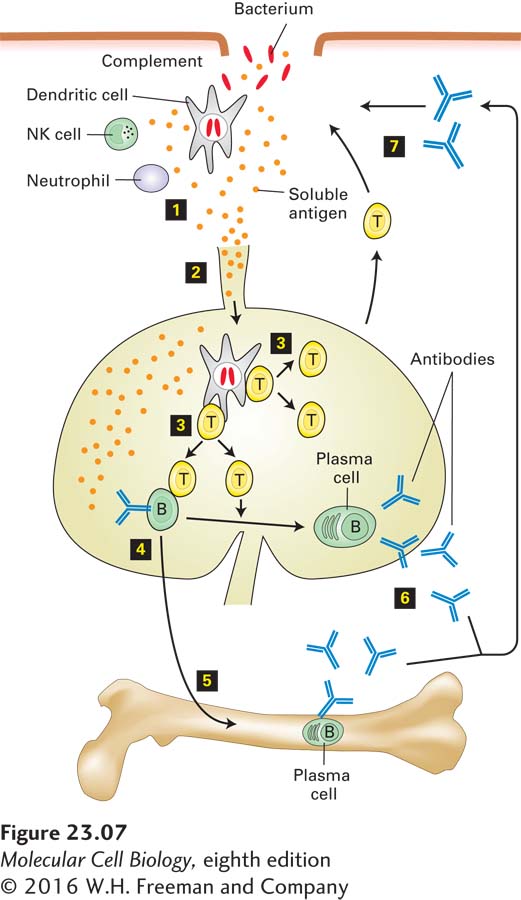

FIGURE 23- e- n- n- n- e-