Grandiose Compositions

Another Romantic tendency was diametrically opposed to the miniatures. Many composers wrote what may be called grandiose compositions — larger and larger symphonies, cantatas, and so on, with more and more movements, increased performing forces, and a longer (sometimes much longer) total time span. For example, Hector Berlioz’s symphony Romeo and Juliet of 1839 lasts for nearly an hour and a half. (A typical Haydn symphony lasts twenty minutes.) Starting with an augmented symphony orchestra, Berlioz added soloists and a chorus in certain of the movements and a narrator between them, and then threw in an off-

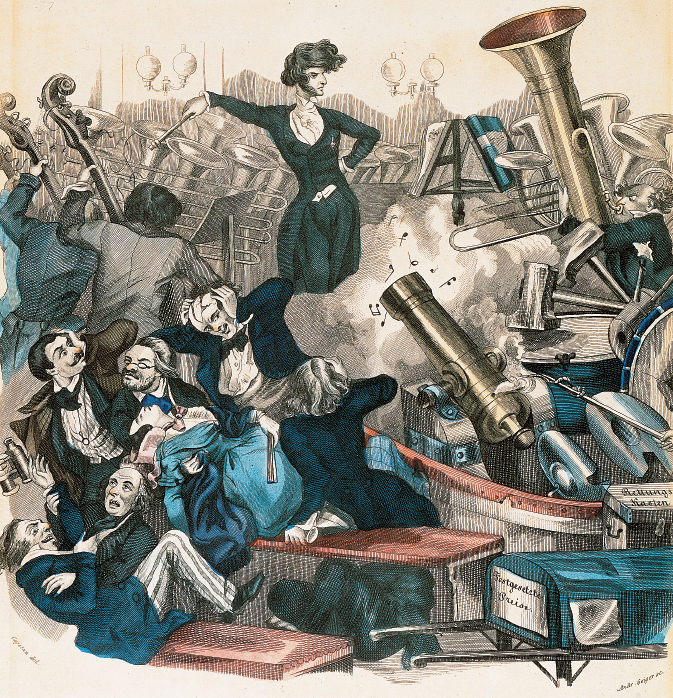

The total effect of these grandiose compositions involved not only music but also poetry, philosophical or religious ideas, story lines, and (in operas) dramatic action. Listeners were impressed, even stupefied, by a combination of opulent sounds, great thoughts, powerful emotions, and sheer length.

These works met what we have called the problem of musical form in their own way. The bigger the work, the bigger the problem, but to help solve it composers could draw on extramusical factors — on the words of a vocal work, or the program of an instrumental one. Music could add emotional conviction to ideas or stories; in return these extramusical factors could supply a rhyme and reason for the sequence of musical events — that is, for the musical form.