Biography

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Mozart was born in Salzburg, a picturesque town in central Austria, which today is famous for its music festivals. His father, Leopold, was a court musician and composer who also wrote an important book on violin playing. Mozart showed extraordinary talent at a very early age. He and his older sister, Nannerl, were trotted all over Europe as child prodigies; between the ages of six and seventeen, Wolfgang never spent more than ten successive months at home. His first symphony was played at a London concert when he was only eight years old.

But mostly Wolfgang was displayed at courts and salons, and in a somewhat depressing way this whole period of his career symbolizes the frivolous love of entertainment that reigned at midcentury. The future queen Marie Antoinette of France was one of those for whose amusement the six-

It was much harder for Mozart to make his way as a young adult musician. As usual in those days, he followed in his father’s footsteps as a musician at the court of Salzburg, which was ruled by an archbishop. (Incidentally, one of their colleagues was Joseph Haydn’s brother Michael.) But the archbishop was a disagreeable autocrat with no patience for independent-

It seems clear that another reason for Mozart’s move was to get away from his father, who had masterminded the boy’s career and now seemed to grow more and more possessive as the young man sought his independence. Leopold disapproved of Wolfgang’s marriage around this time to Constanze Weber, a singer. (Mozart had been in love with her older sister, Aloysia — a more famous singer — but she rejected him.)

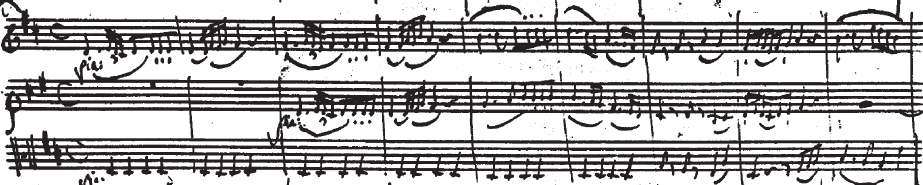

Mozart wrote his greatest operas in Vienna, but only the last of them, The Magic Flute, had the success it deserved. Everyone sensed that he was a genius, but his music seemed too difficult — and he was a somewhat difficult personality. He relied for his living on teaching and on the relatively new institution of concerts. Every year he set up a concert at which he introduced one of his piano concertos. In addition, the program might contain arias, a solo improvisation, and an overture by somebody else.

But as happens with popular musicians today, Mozart seems (for some unknown reason) to have suddenly dropped out of fashion. After 1787, his life was a struggle, though he did receive a minor court appointment and the promise of a church position, and finally scored a really solid hit with The Magic Flute. When it seemed that financially he was finally getting out of the woods, he died suddenly at the age of thirty-

He died under somewhat macabre circumstances. He was composing a Requiem Mass, that is, a Mass for the Dead, commissioned by a patron who insisted on remaining anonymous. Mozart became ill and began to think he was writing for his own demise. When he died, the Requiem still unfinished, a rumor started that he had been poisoned by the rival composer Antonio Salieri.

Unlike Haydn, the other great master of the Viennese Classical style, Mozart allowed a note of disquiet, even passion, to emerge in some of his compositions (such as the Symphony in G Minor). The Romantics correctly perceived this as a forecast of their own work. Once we recognize this, it is hard not to sense something enigmatic beneath the intelligence, wit, and sheer beauty of all Mozart’s music.

Chief Works: The comic operas The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte (That’s What They All Do), and The Magic Flute ◼ Idomeneo, an opera seria ◼ Church music: many Masses, and a Requiem (Mass for the Dead) left unfinished at his death ◼ 41 symphonies, including the Prague, the G minor, and the Jupiter ◼ String quartets and quintets ◼ Concertos for various instruments, including nearly thirty much-

Encore: After Symphony No. 40, listen to the Clarinet Quintet and The Marriage of Figaro (Act I).

Image credit: Ali Meyer/CORBIS.