SCHOENBERG AND SERIALISM

Of all early twentieth-century composers, Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) was the most keenly aware of the problem caused by ever-broadening dissonance and atonality. The problem, to put it simply, was the clear and present danger of chaos. In the early 1920s Schoenberg found a way that he felt would impose order or control over the newly “emancipated” elements of music.

This resulted in the twelve-tone system, defined by Schoenberg as a “method of composing with the twelve tones solely in relation to one another” — that is, not in relation to a central pitch, or tonic, which was no longer to act as a point of reference for the music. This method became known as serialism. Serialism can be regarded as the ultimate systematizing of the chromaticism developed by Romantic composers, especially Richard Wagner (see page 226).

Schoenberg’s method of composing with the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale held them to a fixed order. An ordered sequence of the twelve pitches is called a twelve-tone row, or series: hence the term serialism. For any composition, he would determine a series ahead of time and maintain it (the next piece would have a different series).

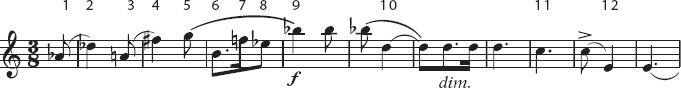

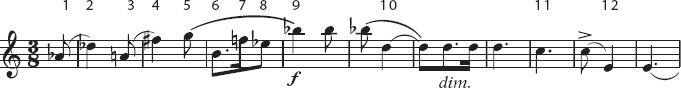

What does “maintain” mean in this context? It means that Schoenberg composed by writing notes only in the order of the work’s series, or of certain carefully prescribed other versions of the series (see below). As a general rule, he went through the entire series without any repetitions or backtracking before starting over again. However, the pitches can appear in any octave, high or low. They can stand out as melody notes or blend into the harmony. They can assume any rhythm: In the example below, pitch 10 lasts sixteen times as long as pitch 7.

Phrase of a Schoenberg melody using a twelve-tone series. Arnold Schoenberg, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1942).Used by permission of Belmont Music Publishers.

And what are those other “versions” of the series? The series can be used not only in its original form but also be transposed, that is, the same note ordering can start from any note in the chromatic scale. The composer can also present the series backward (called “retrograde”) or inverted, that is, with the intervals between notes turned upside down. The basic idea of serialism may seem to impose order with a vengeance by putting severe limits on what a composer can do. But once the versions are taken into consideration, an enormous number of options becomes available.

Part of the point of twelve-tone composition is that each piece has its own special “sound world” determined by its series. This permeates the whole piece. The next piece has a new series and a new sound world.

Serialism can be regarded as the end result of an important tendency in nineteenth-century music, the search for ever stronger means of unity within individual compositions. We have traced the “principle of thematic unity” in music by Berlioz, Wagner, and others (see page 231). A serial composition is, in a sense, totally unified, since every measure of it shares the same unique sound world. On its own special terms, Schoenberg’s serialism seemed to realize the Romantic composers’ ideal of unity.

The Second Viennese School

The two composers after Schoenberg quickest to adopt his serialism, Anton Webern and Alban Berg, had both studied with him in Vienna before World War I. Together the three make up the Second Viennese School. They were very different in musical personality, and serialism did not really draw them together; rather it seems to have accentuated the unique qualities of each composer.

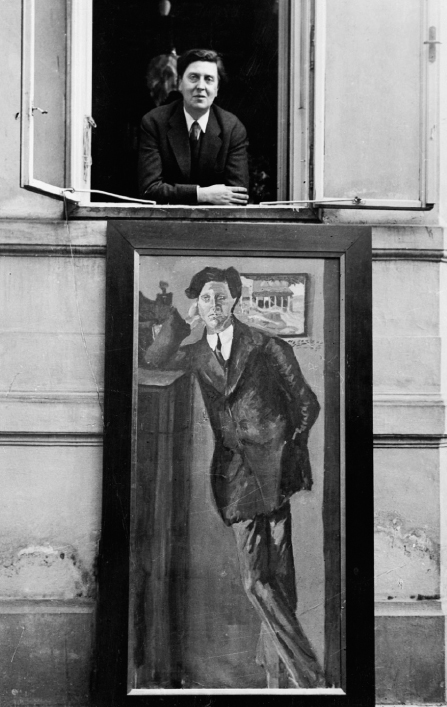

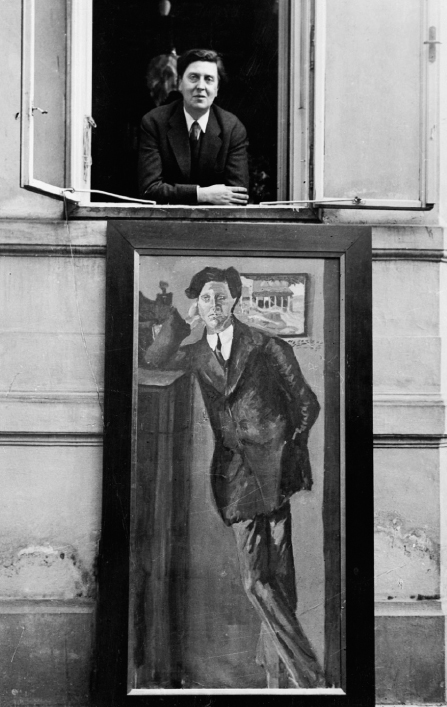

For once, a composer picture that’s different: Alban Berg looks out over a life-sized portrait of himself painted by Arnold Schoenberg. Bettmann/CORBIS.

Anton Webern (1883–1945) was an unspectacular individual whose life revolved around his strangely fragile artistic accomplishment. Despite his aristocratic background, he became a devoted conductor of the Vienna Workers’ Chorus, as well as holding other, rather low-profile conducting positions.

From the start, Webern reacted against the grandiose side of Romanticism, as represented by the works of Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler. He turned his music about-face, toward abstraction, atomization, and quiet: so quiet that listening to his music, one listens to the rests almost as much as to the notes themselves. His compositions are all extremely brief and concentrated (we discuss one of the briefest on page 362). Webern’s entire musical output can fit on three CDs.

But both Webern’s vision of musical abstraction and his brilliant use of serialism made him a natural link between the first avant-garde phase of modernism, around World War I, and the second. Though he was killed in 1945, shot in error by a member of the American occupying forces in Austria, his forward-looking compositions caught the imagination of an entire generation of composers after World War II.

Alban Berg (1885–1935), in contrast, looked back; more than Schoenberg and certainly more than Webern, he kept lines of communication open to the Romantic tradition by way of Mahler. Berg’s first opera, Wozzeck, was an immediate success on a scale never enjoyed by the other Second Viennese composers. His second opera, Lulu (1935), is now also a classic, though it made its way slowly — Berg had only partly orchestrated Act III when he died, and both operas were banned by the Nazis.

Like Webern, Berg met a bizarre end: He died at the age of fifty as a result of an infected insect bite. After his death, it came out that he had been secretly in love with a married woman, and had employed a musical code to refer to her and even to address her in his compositions — among them a very moving Violin Concerto (1935), his last work.