Vaccines Elicit Protective Immunity Against a Variety of Pathogens

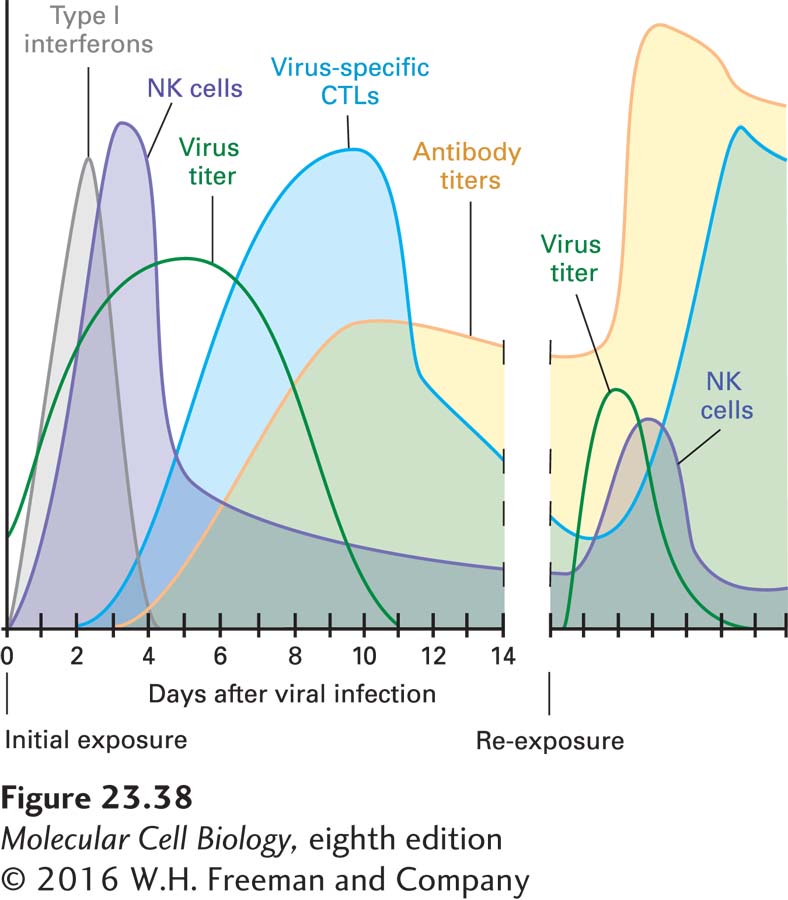

![]() Arguably the most important practical application of immunological principles is vaccines. Vaccines are materials that are designed to be innocuous but that can elicit an immune response for the purpose of providing protection against a challenge with the virulent version of a pathogen (Figure 23-38). It is not always known why vaccines are as successful as they are, but in many cases, the ability to raise antibodies that can neutralize a pathogen (viruses) or that show microbicidal effects (bacteria) are good indicators of successful vaccination.

Arguably the most important practical application of immunological principles is vaccines. Vaccines are materials that are designed to be innocuous but that can elicit an immune response for the purpose of providing protection against a challenge with the virulent version of a pathogen (Figure 23-38). It is not always known why vaccines are as successful as they are, but in many cases, the ability to raise antibodies that can neutralize a pathogen (viruses) or that show microbicidal effects (bacteria) are good indicators of successful vaccination.

Several strategies can lead to a successful vaccine. Serial passage of a pathogen in tissue culture or from animal to animal often leads to attenuation, the molecular basis for which is not well understood. Vaccines may be composed of live attenuated variants of more virulent pathogens. The attenuated version of the pathogen causes a mild form of the disease or causes no symptoms at all. However, by recruiting all the component parts of the adaptive immune system, such live attenuated vaccines can elicit protective levels of antibodies. These antibody levels may wane with advancing age because the lymphocytes responsible for immunological memory may have a finite life span, so repeated immunizations (booster injections) are often required to maintain full protection. Live attenuated vaccines are in use against flu, measles, mumps, and tuberculosis. In the latter case, an attenuated strain of the mycobacterium that causes the disease is used (Bacille Calmette-

Vaccines based on the cowpox virus, a close relative of the human variola virus that causes smallpox, have been used successfully to eradicate smallpox, the first such example of the elimination of an infectious disease. Attempts to achieve a similar feat for polio are nearing completion, but socioeconomic and political factors or armed conflict often complicate the administration of vaccines, leading to reemergence of the disease, as seen recently in Asia.

The other major type of vaccine is called a subunit vaccine. Rather than live attenuated strains of a virulent bacterium or virus, only one or several of its components (a subunit of the entire pathogen) are used to elicit immunity. In certain cases, this approach is sufficient to afford lasting protection against a challenge with the live, virulent source of the antigen used for vaccination. It has been successful in preventing infections with the hepatitis B virus. The commonly used flu vaccines are composed mainly of the envelope proteins neuraminidase and hemagglutinin (see Figure 3-11); these vaccines elicit neutralizing antibodies. For the vaccine against human papillomavirus HPV 16, a serotype that causes cervical cancer, viruslike particles composed of the virus’s capsid structural proteins but devoid of its genetic material are generated; these particles are noninfectious, yet in many respects mimic the intact virion. The HPV vaccine now licensed for use in humans is expected to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer in susceptible populations by perhaps as much as 80 percent, the first example of a vaccine that prevents a particular type of cancer.

Page 1131

From a public health perspective, cheaply produced and widely distributed vaccines are formidable tools for preventing or even eradicating communicable diseases. Current efforts are aimed at producing vaccines against diseases for which no other suitable therapies are available (Ebola virus) or where socioeconomic conditions have made the distribution of drugs problematic (malaria, HIV). With a more complete understanding of how the immune system operates, it should be possible to improve on the design of existing vaccines and extend these principles to diseases for which no successful vaccines are currently available. A remaining challenge is the massive genetic variation that pathogens can acquire: the error-