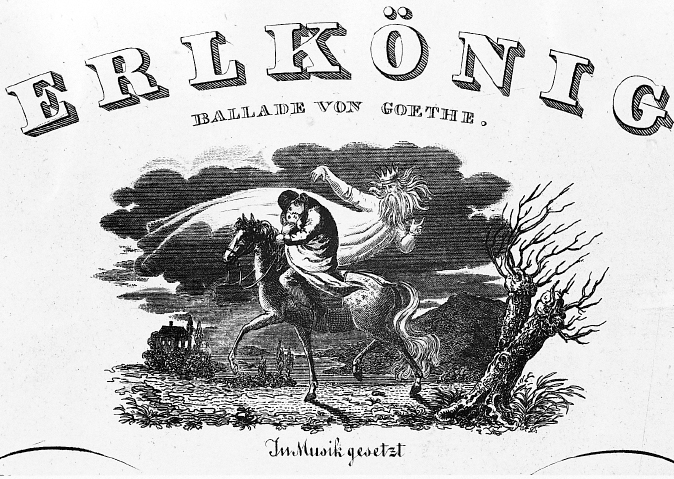

Franz Schubert, “Erlkönig” (The Erlking) (1815)

The earliest and (for most musicians) greatest master of the lied is Franz Schubert. He wrote close to seven hundred songs in his short lifetime. In his eighteenth year, 1815, he averaged better than a song every two days! Many of these are quite short tunes with simple piano accompaniments, but Schubert’s tunes are like nobody else’s; he was a wonderfully spontaneous melodist. Later in life his melodies became richer but no less beautiful, and taken together with their poems, the songs often show remarkable psychological penetration.

One of those songs from 1815 was an instant hit: “Erlkönig” (The Erlking), published as the composer’s opus 1, and still today Schubert’s best-

The poem is by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the greatest literary figure of the day — by turns a Romantic and a Classical poet, novelist, playwright, naturalist, and philosopher, and a favorite source of texts for many generations of lied composers. Cast in the old storytelling ballad form, which enjoyed a vogue in the Romantic era, and dealing with death and the supernatural, the poem is famous in its own right.

Though Goethe’s poem consists of eight parallel stanzas, they are not set to the same music. Schubert provided the later stanzas with different or modified music; such a song is said to be through-

The opening piano introduction sets the mood of dark, tense excitement. The right hand hammers away at harsh repeated notes in triplets, representing the horse’s hooves, while the left hand has an agitated motive:

Schubert invented different music for the poem’s three characters (and also the narrator). Each “voice” characterizes the speaker in contrast to the others. The father is low, stiff, and gruff, the boy high and frantic. Marked ppp, and inaudible to the father, the ominously quiet and sweet little tunes crooned by the Erlking, offering his “schöne Spiele” — lovely games — add a chilling note.

Two things help hold this long song together. First, the piano’s triplet rhythm continues ceaselessly, until the very last line, where recitative style lets us know that the ride is over. (The triplets are muffled during the Erlking’s speeches — because the child is hearing him in a feverish daze?) Second, there are some telling musical repetitions: the agitated riding motive (stanzas 1–

LISTEN

Schubert, “Erlkönig”

| 0:23 |

Wer reitet so spät, durch Nacht und Wind? Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind; Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm, Er fasst ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm. |

Who rides so late through the night and wind? It is the father with his child. He holds the youngster tight in his arm, Grasps him securely, keeps him warm. |

| 0:56 |

“Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?” “Siehst, Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht? Den Erlenkönig mit Kron’ und Schweif?” “Mein Sohn, est ist ein Nebelstreif.” |

“My son, what makes you afraid to look?” “Don’t you see, Father, the Erlking there? The King of the forest with his crown and train?” “Son, it’s only a streak of mist.” |

| 1:29 |

“Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir! Gar schöne Spiele spiel’ ich mit dir; Manch’ bunte Blumen sind an dem Strand; Meine Mutter hat manch’ gülden Gewand.” |

“Darling child, come away with me! I will play some lovely games with you; Many bright flowers grow by the shore; My mother has many golden robes.” |

| 1:52 |

“Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht Was Erlenkönig mir leise verspricht?” “Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind: In dürren Blättern säuselt der Wind.” |

“Father, Father, do you not hear What the Erlking is softly promising me?” “Calm yourself, be calm, my son: The dry leaves are rustling in the wind.” |

| 2:14 |

“Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn? Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön; Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.” |

“Well, you fine boy, won’t you come with me? My daughters are ready to wait on you. My daughters lead the nightly round, They will rock you, dance for you, sing you to sleep!” |

| 2:32 |

“Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort Erlkönigs Töchter am düstern Ort?” “Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich seh es genau: Es scheinen die alten Weiden so grau.” |

“Father, Father, do you not see The Erlking’s daughters there in the dark?” “My son, my son, I see only too well: It is the gray gleam in the old willow trees.” |

| 3:01 |

“Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt, Und bist du nicht willig, so brauch’ ich Gewalt.” “Mein Vater, mein Vater, jetzt fasst er mich an! Erlkönig hat mir ein Leids getan!” |

“I love you, your beauty allures me, And if you’re not willing, then I shall use force.” “Father, Father, he is seizing me now! The Erlking has hurt me!” |

| 3:26 |

Dem Vater grauset’s, er reitet geschwind, Er hält in Armen das ächzende Kind, Erreicht den Hof mit Müh und Not; In seinen Armen das Kind war tot. |

Fear grips the father, he rides like the wind, He holds in his arms the moaning child; He reaches the house hard put, worn out; In his arms the child was — dead! |