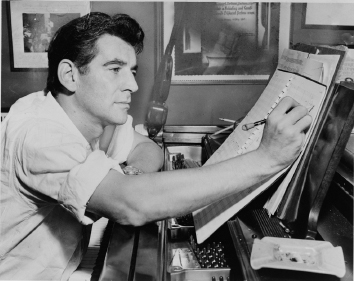

Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), West Side Story (1957)

Leonard Bernstein was one of the most brilliant and versatile musicians ever to come out of America, the consummate crossover artist before the term was invented. Composer of classical symphonies and hit musicals, internationally acclaimed conductor, pianist, author, and mastermind of wonderful shows in the early days of television, he won Grammys, Emmys, and a Tony.

West Side Story (1957) boasts three exceptional features — its moving story, its sophisticated score, and its superb dances, created by the great American choreographer Jerome Robbins. The musical, by turns funny, smart, tender, and enormously dynamic, gave us song classics such as “Maria” and “Tonight.” Our recording of West Side Story is from the soundtrack to the 1961 movie version of the show.

Background Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet tells of young lovers frustrated and driven to their deaths by a meaningless feud between their families, the Montagues and the Capulets of Verona. West Side Story transplants this plot to a turf war between teenage gangs on the West Side of Manhattan.

LISTEN

“The great thing about conducting is that you don’t smoke and you breathe in great gobs of oxygen.”

Chain-

In Shakespeare, the feud is a legacy from the older generation, but in West Side Story the bitter enmity belongs to the kids themselves, though it has ethnic overtones. The Jets are whites, the Sharks Puerto Ricans.

Bernardo, leader of the Sharks, is livid when he learns that his sister Maria is in love with Jet Tony. As in Shakespeare, one Jet (Capulet) and one Shark (Montague) die tragically onstage, in a street fight. Tony is shot in revenge, and Maria is left distraught.

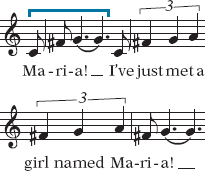

Some of the transpositions into the modern world are ingenious. Shakespeare’s famous soliloquy “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” shows the lovestruck Juliet fondly repeating her lover’s name; Tony cries “Maria” over and over again in his famous song of that title. (An aria in an opera or a song in a musical is, in fact, often equivalent to a soliloquy in a play.) And whereas Shakespeare’s young lovers fall in love at a Capulet masked ball, which Romeo has crashed, Bernstein’s meet at a gym dance organized by a clueless teacher who hopes to make peace between the gangs.

Cha-

The charm of the fragile cha-

Meeting Scene Tony and Maria catch sight of one another. The cha-

And when Tony gets to sing the big romantic number, “Maria,” the music is yet another transformation of the cha-

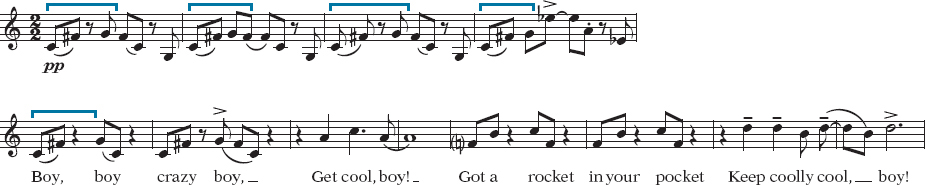

“Cool” Later in the action, the Jet Ice tries to persuade his troops to stay calm after the death of their leader, Riff, in the rumble with the Sharks. The main production number of Act I, it consists of an introduction, again with a voice-

The song’s introduction uses the motive of the cha-

LISTEN

Boy, boy, crazy boy,

Get cool, boy!

Got a rocket in your pocket,

Keep coolly cool, boy!

Don’t get hot ’cause, man, you got

Some high times ahead.

Take it slow, and, Daddy-

You can live it up and die in bed!

After the introduction, Ice sings two stanzas of his song, in 1950s “hip” street language. There is a steady jazz percussion accompaniment.

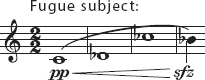

The dance that follows, subtitled “Fugue,” is accompanied throughout by the soft jazz drumbeat. First played by muted trumpet, the fugue subject consists of four slow notes, with an ominous snap at the end of the last of them. Soon another theme — the fugue countersubject — comes in, played by flute and vibraphone, featured instruments of 1950s “cool jazz.” The two themes combine in counterpoint, along with fragments of the introduction, getting louder and more intricate as the dance proceeds. Bernstein must have thought that fugue, about the most controlled of musical forms, would depict perfectly the Jets’ effort to stay cool.

But things appear to get out of hand toward the end of the dance. The music stomps angrily and breaks into electrifying improvised drum solos. The Jets yell various words taken from the song, and the song’s melody returns, orchestrated in the exuberant, brash style of a big swing band. While the brasses blare away on the tune, breaks (see page 386) are played by the reeds at the end of each line.

To conclude, the Jets sing parts of “Cool” quietly, prior to its atmospheric conclusion. The vibraphone recollects the fugue countersubject.

LISTEN

“Cool”

| 0:14 | Ice: “Cool” |

| 1:12 | Fugue begins. |

| 2:40 | Fugue breaks down. |

| 3:10 | Band version of “Cool” |

| 3:39 | Jets: “Cool” |

| 4:09 | Countersubject |