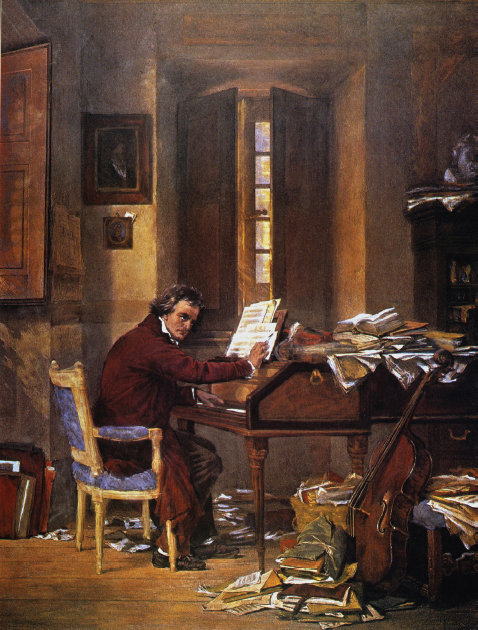

3 | Beethoven’s “Third Period”

Beethoven’s music is traditionally divided into three style periods. The first period (until 1800, in round numbers) covers music building on the style of Haydn and Mozart. The middle period contains characteristically “heroic” works like the Eroica and Fifth symphonies.

In the third period (from around 1818 to 1827) Beethoven’s music loses much of its earlier tone of heroism. It becomes more introspective and tends to come framed in more intimate genres than the symphony, such as the piano sonata, the string quartet, and the piano miniature (a new genre that looks to the future; see page 229). The strength of his earlier music seems to be tempered by a new gentleness and spirituality. (However, Beethoven’s mightiest symphony, the Ninth, also dates from this period.)

Beethoven’s late music also becomes more abstract — a difficult quality to specify. In part the abstractness involves his free exploration of cerebral formal designs, such as long fugues looking back on Bach, or variation forms that range farther from their themes than any before them. In part it is a matter of the themes themselves, which are reduced to fragments or to elemental musical materials: scales, quick-