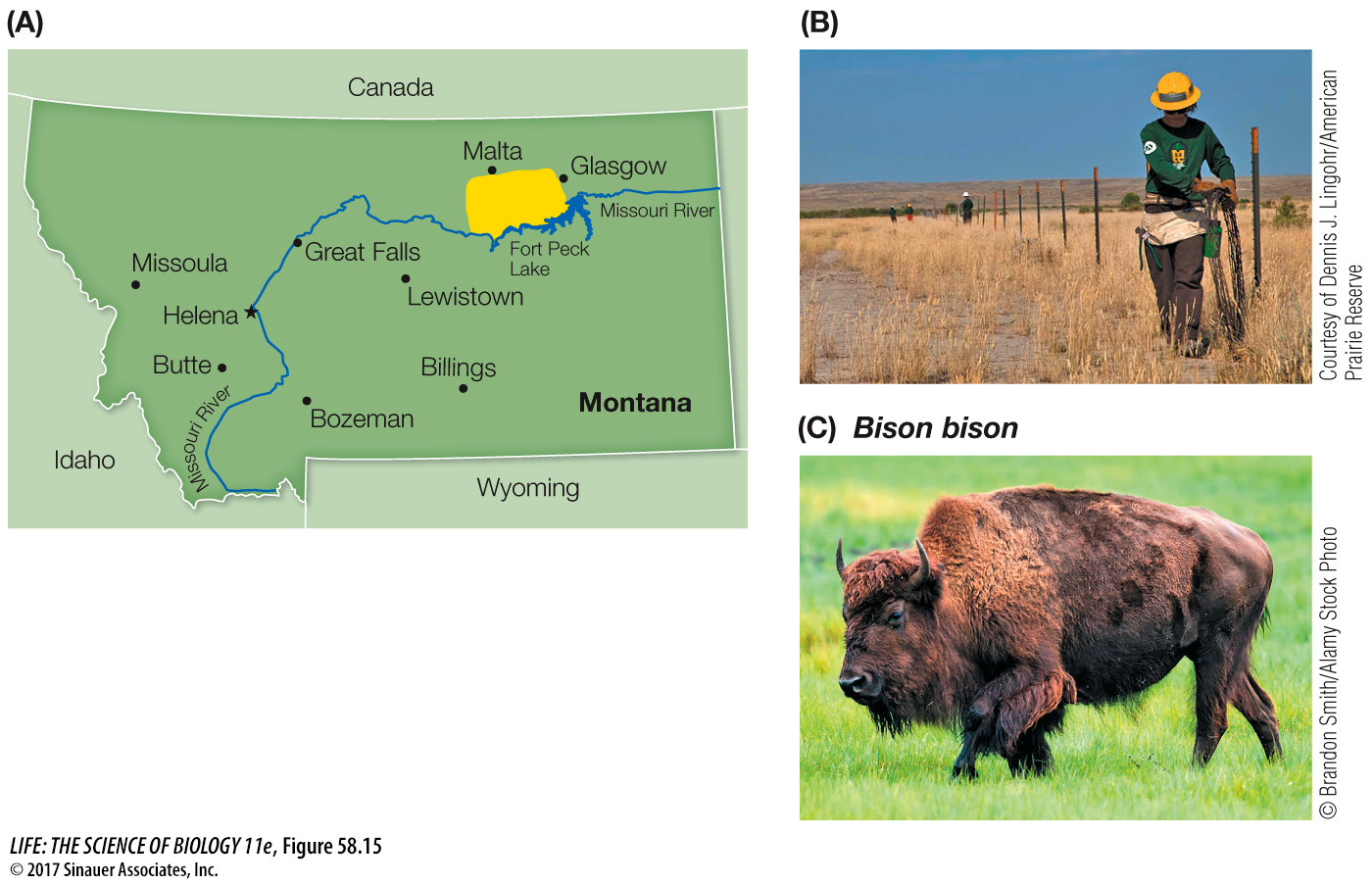

A large-

This ambitious restoration and protection project is feasible for three reasons. First, the private land in the area is owned by a small number of ranchers, each of whom owns extensive grazing leases on public lands administered by either U.S. federal agencies or the State of Montana. Second, most of the land has never been plowed, so native vegetation may recover rapidly when grazing pressures are reduced. Third, the area’s human population is decreasing. Ranchers are aging, and some of their children are leaving for careers in urban settings. Once free-