The Lutheran Chorale

The content and structure of Bach’s cantatas varied from one work to the next. But in general they tend to fall into a short series of operatic arias and recitatives with one or more choral movements, like an excerpt from an oratorio. (Most secular cantatas, likewise, resemble a scene or two from an opera.) A special feature of nearly all Lutheran cantatas is their use of traditional congregational hymns. Lutheran hymns are called chorales (co-

Martin Luther, the father of the Protestant Reformation, placed special emphasis on hymn singing by the congregation when he decided on the format of Lutheran services. Two hundred years later, in Bach’s time, a large body of chorales served as the foundation for Lutheran worship, both in church services and also at informal pious devotions in the home. Everybody knew the words and melodies of these chorales. You learned them as a small child and sang them in church all your life. Consequently when composers introduced chorale tunes into cantatas (and other sacred-

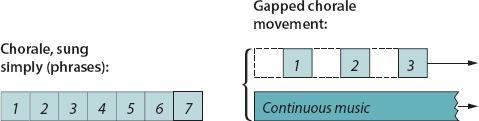

Just how were tunes introduced? There were many ways. The last movement of a Bach cantata is usually a single hymn stanza sung straight through, in much the same simple way as the congregation would sing it, but with the orchestra playing and a homophonic harmonization of the melody added.

Longer cantata movements present the individual lines or phrases of the chorale one by one, with gaps in between them. Newly composed music by Bach runs on continuously, both during the chorale phrases (that is, in counterpoint with them) and during the gaps. In such a gapped chorale, the chorale melody is delivered in spurts. It can be sung, or it can be played by one prominent instrument — an oboe, say, or a trumpet — while the continuous music goes along in the other instruments and/or voices.