Johannes Brahms, Violin Concerto in D, Op. 77 (1878)

Concertos are always written to show off great virtuosos — who are often the composers themselves, as with Mozart, Chopin, and Liszt. Brahms wrote his one violin concerto for a close friend, Joseph Joachim, a leading violinist of the time and also a composer. Even this late in his career — Brahms was then forty-

We can appreciate Brahms’s traditionalism as far as the Classical forms are concerned by referring to the standard movement plan for the Classical concerto on page 183. Like Mozart, Brahms wrote his first movement in double-

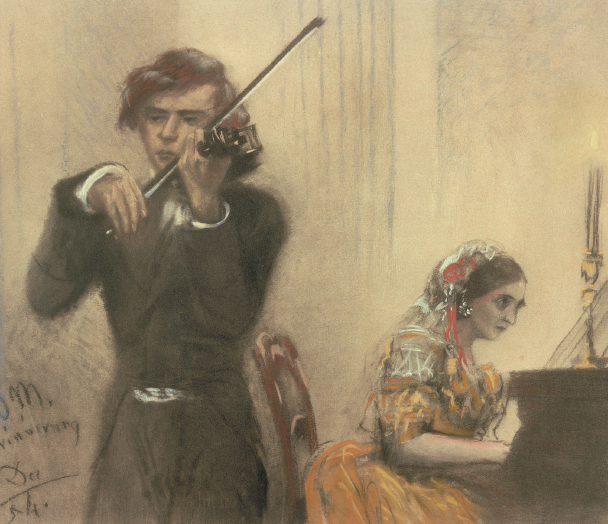

Third Movement (Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace) Giocoso means “jolly”; the first theme in this rondo, A, has a lilt recalling the spirited Gypsy fiddling that was popular in nineteenth-

The solo violin plays the theme (and much else in the movement) in double stops, that is, in chords produced by bowing two violin strings simultaneously. Hard to do well, this makes a brilliant effect when done by a virtuoso.

The theme falls into a traditional a a b a′ form; in Brahms’s hands, however, this becomes something quite subtle. Since the second a is identical to the first, except in instrumentation, the last a (a′) might be dull unless it were varied in an interesting way. Brahms manages to extend it and tighten it up at the same time, by compressing the main rhythmic figure in quicker and quicker repetitions:

These seem for a moment to disrupt or contradict the prevailing meter, a characteristic fingerprint of Brahms’s style. There are other examples in this movement.

The first rondo episode, B, a theme with a fine Romantic sweep about it, begins with an emphatic upward scale played by the solo violin, again employing double stops. This is answered by a downward scale in the orchestra in a lower range. When the orchestra has its turn to play B, the positions of the scales are reversed: The ascending scale is now in the low register, and the descending one in the high register.

The second rondo episode, C, involves a shift of meter; this charming melody — which, however, soon evaporates — is in 3/4 time:

The coda presents a version of the a phrase of the main theme in yet another meter, 6/8, in a swinging march tempo. Most of the transitions in this movement are rapid virtuoso scale passages by the soloist, who is also given two short cadenzas before the coda.