Texture: Homophony

The predominant texture of Classical music is homophonic. In Classical compositions, melodies are regularly heard with a straightforward harmonic accompaniment in chords, without counterpoint and without even a melodic-

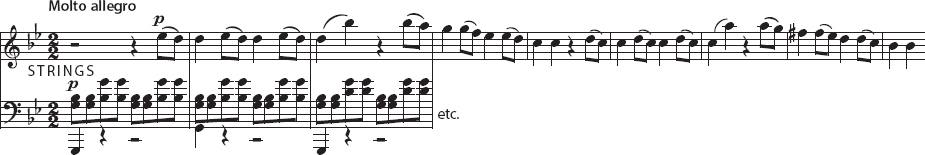

All this made, and still makes, for easy listening. The opening of Mozart’s famous Symphony No. 40 in G Minor proclaims the new sonorous world of the late eighteenth century:

A single quiet chord regrouped and repeated by the violas, the plainest sort of bass support below, and above them all a plaintive melody in the violins — this simple, sharply polarized texture becomes typical of the new style.

Homophony or melody with harmony was not, however, merely a negative reaction to what people of the time saw as the heavy, pedantic complexities of Baroque counterpoint. It was also a positive move in the direction of sensitivity. When composers found that they were not always occupied in fitting contrapuntal parts to their melodies, they also discovered that they could handle other elements of music with more “pleasing variety.” In particular, a new sensitivity developed to harmony for its own sake.

One aspect of this development was a desire to specify harmonies more precisely than in the Baroque era. The first thing to go was the continuo, which had spread its unspecified (because improvised) chord patterns over nearly all Baroque music. Classical composers, newly alert to the sonorous quality of a particular chord, wanted it spaced and distributed among various instruments just so. They refused to allow a continuo player to obscure the chord with unpredictable extra notes and rhythms.

It may seem paradoxical, then, but the thrust toward simplicity in texture and melody led through the back door to increased subtlety in other areas, especially in rhythm and in harmony.