Bebop

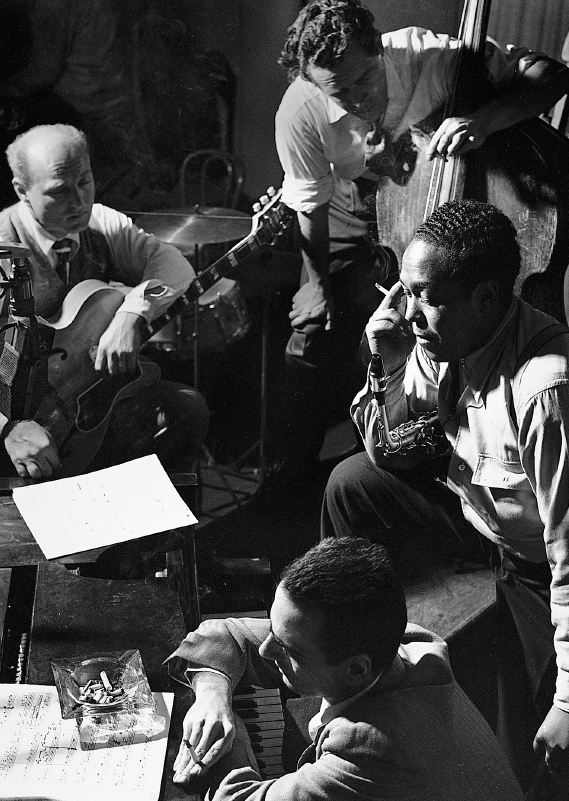

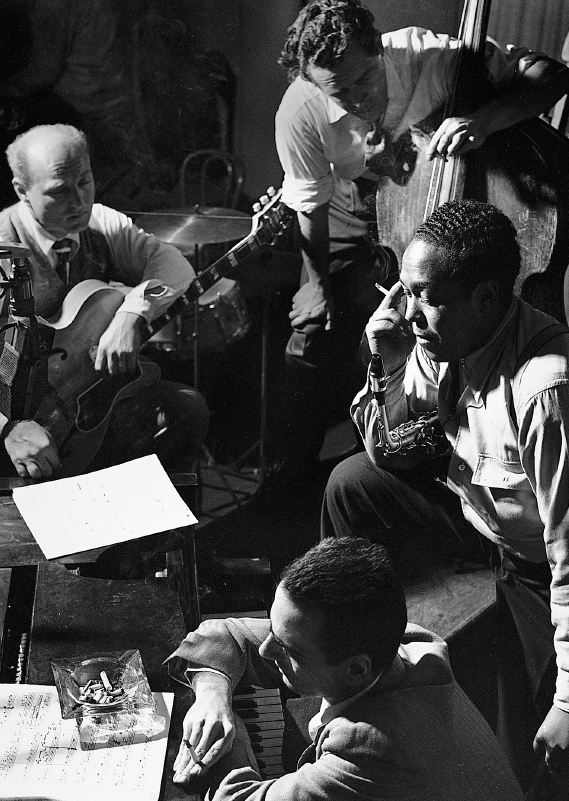

In a recording studio, Charlie Parker listens to a playback as the other musicians wait for his reaction. Will he approve this take of the standard they are recording, or will they have to do another? © Herman Leonard Photography LLC.

During the early 1940s, young black jazz musicians found it harder to get work than white players in big bands. When they did get jobs, the setup discouraged free improvisation, the life and soul of jazz; the big bands seemed to have co-opted and distorted a style grown out of black experience. These musicians got together in small groups after work for jam sessions at clubs in Harlem, in New York City. There they developed a new style that would later be called bebop. Contrasting sharply with the big bands, the typical bebop combo (combination) was just trumpet and saxophone, with a rhythm section including piano.

Bebop was a determined return to improvisation, then — but improvisation at a new level of technical virtuosity. “That horn ain’t supposed to sound that fast,” an elder musician is said to have complained to bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker. In addition to unprecedented velocity, Parker and leading bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (1917–1993) cultivated hard, percussive sounds and sharp, snap rhythms (one derivation of the term bebop). The smooth swing of the big bands was transformed into something more aggressive and exciting.

Equally radical was the treatment of harmony in bebop. New Orleans jazz used simple, in fact naïve, harmonies. The big-band, swing arrangers used much more sophisticated ones. Bebop musicians took these complex harmonies and improvised around them in a more and more “far-out” fashion. In some stretches of their playing, even the tonality of the music was obscured. Bebop melodies grew truly fantastic; the chord changes became harder and harder to follow.

“Playing [be]bop is like playing Scrabble with all the vowels missing.”