Step 2: Collect Data

TAKING SAMPLES When biologists gather information about the natural world, they typically collect representative pieces of information, called data or observations. For example, when evaluating the efficacy of a candidate drug for medulloblastoma brain cancer, scientists may test the drug on tens or hundreds of patients, and then draw conclusions about its efficacy for all patients with these tumors. Similarly, scientists studying the relationship between body weight and clutch size (number of eggs) for female spiders of a particular species may examine tens to hundreds of spiders to make their conclusions.

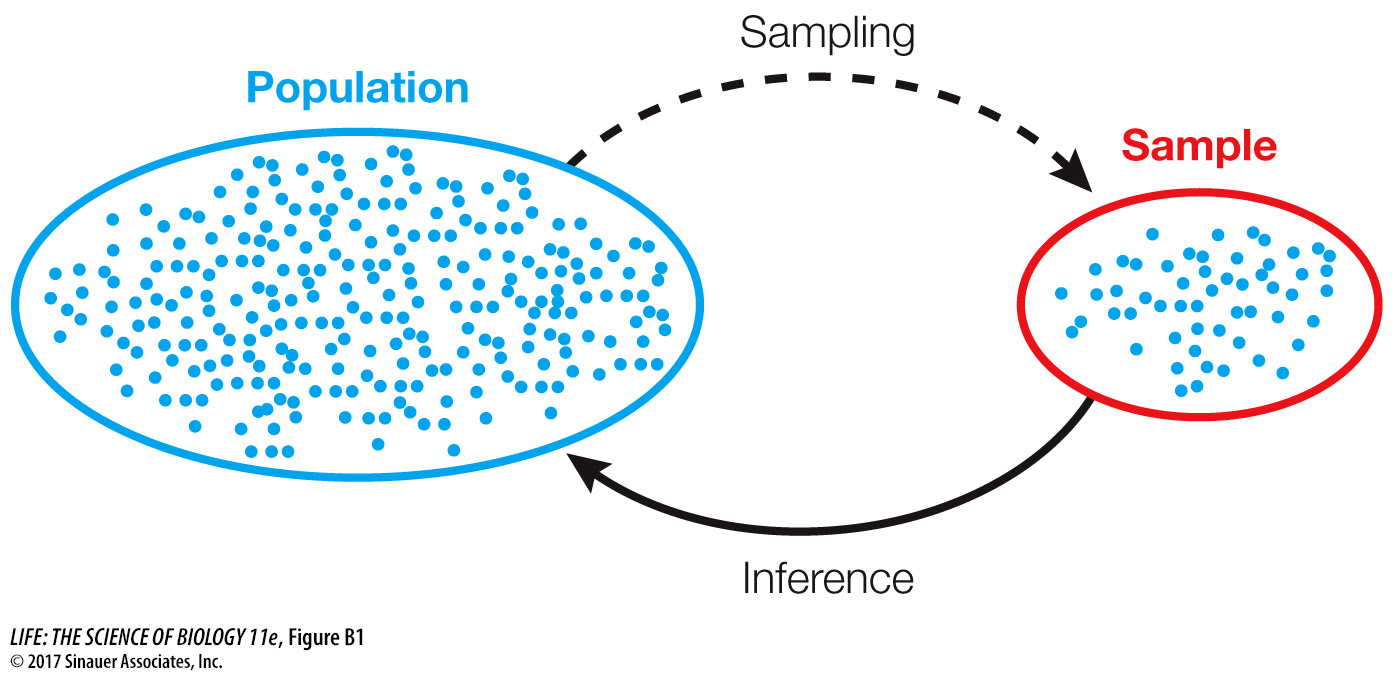

We use the expression “sampling from a population” to describe this general method of taking representative pieces of information from the system under investigation (Figure B1). The pieces of information together make up a sample of the larger system, or population. In the cancer therapy example, each observation was the change in a patient’s tumor size 6 months after initiating treatment, and the population of interest was all individuals with medulloblastoma tumors. In the spider example, each observation was a pair of measurements—

Sampling is a matter of necessity, not laziness. We cannot hope (and would not want) to collect and weigh all of the female spiders of the species of interest on Earth! Instead, we use statistics to determine how many spiders we must collect to confidently infer something about the general population and then use statistics again to make such inferences.

DATA COME IN ALL SHAPES AND SIZES In statistics we use the word “variable” to mean a measurable characteristic of an individual component of a system. Some variables are on a numerical scale, such as the daily high temperature or the clutch size of a spider. We call these quantitative variables. Quantitative variables that take on only whole number values (such as spider clutch size) are called discrete variables, whereas variables that can also take on a fractional value (such as temperature) are called continuous variables.

Other variables take categories as values, such as a human blood type (A, B, AB, or O) or an ant caste (queen, worker, or male). We call these categorical variables. Categorical variables with a natural ordering, such as a final grade in Introductory Biology (A, B, C, D, or F), are called ordinal variables.

Each class of variables comes with its own set of statistical methods. We will introduce a few common methods in this appendix that will help you work on the problems presented in this book, but you should consult a biostatistics textbook for more advanced tests and analyses for other data sets and problems.