New Horizons, New Scales

Just as African masks influenced Picasso’s Demoiselles, non-

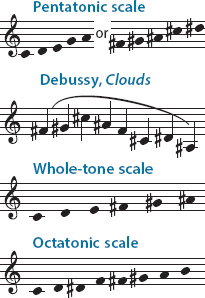

Debussy sensed a resonance between his own music and the shimmering timbres of the gamelan, and also the scales used in Indonesian music. The traditional diatonic scale had served as the foundation of Western music for so long that it was almost regarded as a fact of nature. But now composers were beginning to reconsider the basic sound materials of music. Notable among these experimenters was Charles Ives, in America. New scales were employed for themes or even whole movements, first among them the pentatonic scale, a five-

Two other new scales introduced at this time are (significantly enough) artificial constructions, derived not from non-

More important as a means of composition than the use of any of these scales was serialism, the “new language” for music invented in the 1920s by Arnold Schoenberg. As we will see in the next chapter, serialism in effect creates something like a special scale for every serial composition.