Robert Schumann, Carnaval (1833–1835)

“Eusebius: In sculpture, the actor’s art becomes fixed. The actor transforms the sculptor’s forms into living art. The painter turns a poem into a painting. The musician sets a picture to music. Florestan: The aesthetic principle is the same in every art; only the material differs.”

Robert Schumann, 1833

Schumann’s style of piano writing has a warmth and privacy that set it apart from the music of any of the other pianist-

Such a collection is Carnaval, a set of twenty short character pieces that really are characters — musical portraits of masked guests at a Mardi Gras ball. After the band strikes up an introduction, the sad clown Pierrot arrives, followed by the pantomime figures Harlequin and Columbine, Schumann himself, two of his girlfriends masquerading under the names Estrella and Chiarina, and even the composers Paganini and Chopin. This diverse gallery provided Schumann with an outlet for his whimsy and humor, as well as all his Romantic melancholy and passion.

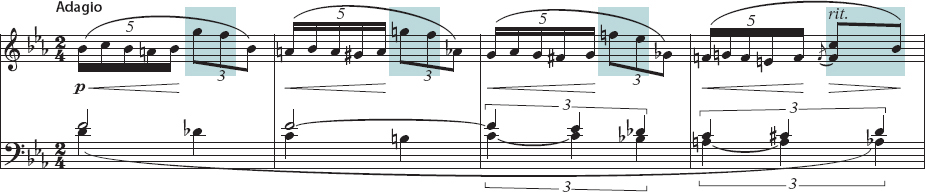

“Eusebius” Eusebius was Schumann’s pen name for his tender, dreamy self, and this little piece presents him at his most introspective. In the passage below, the yearning effect of the high notes (shaded) is compounded by the vague, languorous rhythm:

The right-

“Florestan” After “Eusebius” ends very tentatively, Schumann’s impetuous other self makes his entrance. “Florestan” is built out of a single explosive motive; the piece moves in fits and starts. At first the motive contrasts with a calmer one, but then it gets faster and faster, almost madly, ending completely up in the air. This non-