Franz Joseph Haydn, Symphony No. 94 in G (“The Surprise,” 1791)

The second movement of a symphony is the slow movement, a restful episode to contrast with the vigorous first movement. There is no standardized form for slow movements, either in symphonies or in other genres, such as sonatas or concertos. Mozart, in his late symphonies, preferred sonata form or some derivative of it. Haydn favored his own version of variation form, and indeed tuneful and witty variations movements in symphonies were a specialty of his. One of his most beloved variations movements is the Andante from his Symphony No. 94, nicknamed “The Surprise” Symphony.

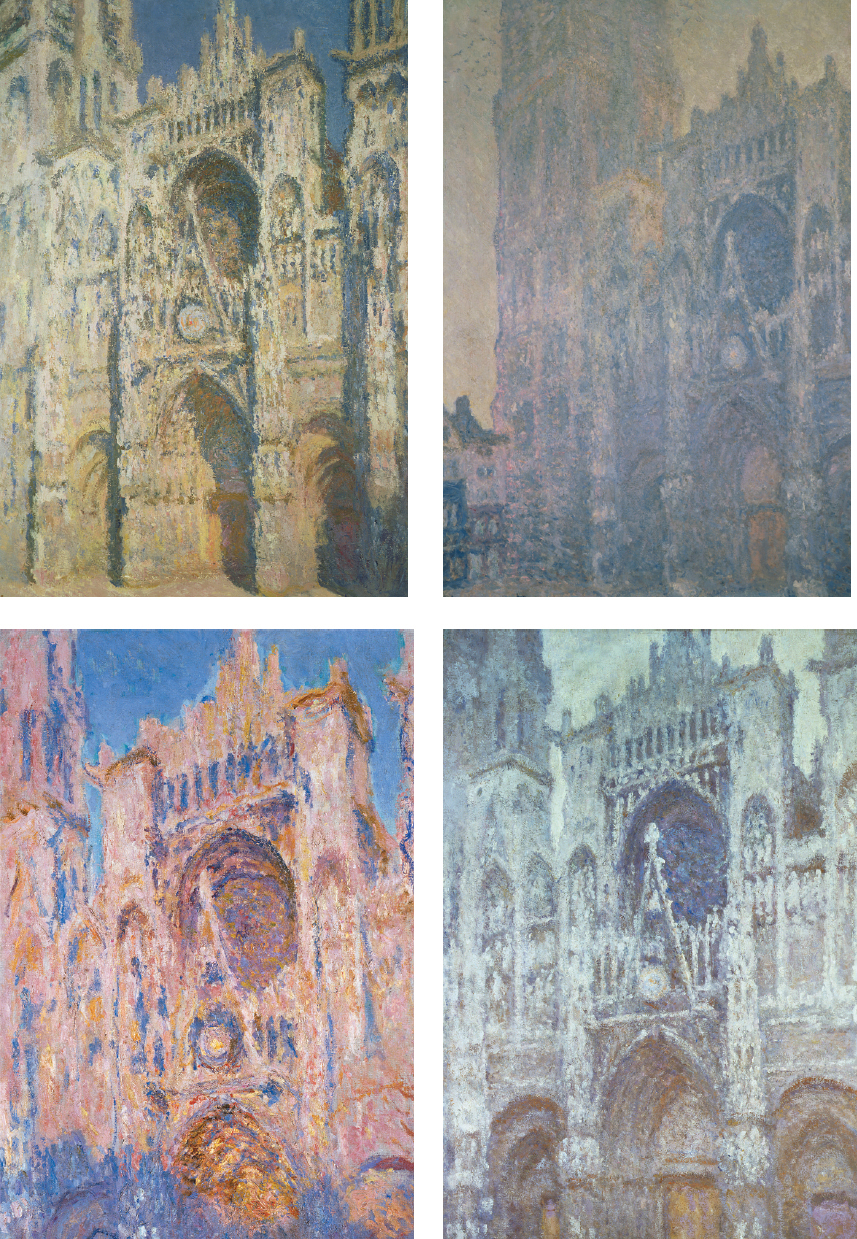

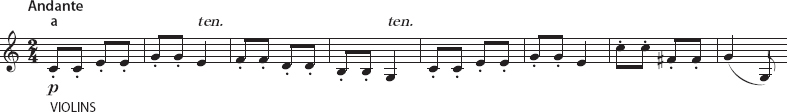

For the theme of this movement Haydn devised a tune as charming as it is simple:

It is presented at the beginning almost in the |: a :||: b :| form we might expect, except that Haydn alters each repetition slightly. The repeat of the b phrase adds flutes, oboes, and horns not present the first time through, while the second a phrase is played more quietly than the first until its final chord — a crashing fortissimo stroke that gave the symphony its nickname.

Basic Variation

| THEME | |: a :| | |: b :| |

| Variation 1 | |: a1:| | |: b1:| |

| Variation 2 | |: a2:| | |: b2:| |

| Variation 3 | |: a3:| | |: b3:| |

Now the variations start — four in all, plus a brief coda — and in each of them the original theme can be clearly heard, while much else is varied. The normal expectation would be the basic scheme shown in the margin, as discussed on page 169. Haydn wrote dozens of variations movements in this “standard” form — though not, interestingly, in symphonies. He seems to have felt it would be boring for a concert audience and that he needed to do something freer. Instead of repeating a and b phrases in the variations exactly, he might write variations within variations, as indicated by prime marks in the following diagram:

| Theme | a | a | b | b |

| “Normal” variation | a1 | a1 | b1 | b1 |

| Variation within variation | a1 | a1′ | b1 | b1′ |

Variation 1 in this movement is of the “normal” kind, leading us gently toward the greater changes to come. The lower strings present the theme and its harmonic support, while the first violins, aided for a moment by the flutes, add a graceful new melody above them.

“The admirable and matchless HAYDN! From whose productions I have received more pleasure late in my life, when tired of most Music, than I ever received in the ignorant and rapturous part of my youth.”

English music historian Charles Burney, 1776

Variation 2 sets a different tone entirely, as it shifts to the minor mode and presents the first phrase of the theme ff. This phrase, a2, then modulates off to end in a new key — and back in the major mode. (Classical composers tended not to linger for long in the minor mode in their variations movements.) Phrase a2 is literally repeated, leading us to think we are about to embark on the b2 phrases of a normal variation. Haydn has other plans, however; instead of |: b2 :|, we get loud, tumultuous music, with the opening motive from the theme developed in the lower strings. This works its way to a sense of harmonic expectancy and a pause, leaving only the first violins. It is as if Haydn momentarily shifted to sonata form and wrote a miniature development section, complete with retransition.

The violins lead us smoothly to Variation 3, a variation within a variation. For a3 the theme, back in the major mode, is presented in quicker rhythms by a solo oboe. The next phrase, a3′, offers a duet of flute and oboe high above the theme in the strings. This arrangement continues through b3 and b3′, with quiet French horns added in b3′.

Variation 4 begins triumphantly with the complete orchestra, including trumpets and drums; the winds present the theme while the violins play a quick countermelody, all ff. But this is another variation within a variation, and Haydn quiets the jubilant mood abruptly in a4′ and b4, played mainly by the strings, before restoring it in b4′.

The return of the triumphant mood seems to signal the end of the movement, and indeed it leads straight into a brief coda. For this Haydn reserves one more surprise — a bigger one, even, than the crashing chord at the beginning that gave the symphony its nickname. The last, incomplete statement of the theme grows softer and softer, over mysterious and dissonant harmonies that seem to recall the minor-