Baroque Dance Form

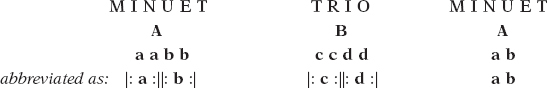

A Baroque dance has two sections, a and b. Each ends with a strong cadence coming to a complete stop, after which the section is immediately repeated. Both sections tend to include the same motives, cadences, and other such musical details, and this makes for a sense of symmetry between them, even though b is nearly always longer than a. Hence Baroque dance form is diagrammed a a b b, abbreviated as |: a:||: b:| where the signs |: and :| indicate that everything between them is to be repeated. This form is also called binary form.

With shorter dances, composers tended to group them in pairs of the same type, with the first coming back after the second, resulting in a large-

Later the idea of contrast between A and B was always kept, with B quieter than A, or perhaps changed in mode. Thus a Baroque minuet and trio, to choose this type as an example, consists of one minuet followed by a second, contrasting minuet, and then the first one returns. This time, however, the repeats in the binary form are usually omitted:

The term trio, to indicate a contrasting, subsidiary section, lasted until well after the Baroque period. Band players know it from the marches of John Philip Sousa and others.