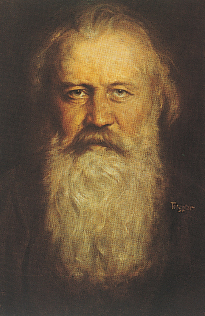

Biography

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

The son of an orchestral musician in Hamburg, Brahms was given piano lessons at an early age. By the time he was seven, he was studying with one of Hamburg’s finest music teachers. A little later he was playing the piano at dockside taverns and writing popular tunes.

A turning point in Brahms’s life came at the age of twenty when he met Robert and Clara Schumann. These two eminent musicians befriended and encouraged the young man and took him into their household. Robert wrote an enthusiastic article praising his music. But soon afterward, Schumann was committed to an insane asylum — a time during which Brahms and Clara (who was fourteen years his senior) became very close. In later life Brahms always sent Clara his compositions to get her comments and suggestions.

With another musician friend, Joseph Joachim, who was to become one of the great violinists of his time, the young Brahms signed a foolish manifesto condemning the advanced music of Liszt and Wagner. Thereafter he passed an uneventful bachelor existence, steadily turning out music — chamber music, songs, and piano pieces, but no program music or operas. He was forty-

Brahms would eventually write four magnificent symphonies, all harking back to forms used by Beethoven and even Bach, but building a restrained Romantic yearning into their expressive effect.

For a time Brahms conducted a chorus, and he wrote much choral music, including A German Requiem, a setting of sober biblical texts in German. As a conductor, he indulged his traditionalism by reviving the music of Bach and even earlier composers, but he also enjoyed the popular music of his day. He wrote waltzes (Johann Strauss, “the Waltz King,” was a valued friend), folk song arrangements, and the well-

Chief Works: Four symphonies, Tragic Overture, and the rather comical Academic Festival Overture ◼ Violin Concerto, Double Concerto for Violin and Cello, and two piano concertos ◼ Much chamber music — including quartets, quintets, and sextets; a trio for French horn, violin, and piano; a beautiful quintet for clarinet and strings ◼ Piano music and many songs ◼ Choral music, including A German Requiem and Alto Rhapsody ◼ Waltzes, Hungarian Dances

Encore: After the Violin Concerto, listen to the Clarinet Quintet; Symphony No. 3.

Image credit: Bettmann/CORBIS.