Homophony

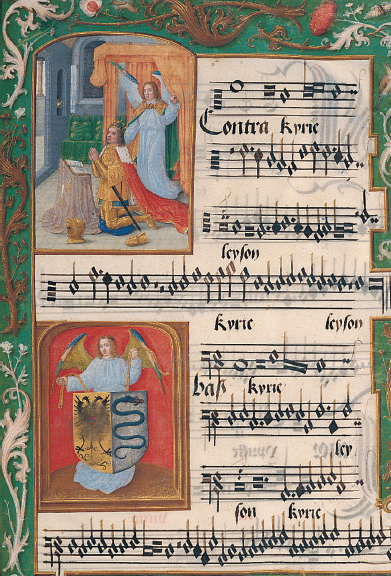

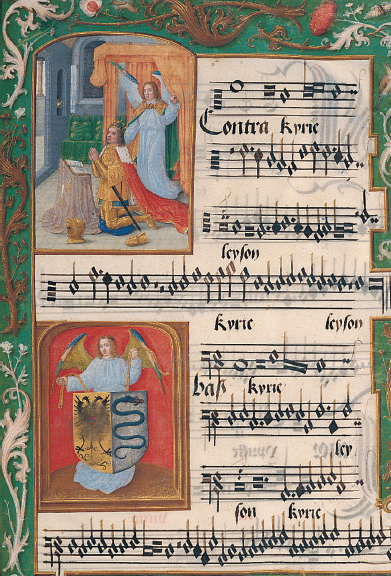

A Kyrie from a dazzling Renaissance book of Mass music. Such handcrafted treasures were rarely used in music making, though many plainer manuscripts saw much use. The man who commissioned this one is shown praying with an angel in the top left. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

Almost all polyphony involves some chords, as a product of its simultaneously sounding melodies. But in the music of Machaut, for example, the chords are more of a by-product. Late medieval composers concentrated on the horizontal aspects of texture at the expense of vertical ones (see page 29), delighting in the separateness of their different voice parts. The chords that resulted from the interplay of these parts were a secondary consideration.

A major achievement of the High Renaissance style was to create a rich chordal quality out of polyphonic lines that still maintain a quiet sense of independence. Composers also used simple homophony — passages of block chord writing. They learned to use homophony both as a contrast to imitative texture and as an expressive resource in its own right.

Another Kyrie, this one printed around 1500—the earliest beginnings of music-printing technology. The circulation of music (as of books, maps, images, and data in general) skyrocketed with the great Renaissance invention of the printing press.