3 | Tone Color

At whatever pitch, and whether loud or soft, musical sounds differ in their general quality, depending on the instruments or voices that produce them. Tone color and timbre (tám-

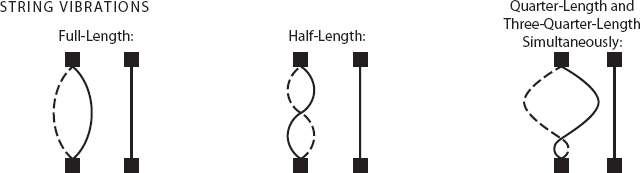

Tone color is produced in a more complex way (and a more astonishing way) than pitch and dynamics. Piano strings and other sound-

The diagrams above attempt to illustrate this. Musicians call these fractional vibrations overtones. They are much lower in amplitude — that is, softer — than the main vibrations; for this reason, we hear overtones not as distinct pitches, but somehow as part of the string’s basic or fundamental pitch. The amount and exact mixture of overtones are what give a sound its characteristic tone color. A flute has few overtones. A trumpet has many.

Musicians make no attempt to tally or describe tone colors; about the best one can do is apply imprecise adjectives such as bright, warm, ringing, hollow, or brassy. Yet tone color is surely the most easily recognized of all musical elements. Even people who cannot identify instruments by name can distinguish between the smooth, rich sound of violins playing together, the bright sound of trumpets, and the woody croaking of a bassoon.

The most distinctive tone color of all, however, belongs to the first, most beautiful, and most universal of all the sources of music — the human voice.