Antonio Vivaldi, Violin Concerto in G, La stravaganza, Op. 4, No. 12 (1712–1713)

The undisputed champion of the concerto was the Venetian composer Antonio Vivaldi. Vivaldi wrote hundreds of concertos. He published relatively few of them, in sets of six or twelve; each set was given an opus, or work, number (opus is Latin for “work”). To some opuses he gave titles that evoke the extravagant side of the Baroque dualism (see page 99), such as “Harmonic Whims” (L’estro armonico, Opus 3) and “Extravagance” (La stravaganza, Opus 4). This Concerto in G is the last and one of the best of his Opus 4.

It is a concerto for solo violin. In the age of Antonio Stradivarius, violin maker supreme, a great deal of music was composed at least partly to show off this favorite instrument. The violin’s brilliance was especially prized, as was its ability to play expressively.

The violin soloist is pitted against the basic Baroque orchestra of strings and continuo (see page 108); on our recording the continuo chords are played by a large lute (an archlute). The orchestra is quite small.

First Movement (Spiritoso e non presto) “Spirited, not too fast,” writes Vivaldi at the start of this triple-

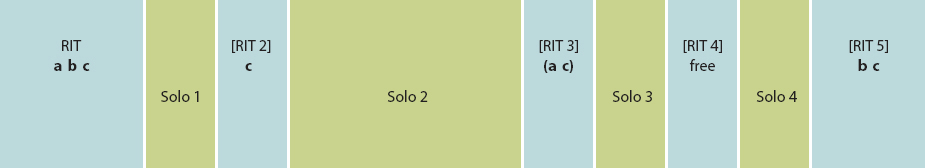

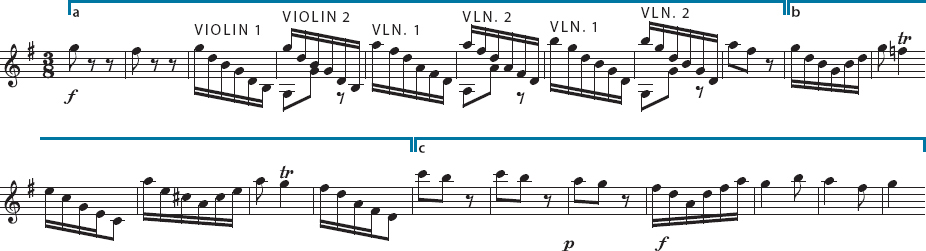

The opening ritornello — with its typical loud, extroverted sound, marked f — consists of three short parts. The first begins with a couple of loud chords to catch the audience’s attention and set the tempo (a); then comes a central section with a distinct sequence (b), and then a cadential section where the dynamic changes to p for a moment (c):

Once the ritornello ends with a very solid cadence (another typical feature of Baroque ritornellos), the solo violin enters, first with music moving at about the same speed as the ritornello, but soon speeding up. Virtuosity for the Baroque violinist meant jumping from the high strings to the low, executing fast scales, in fact any and all kinds of fast playing.

Ritornello 2 is an exact repetition of c from the first ritornello. The second solo has several subsections, which makes it much longer than any of the others; in one section the continuo drops out entirely. Ritornello 3 begins with derivatives of a and c but then wanders off freely and ends in a minor key. This provides a springboard for some expressive playing in the next solo. Ritornello 4 is freer still; it takes just enough from the original ritornello (especially part b) so that it seems to fit in with it and, indeed, to grow out of it spontaneously.

Vivaldi seems to have wanted his first four ritornellos to feel freer and freer, before he finally pulls the piece back in line. After the last solo (following Ritornello 4) cuts in very energetically, he ends the movement with a literal statement of b and c. (Absent is a, perhaps because its attention-