Thomas Weelkes (c. 1575–1623), Madrigal, “As Vesta Was from Latmos Hill Descending” (1601)

Thomas Weelkes never rose beyond the position of provincial cathedral organist-

Weelkes’s contribution to The Triumphs of Oriana is a fine example of a madrigal of the lighter kind. (Weelkes also wrote serious and melancholy madrigals.) After listening to the music of Josquin and Palestrina, our first impression of “Vesta” is one of sheer exuberant brightness. Simple rhythms, clear harmonies, crisp melodic motives — all look forward to music of the Baroque era and beyond. This music has a modern feel about it.

The next thing likely to impress us is the elegance and liveliness with which the words are declaimed. Weelkes nearly always has his words sung in rhythms that would seem quite natural if the words were spoken, as shown in the margin (where — stands for a long syllable, ˘ for a short one). The declamation is never less than accurate, and it is sometimes expressive: The rhythms make the words seem imposing in the second phrase, dainty in the third.

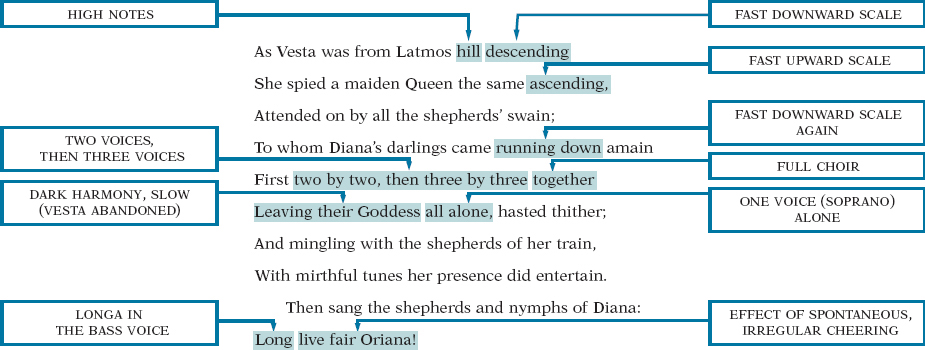

As for the word painting, that can be shown in a tabular form:

(The “maiden Queen” is Elizabeth, and “Diana’s darlings” are the Vestal Virgins, priestesses of Vesta, the Roman goddess of hearth and home. The archaic word amain means “at full speed.”)

This brilliant six-