Imitation

Most polyphony at the beginning of the fifteenth century was non-

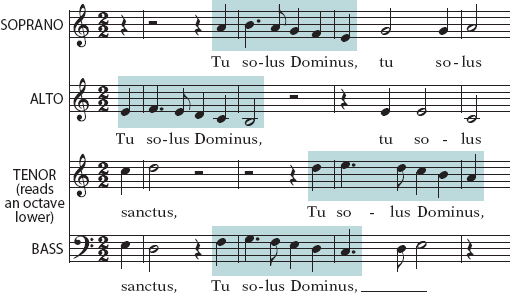

By its very nature, imitative texture depends on a carefully controlled balance among multiple voice parts. A first voice begins with a motive (see page 25) designed to fit the words being set. Soon other voices enter, one by one, singing the same motive and words, but at different pitch levels; meanwhile the earlier voices continue with new melodies that complement the later voices. Each voice has a genuinely melodic quality, none is mere accompaniment or filler, and none predominates for very long.

We can get an impression of the equilibrium of imitative polyphony from its look on the page, even without reading the music exactly. The following excerpt is from the score of Josquin Desprez’s Pange lingua Mass: