Pitch Notation

The letter names A B C D E F G are assigned to the origi-

The Staff: Ledger Lines For the notation of pitch, notes are placed on a set of five parallel lines called a staff. The notes can be put on the lines of the staff, in the spaces between them, or right at the top or bottom of the staff:

Above and below the regular five lines of the staff, short extra lines can be added to accommodate a few higher and lower notes. These are called ledger lines.

Clefs Nothing has been said so far about which pitch each position on the staff represents. To clue us in to precise pitches, signs called clefs (French for “key” or “clue”) are placed at the beginning of each staff. Clefs calibrate the staff; that is, they connect one of the five lines of the staff to a specific pitch.

Thus in the treble clef, or G clef ![]() , the spiral in the middle of this antique capital G curls around line 2, counting up from the bottom of the staff. Line 2, then, is the line for the pitch G — the first G above middle C. In the bass clef, or F clef

, the spiral in the middle of this antique capital G curls around line 2, counting up from the bottom of the staff. Line 2, then, is the line for the pitch G — the first G above middle C. In the bass clef, or F clef ![]() , the two dots straddle the fourth line up. The pitch F goes on this line — the first F below middle C. Complicated! But not too hard to learn.

, the two dots straddle the fourth line up. The pitch F goes on this line — the first F below middle C. Complicated! But not too hard to learn.

Adjacent lines and spaces on the staff have adjacent letter names, so we can place all the other pitches on the staff in relation to the fixed points marked by the clefs:

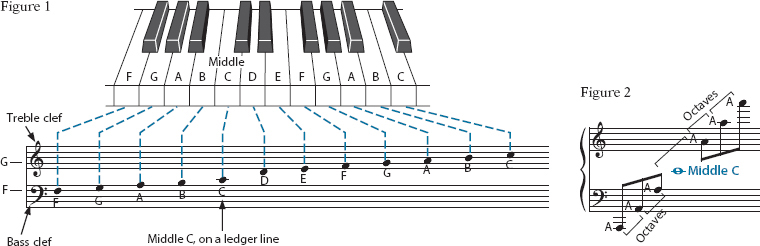

There are other clefs, but these two are the most common. Used in conjunction, they accommodate the maximum span of pitches without overlapping. The treble and bass clef staffs fit together as shown in Figure 1 below.

The notation of six A’s, covering five octaves, requires two staffs and seven ledger lines (see Figure 2).

Sharps and Flats; Naturals The pitches produced by the black keys on the piano are not given letter names of their own. (This is a consequence of the way they arose in history; see page 23.) Nor do they get their own individual lines or spaces on the staffs. The pitch in between A and B is called A sharp (or A![]() , using the conventional sign for a sharp), meaning “higher than A.” It can also be called B flat (B

, using the conventional sign for a sharp), meaning “higher than A.” It can also be called B flat (B![]() ), meaning “lower than B.” In musical notation, the signs

), meaning “lower than B.” In musical notation, the signs ![]() and

and ![]() are placed on the staff just before the note that is to be sharped or flatted.

are placed on the staff just before the note that is to be sharped or flatted.

Which of these two terms is used depends partly on convenience, partly on convention, and partly on theoretical considerations that do not concern us here. In the example below, the third note, A![]() , sounds just like the B later in the measure, but for technical reasons the composer (Béla Bartók) notated it differently.

, sounds just like the B later in the measure, but for technical reasons the composer (Béla Bartók) notated it differently.

The original pitches of the diatonic scale, played on the white keys of the piano, are called “natural.” If it is necessary to cancel a sharp or a flat within a measure and to indicate that the natural note should be played instead, the natural sign is placed before a note ![]() or after a letter (A

or after a letter (A![]() ) to show this. The following example shows A sharp and G sharp being canceled by natural signs:

) to show this. The following example shows A sharp and G sharp being canceled by natural signs:

Key Signatures In musical notation, it is a convention that a sharp or flat placed before a note will also affect any later appearance of that same note in the same measure — but not in the next measure.

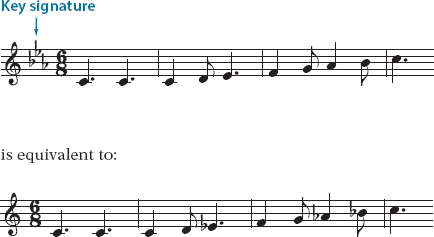

There is also a way of specifying that certain sharps or flats are to be applied throughout an entire piece, in every measure, and in every octave. Such sharps and flats appear on the staffs at the very beginning of the piece, even prior to the time signature, and at the beginning of each staff thereafter. They constitute the key signature: