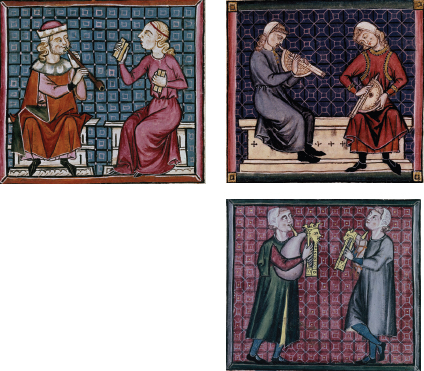

Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377), Chanson, “Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient”

Machaut left us numerous examples of secular polyphony, that is, polyphony independent from the church. He composed many motets using isorhythmic techniques. And, though he was still close enough to the trouvères to write beautiful monophonic songs, he also adapted their old tradition of chivalric love songs to complex, ars nova polyphony. These songs, or chansons (shahn-

“Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient,” a chanson with four voices, is an excellent example of non-

Because of this melismatic style, the song is much longer than Bernart’s “La dousa votz.” Each stanza takes about two minutes in our performance, and only the first is included here. Still, the form of “Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient” is identical to that of Bernart’s song. Each stanza falls into an a a′ b arrangement; this was one of several standardized song forms Machaut adapted from the trouvères. Given the length of Machaut’s song, a letter now stands for a whole section rather than a melodic phrase or two. Each section comes to a clear stop on a strong cadence. The three sections are signaled in the Listen box that follows.

The most general impression of this song is of a lively and flowing set of intertwining melodies. The words — hard to follow because of the abundant melismas — seem to be little more than an excuse for the complex polyphony. Certainly the music does not show any obvious attempt to reflect the meaning or emotion of the poem. We will see in Chapter 7 that, by the time of the Renaissance, this rather neutral relation of music and words would change.

LISTEN

Machaut, “Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient”

| 0:00 | a | Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient | Lady, source of all my joy, |

| Je ne vous puis trop amer et chierir | I can never love or cherish you too much, | ||

| 0:35 | a′ | N’assés loer, si com il apartient | Or praise you as much as you deserve, |

| Servir, doubter, honourer n’obeïr. | Or serve, respect, honor, and obey you. | ||

| 1:19 | b | Car le gracious espoi, | For the gracious hope, |

| Douce dame, que j’ay de vous vëoir, | Sweet lady, I have of seeing you, | ||

| Me fait cent fois plus de bien et de joie | Gives me a hundred times more joy and boon | ||

| Qu’en cent mille ans desservir ne porroie. | Than I could deserve in a hundred thousand years. |