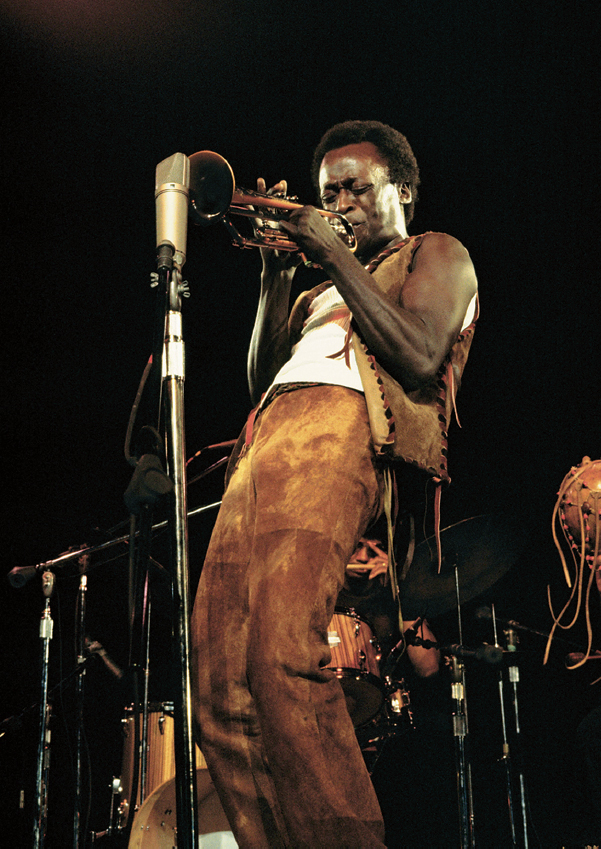

Miles Davis (1926–1991), Bitches Brew (1969)

Trumpeter Miles Davis, one of the most innovative figures in the whole history of jazz, started out playing with Charlie Parker and other bebop musicians, as we heard in “Out of Nowhere.” Soon, however, he realized that his own aptitude (or at least one of his aptitudes) was for a more relaxed and tuneful kind of melody. Davis’s style went through many stages — from bebop to cool jazz to modal jazz and beyond — as he worked in various groups with a veritable who’s who of modern jazz artists.

Bitches Brew, one of his biggest hits, was also one of his most original. A conscious (and controversial) attempt to blend jazz with rock — fusion jazz, as it came to be called — the album used a rhythm section with electric guitar, bass, and two electric keyboards in addition to regular jazz drums, acoustic bass, and augmented percussion. Instead of the traditional chord changes of jazz, this group produced repetitive, rocklike rhythms of great variety and, often, delicacy. This backdrop provides an unlikely but also unforgettable setting for Davis’s haunting improvisations.

Our selection covers a solo from the title track of Bitches Brew. Before Davis begins, the electric piano and guitar pick out rhythmic patterns against a quiet jazz drum background; mostly the electric guitar has isolated single notes and the electric piano has syncopated, dissonant chords. From the beginning a rocklike ostinato sounds quietly on the electric bass guitar.

The trumpet solo starts with short patterns of relatively long notes, a Davis signature. The mood is meditative, almost melancholy: an evocation of the blues. The backdrop tapestry of sounds grows thicker. Soon Davis is employing more elaborate patterns — a string of repeated notes, scalelike passages up and down — but the effect is, in its own way, as repetitive as the backdrop. Then he explodes into a series of little snaps, a recollection of bebop. As the whole group drives harder and harder, we realize that Davis has now arrived at a wild, free ostinato in the high register. The solo sinks down again after a climactic high trumpet squeal, another Davis hallmark.

LISTEN

Bitches Brew (excerpt)

| 0:00 | Backdrop |

| 0:42 | Dies down |

| 1:05 | Trumpet solo |

| 2:41 | Trumpet ostinato |

| 3:20 | Climax |

With jazz-