Respond to a Reading: A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen

Respond to a Reading: Henrik Ibsen, A Doll’s House

Read the scene from the opening of A Doll’s House below and respond to the questions in the margin. When you are done, “submit” your response.

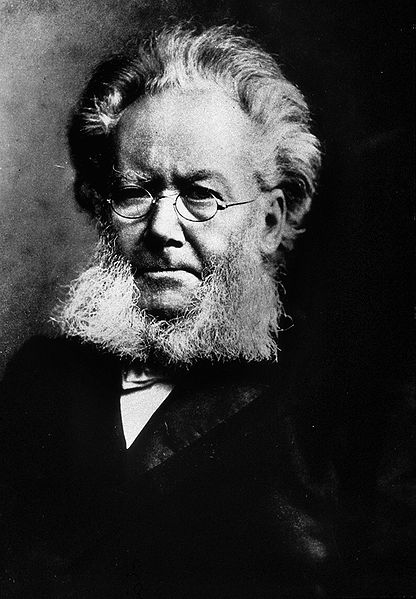

Henrik Ibsen

(1828–1906)

Henrik Ibsen was born in Skien, Norway (a seaport about one hundred miles south of Oslo), the son of a wealthy merchant. When Ibsen was eight, his father’s business failed, and at fifteen, he was apprenticed to an apothecary in the tiny town of Grimstad. He hated this profession. For solace, he read poetry and theology and began to write. When he was twenty-two, he became a student in Christiania and published his first play.

In 1851, Ibsen’s diligent writing earned him an appointment as “theater-poet” to a new theater in Bergen, where he remained until 1857, learning both the business and the art of drama. He wrote several plays based on Scandinavian folklore, held positions at two theaters in Christiania, and married. When he was thirty-six, he applied to the government for a poet’s pension, a stipend that would have permitted him to devote himself to writing. The stipend was refused. Enraged, he left Norway, and though he was granted the stipend two years later, he spent the next twenty-seven years in Italy and Germany, where he wrote the realistic social dramas that established his reputation as the founder of modern theater.

Such plays as Ghosts (1881), An Enemy of the People (1882), and A Doll’s House (1878) inevitably generated controversy as Ibsen explored venereal disease, the stupidity and greed of the “compact majority,” and the position of women in society. In 1891, he returned to live in Christiania, where he was recognized and honored as one of Norway’s (and Europe’s) finest writers.

A Doll’s House

(Translated by R. Farquharson Sharp)

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Torvald Helmer

Nora, his wife

Doctor Rank

Mrs. Linde

Nils Krogstad

Helmer’s three small children

Anne, their nurse

A Housemaid

A Porter

Scene: The action takes place in Helmer’s house.

ACT I

Scene: A room furnished comfortably and tastefully, but not extravagantly. At the back, a door to the right leads to the entrance-hall, another to the left leads to Helmer’s study. Between the doors stands a piano. In the middle of the left-hand wall is a door, and beyond it a window. Near the window are a round table, arm-chairs, and a small sofa. In the right-hand wall, at the farther end, another door; and on the same side, nearer the footlights, a stove, two easy chairs, and a rocking-chair; between the stove and the door, a small table. Engravings on the walls; a cabinet with china and other small objects; a small book-case with well-bound books. The floors are carpeted, and a fire burns in the stove. It is winter.

A bell rings in the hall; shortly afterwards the door is heard to open. Enter Nora, humming a tune and in high spirits. She is in outdoor dress and carries a number of parcels; these she lays on the table to the right. She leaves the outer door open after her, and through it is seen a Porter who is carrying a Christmas Tree and a basket, which he gives to the Maid who has opened the door.

1

Nora: Hide the Christmas Tree carefully, Helen. Be sure the children do not see it until this evening, when it is dressed. (To the Porter, taking out her purse.) How much?

Porter: Sixpence.

Nora: There is a shilling. No, keep the change. (The Porter thanks her, and goes out. Nora shuts the door. She is laughing to herself, as she takes off her hat and coat. She takes a packet of macaroons from her pocket and eats one or two; then goes cautiously to her husband’s door and listens.) Yes, he is in. (Still humming, she goes to the table on the right.)

Helmer (calls out from his room): Is that my little lark twittering out there?

Nora (busy opening some of the parcels): Yes, it is!

Helmer: Is it my little squirrel bustling about?

Nora: Yes!

Helmer: When did my squirrel come home?

Nora: Just now. (Puts the bag of macaroons into her pocket and wipes her mouth.) Come in here, Torvald, and see what I have bought.

Helmer: Don’t disturb me. (A little later, he opens the door and looks into the room, pen in hand.) Bought, did you say? All these things? Has my little spendthrift been wasting money again?

Nora: Yes but, Torvald, this year we really can let ourselves go a little. This is the first Christmas that we have not needed to economise.

Helmer: Still, you know, we can’t spend money recklessly.

Nora: Yes, Torvald, we may be a wee bit more reckless now, mayn’t we? Just a tiny wee bit! You are going to have a big salary and earn lots and lots of money.

Helmer: Yes, after the New Year; but then it will be a whole quarter before the salary is due.

Nora: Pooh! we can borrow until then.

Helmer: Nora! (Goes up to her and takes her playfully by the ear.) The same little featherhead! Suppose, now, that I borrowed fifty pounds to-day, and you spent it all in the Christmas week, and then on New Year’s Eve a slate fell on my head and killed me, and—

Nora (putting her hands over his mouth): Oh! don’t say such horrid things.

Helmer: Still, suppose that happened,—what then?

Nora: If that were to happen, I don’t suppose I should care whether I owed money or not.

Helmer: Yes, but what about the people who had lent it?

Nora: They? Who would bother about them? I should not know who they were.

2

Helmer: That is like a woman! But seriously, Nora, you know what I think about that. No debt, no borrowing. There can be no freedom or beauty about a home life that depends on borrowing and debt. We two have kept bravely on the straight road so far, and we will go on the same way for the short time longer that there need be any struggle.

Nora (moving towards the stove): As you please, Torvald.

Helmer (following her): Come, come, my little skylark must not droop her wings. What is this! Is my little squirrel out of temper? (Taking out his purse.) Nora, what do you think I have got here?

Nora (turning round quickly): Money!

Helmer: There you are. (Gives her some money.) Do you think I don’t know what a lot is wanted for housekeeping at Christmas-time?

Nora (counting): Ten shillings—a pound—two pounds! Thank you, thank you, Torvald; that will keep me going for a long time.

Helmer: Indeed it must.

3

Nora: Yes, yes, it will. But come here and let me show you what I have bought. And all so cheap! Look, here is a new suit for Ivar, and a sword; and a horse and a trumpet for Bob; and a doll and dolly’s bedstead for Emmy,—they are very plain, but anyway she will soon break them in pieces. And here are dress- lengths and handkerchiefs for the maids; old Anne ought really to have something better.

Helmer: And what is in this parcel?

Nora (crying out): No, no! you mustn’t see that until this evening.

Helmer: Very well. But now tell me, you extravagant little person, what would you like for yourself?

Nora: For myself? Oh, I am sure I don’t want anything.

Helmer: Yes, but you must. Tell me something reasonable that you would particularly like to have.

Nora: No, I really can’t think of anything—unless, Torvald—

Helmer: Well?

Nora (playing with his coat buttons, and without raising her eyes to his): If you really want to give me something, you might—you might—

Helmer: Well, out with it!

Nora (speaking quickly): You might give me money, Torvald. Only just as much as you can afford; and then one of these days I will buy something with it.

Helmer: But, Nora—

Nora: Oh, do! dear Torvald; please, please do! Then I will wrap it up in beautiful gilt paper and hang it on the Christmas Tree. Wouldn’t that be fun?

Helmer: What are little people called that are always wasting money?

Nora: Spendthrifts—I know. Let us do as you suggest, Torvald, and then I shall have time to think what I am most in want of. That is a very sensible plan, isn’t it?

4

Helmer (smiling): Indeed it is—that is to say, if you were really to save out of the money I give you, and then really buy something for yourself. But if you spend it all on the housekeeping and any number of unnecessary things, then I merely have to pay up again.

Nora: Oh but, Torvald—

Helmer: You can’t deny it, my dear little Nora. (Puts his arm round her waist.) It’s a sweet little spendthrift, but she uses up a deal of money. One would hardly believe how expensive such little persons are!

Nora: It’s a shame to say that. I do really save all I can.

Helmer (laughing): That’s very true,—all you can. But you can’t save anything!

Nora (smiling quietly and happily): You haven’t any idea how many expenses we skylarks and squirrels have, Torvald.

From A Doll’s House: And Two Other Plays by Henrik Ibsen. Translated by R. Farquharson Sharp. E.P. Dutton & Co., 1920.