Robert Schumann, Dichterliebe (A Poet’s Love) (1840)

LISTEN

“To cast light into the depths of the human heart — the artist’s mission!”

Robert Schumann

“Schubert died. Cried all night,” wrote the eighteen-

Then in 1840, the year of his marriage, he suddenly started pouring out lieder. Given this history, it is not surprising that in Schumann’s songs the piano is given a more complex role than in Schubert’s. This is particularly true of his most famous song cycle, Dichterliebe, the first and last songs of which (nos. 1 and 16) we will examine here. Dichterliebe has no real story; its series of love poems traces a psychological progression from cautious optimism to disillusionment and despair. They are the work of another great German poet, Heinrich Heine, a man who reacted with bitter irony against Romanticism, while acknowledging his own hopeless commitment to its ideals.

“Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” (In the wonderfully lovely month of May) The song begins with a piano introduction, halting and ruminative — which seems at first to be a curious response to the “wonderfully lovely” month of May. The piano part winds its way in and out of the vocal line, ebbing and flowing rhythmically and sometimes dwelling on quiet but piercing dissonant harmonies.

What Schumann noticed was the hint of unrequited longing in Heine’s very last line, and he ended the song with the piano part hanging in midair, without a true cadence, as though in a state of reaching or yearning: a truly Romantic effect. Technically, the last sound is a dissonance that requires resolution into a consonance (see page 28) but does not get it (until the next song).

In this song, both stanzas of the poem are set to identical music. As mentioned earlier, such a song is called strophic; strophic setting is of course familiar from folk songs, hymns, popular songs, and many other kinds of music. For Schumann, this kind of setting had the advantage of underlining the similarity in the text of the song’s two stanzas, both in meaning and in actual words. Certainly his music deepens the tentative, sensitive, hope-

The qualities of intimacy and spontaneity that are so important to Romantic miniatures can be inhibited by studio recording. Our recording of Schumann’s song was made at a concert (you will hear applause as the artists enter).

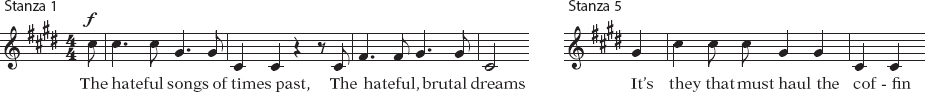

“Die alten, bösen Lieder” (The hateful songs of times past) After many heart-

But there is a sudden reversal of mood in stanza 6, as the poet offers to tell us what this morbid list of funeral arrangements is all about. In the music, first the accompaniment disintegrates and then the rhythm. All the poet’s self-

Instead, in a lovely meditative piano solo, music takes over from words. Not only does the composer interpret the poet’s words with great art, both in the hectic early stanzas and the self-

LISTEN

Schumann, “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai”

| 0:28 |

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai, Als alle Knospen sprangen, Da ist in meinem Herzen Die Liebe aufgegangen. |

In the wonderfully lovely month of May, When all the buds were bursting, Then it was that in my heart Love broke through. |

| 1:05 |

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai, Als alle Vögel sangen, Da hab’ ich ihr gestanden Mein Sehnen und Verlangen. |

In the wonderfully lovely month of May, When all the birds were singing, Then it was I confessed to her My longing and desire. |

LISTEN

Schumann, “Die alten, bösen Lieder”

| 0:05 |

Die alten, bösen Lieder, Die Träume bös’ und arg, Die lasst uns jetzt begraben: Holt einen grossen Sarg. |

The hateful songs of times past, The hateful, brutal dreams, Let’s now have them buried; Fetch up a great coffin. |

| 0:23 |

Hinein leg’ ich gar Manches, Doch sag’ ich noch nicht, was. Der Sarg muss sein noch grösser Wie’s Heidelberger Fass. |

I’ve a lot to put in it — Just what, I won’t yet say; The coffin must be even bigger Than the Great Cask of Heidelberg. |

| 0:41 |

Und holt eine Todtenbahre Und Bretter fest und dick, Auch muss sie sein noch länger Als wie zu Mainz die Brück’. |

And fetch a bier, Boards that are strong and thick; They too must be longer Than the river bridge at Mainz. |

| 0:59 |

Und holt mir auch zwölf Riesen, Die mussen noch stärker sein Als wie der starke Christoph Im Dom zu Köln am Rhein. |

And fetch me, too, twelve giants Who must be stronger Than St. Christopher, the great statue At the Cathedral of Cologne on the Rhine. |

| 1:18 |

Die sollen den Sarg forttragen Und senken in’s Meer hinab, Denn solchem grossen Sarge Gebührt ein grosses Grab. |

It’s they that must haul the coffin And sink it in the sea, For a great coffin like that Deserves a great grave. |

| 1:49 |

Wisst ihr, warum der Sarg wohl So gross und schwer mag sein? Ich senkt’ auch meine Liebe Und meinen Schmerz hinein. |

Do you know why the coffin really Has to be so huge and heavy? Because I sank all my love in it, And all of my great grief. |