Global Perspectives

Sacred Chant

The vast number of societies that exist or that have existed in this world all generated their own music — or, as we say, their own different “musics.” Often they are very different indeed; the first time South African Zulus heard Christian hymn singing they were amazed as much as the missionaries were when they first heard Zulu music.

Yet for all their diversity, the musics of the world do show some parallels, as we are going to see in the Global Perspectives sections of this book. There are parallels of musical function in society, of musical technique, and sometimes of both together.

Often these parallels come about as the result of influences of one society on another — but influences are never accepted without modification and the blending of a foreign music with native music. At other times parallels appear in musics that have nothing whatsoever to do with one another. Considering all these parallels, we have to believe that certain basic functions for music and certain basic technical principles are virtually universal in humankind.

One of these near-

Islam: Reciting the Qur’an

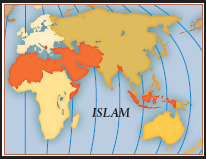

Another highly elaborate tradition of chant is found in Islam, practiced today by about a fifth of the world’s population, and the dominant religion in some fifty nations. Across all of Islam, the revelations of the prophet Muhammad gathered in the Qur’an (or Koran) are chanted or sung in Arabic. Muhammad himself is said to have enjoyed this melodic recitation.

Usually Qur’anic recitation is rigorously distinguished from all types of secular music making. It is thought of as “reading” the sacred text aloud, not singing it; nonreligious activities such as singing or playing instruments might be referred to as music (musiqi), but reading the Qur’an is not.

Given these distinctions, it is not surprising that Qur’anic recitation, like Gregorian chant, is monophonic and nonmetric, and does not involve instruments. It aims, above all else, to convey the Qur’anic text in a clearly comprehensible manner. Unlike plainchant, it has been passed along in oral tradition down to the present day; it has resisted the musical notation that came to be a part of the Gregorian tradition already in the Middle Ages. To this day, great Islamic chanters sing the whole 114-

"Ya Sin"

Our excerpt is the beginning of a long recitation of one of the most highly revered chapters from the Qur’an. It is titled “Ya Sin” and is recited in times of adversity, illness, and death. A skilled reciter, Hafíz Kadir Konya, reads the verses in a style midway between heightened speech and rhapsodic melody. His phrases correspond to lines of the sacred text, and he pauses after every one. He begins:

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

Ya Sin.

By the wise Qur’an,

Lo! thou art of those sent

On a straight path,

A revelation of the Mighty, the Merciful,

That thou mayst warn a folk whose fathers were not warned, so they are heedless.

Already hath the word proved true of most of them, for they believe not.

In his first phrases, Konya begins at a low tonic and gradually expands his range to explore pitches around it. By 0:39, he reaches a pitch central to his melody, higher than the tonic. The succeeding phrases circle around this pitch, reciting words on it and decorating it with ornamental melodic formulas of varying intricacy. In this regard, it is a bit like Gregorian recitation, only more elaborate in its melodies.

The Azan

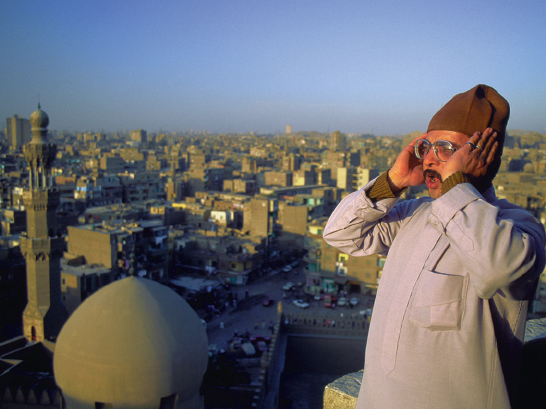

Like Gregorian chant, Islamic chanting has developed a wide variety of approaches and styles. The best-

The muezzin traditionally delivers his azan from the minaret, a tower attached to the mosque, and later inside the mosque to begin the prayers. In Islamic cities today, the azan is often broadcast over loudspeakers to enable it to sound over modern urban noises.

Hawai’ian Chant

We should not be too surprised to find certain broad similarities between Qur’anic and Gregorian chant. Both Christianity and Islam emerged from the same region, the Middle East, and Muhammad drew on elements of Christian doctrine in forming his new religion. He counted Jesus Christ as one of the Islamic prophets.

It is more surprising to find some of the same features in religious chant from halfway around the globe, in Polynesia — in Hawai’ian prayer songs, or mele pule (mél-

Our brief example combines fragments of two chants (the division comes at 0:24). The first is a song to the fire goddess Pele, the second an invocation to a godlike chief. Like Gregorian and Qur’anic recitation, and like all traditional Hawai’ian song, these mele are monophonic. They are also almost monotonal, with only one prominent pitch other than the central reciting tone.

The chants take their rhythms from the words and show little trace of meter. Their simple melody is ornamented subtly with various shifts of vocal delivery. The most prominent of these is a clear, pulsating, almost sobbing vibrato, or wavering pitch, that the singer, Kau’i Zuttermeister, introduces on long syllables. This technique, called i’i, is a stylistic feature prized in many types of traditional Hawai’ian song. It is felt to endow melodies with special, deep emotion.

A Navajo Song

One more example of chant comes to us from Native American traditions. In these, too, singing is closely allied with the sacred. Song plays a role in healing, hunting, social rituals, and — embracing all these activities — in human relations with gods, spirits, and ancestors. Most Native North American song is monophonic, like the Hawai’ian, Arabic, and Western chants we have heard. Unlike them, it is usually accompanied by drums or rattles of one sort or another.

Our example comes from the Navajo nation of the Four Corners area of the American Southwest. It is called “K′adnikini′ya′,” which means “I’m leaving,” and it dates from the late nineteenth century.

Just as individual Gregorian chants have their assigned places in Catholic services, so this chant has its own special role. It is sung near the end of the Enemy Way ceremony, a central event of Navajo spiritual life. In this solemn ceremony, warriors who have come in contact with the ghosts of their enemies are purified and fortified. Such purification is still performed today, sometimes for the benefit of U.S. war veterans.

“K′adnikini′ya′” falls into a group of Navajo sacred songs known as ho′zho′ni′ songs, and you will hear the related word ho′zhon′go (“beautiful,” “holy”) sung alongside k′adnikini′ya′ to end each of the seven central phrases of the song. Every phrase of the song begins with the syllables hé-yuh-

The melody of “K′adnikini′ya′,”

LISTEN

“K′adnikini′ya′”

| 0:00 | a | Refrain |

| 0:12 | a | Refrain repeated |

| 0:22 | b | 7 parallel phrases, each of 11 drum strokes |

| 1:06 | a | Refrain |