Rhythm

Perhaps the most striking change in music between the Baroque and Classical periods came in rhythm. In this area the artistic ideal of “pleasing variety” reigned supreme. The unvarying rhythms of Baroque music came to be regarded as obvious and boring.

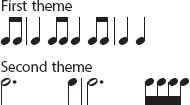

Classical music is highly flexible in rhythm. Throughout a single movement, the tempo and meter remain constant, but the rhythms of the various themes tend to differ in both obvious and subtle ways. In the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony in G Minor, for example, the first theme moves almost entirely in eighth notes and quarters, whereas the second theme is marked by longer notes and shorter ones — dotted half notes and sixteenths.

Audiences wanted variety in music; composers responded by refining the rhythmic differences between themes and other musical sections, so that the differences sound like more than differences — they sound like real contrasts. The music may gradually increase or decrease its rhythmic energy, stop suddenly, press forward by fits and starts, or glide by smoothly. All this gives the sense that Classical music is moving in a less predictable, more interesting, and often more exciting way than Baroque music does.