Johann Sebastian Bach, Prelude and Fugue in C Major, from The Well-Tempered Clavier , Book 1 (1722)

The Well-

Some of the fugues give the impression of stern regimentation, some are airy and serene; some echo counterpoint from a century before, others sound like up-

Clavier (or Klavier) is today the German word for piano. In Bach’s time it referred to a variety of keyboard instruments, including the harpsichord and the very earliest pianos (but not including the church organ). The term well-

“The bearer, Monsieur J. C. Dorn, student of music, has requested the undersigned to give him a testimonial as to his knowledge in musicis. . . . As his years increase it may well be expected that with his good native talent he will develop into a quite able musician.”

Joh. Seb. Bach (a tough grader)

Prelude Like the fugues, the preludes in The Well-

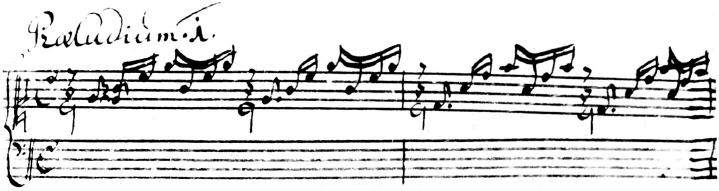

The most famous of them — and also one of the easiest for the novice pianist to work through — is the first, in C major. Its basic gesture is an upward-

Fugue Perhaps because this fugue takes pride of place in The Well-

The subject is introduced in a spacious exposition — soprano, tenor, and bass follow the alto at even time intervals. The subject moves stepwise up the scale in even rhythms at first, only to reverse course with a quick twist downward. Listen carefully for this twist; it will help you pick out the many subject entries to come. (The whole subject is shown in Listening Chart 6.)

After the exposition, however, all bets are off, fugally speaking. Instead of the more usual episodes alternating with orderly entries of the subject, this fugue is all about stretto. The first stretto comes as soon as the exposition is complete, with two voices overlapping, and from then on entries begin to pile up.

But an overall order underlies all these strettos. The fugue comes, exactly at its midpoint, to a strong cadence on a key different from our starting key, and in the minor mode. This articulates but does not stop the action, as the stretto entries of the subject begin again immediately, back in the home key. Indeed, as if to counterbalance the clarity of the cadence, the entries here come faster than anywhere else in the fugue — eight of them in quick succession. At one moment four entries all overlap, the last beginning before the first has finished.

After this frenzy of entries, even a big cadence back in the home key takes a moment to sink in, as three more entries of the subject quickly follow it. The energy of all this finally comes to rest in the soprano voice, which at the very end floats beautifully up to the highest pitch we have heard.