Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, Part I, “The Adoration of the Earth” (1913)

The first performance of The Rite of Spring caused a riot; the audience was shocked and infuriated by the violent, dissonant sounds in the pit and the provocative choreography on the stage, suggesting rape and ritual murder.

“My idea was that the Prelude should represent the awakening of nature, the scratching, gnawing, wiggling of birds and beasts.”

Igor Stravinsky, reminiscing in 1960 about The Rite of Spring

The ballet has no real story, and Stravinsky even said that he preferred to think of the music as an abstract concert piece. However, inscriptions on the score specify a series of ancient fertility rites of various kinds, culminating in the ceremonial choice of a virgin for sacrifice. After this she is evidently danced to death in the ballet’s second part, entitled “The Sacrifice.”

Introduction The halting opening theme is played by a bassoon at the very top of its normal register. Avant-

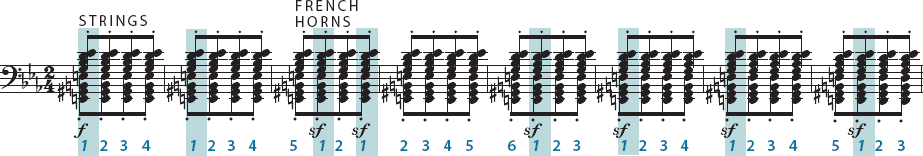

“Omens of Spring” and “Dance of the Adolescents” After a brief introduction, in which the dancers presumably register an awareness of spring’s awakening, the “Dance of the Adolescents” commences with a famous instance of Stravinskian rhythmic irregularity. (Probably the original audience started their catcalls at this point.) A single very dissonant chord is repeated thirty-

These accents completely upset ordinary meter. Instead of eight standard measures of four eighth notes — 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, etc. — Stravinsky makes us hear 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4 5, 1 2, 1 2 3 4 5 6, 1 2 3, 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4 5, 1 2 3. (For a truly bewildering experience, try beating time to this passage.) Yet these irregular rhythms are also exhilarating, and they certainly drive the music forward in a unique way.

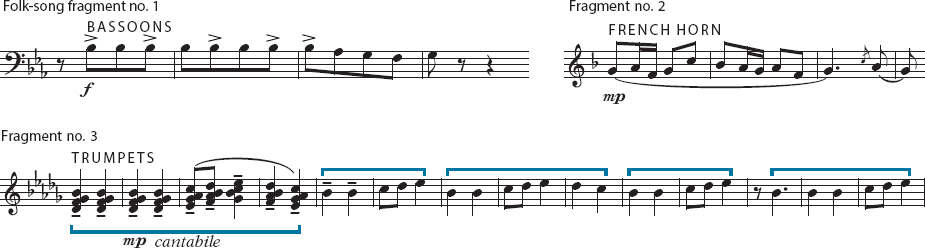

The repeating chords are now overlaid with new motives, derived from Russian folk song. The motives are repeated with slightly different rhythms and at slightly different lengths. This is Stravinsky’s distinctive type of ostinato, a technique we have met with in many other kinds of music (see pages 88, 94, and 119); the ostinato is indicated by brackets in the example below. Like Debussy, Stravinsky tends to concentrate on small melodic fragments, but whereas Debussy soon abandons his fragments, Stravinsky keeps repeating his in this irregular, almost obsessive way.

“The Game of Abduction” New violence is introduced with this section, a whirlwind of brilliant rhythms, with much frantic pounding on the timpani.

“Round Dances of Spring” After a moment of respite, a short, quiet introduction conveys a remarkably desolate, empty feeling, partly as a result of its novel orchestration: a high (E ) clarinet and low (alto) flute playing two octaves apart. Then a slow dragging dance emerges, built out of the third folk-

The strong downbeat makes the meter hypnotic — but one or two added or skipped beats have a powerful animating effect. The dance reaches a relentless climax with glissando (sliding) trombones, gong, cymbals, and big drum. After a sudden fast coda, the wildlife fanfares of the introduction return to conclude the section.

Four more sections follow our selection in Part I of The Rite of Spring. The dynamic “Games of the Rival Tribes” introduces two more folk-

What is conspicuously absent from any of this is emotionality. Tough, precise, and barbaric, it is as far from old-