10-5 Stabilization Policy

Fluctuations in the economy as a whole come from changes in aggregate supply or aggregate demand. Economists call exogenous events that shift these curves shocks to the economy. A shock that shifts the aggregate demand curve is called a demand shock, and a shock that shifts the aggregate supply curve is called a supply shock. These shocks disrupt the economy by pushing output and employment away from their natural levels. One goal of the model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand is to show how shocks cause economic fluctuations.

Another goal of the model is to evaluate how macroeconomic policy can respond to these shocks. Economists use the term stabilization policy to refer to policy actions aimed at reducing the severity of short-run economic fluctuations. Because output and employment fluctuate around their long-run natural levels, stabilization policy dampens the business cycle by keeping output and employment as close to their natural levels as possible.

In the coming chapters, we examine in detail how stabilization policy works and what practical problems arise in its use. Here we begin our analysis of stabilization policy using our simplified version of the model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. In particular, we examine how monetary policy might respond to shocks. Monetary policy is an important component of stabilization policy because, as we have seen, the money supply has a powerful impact on aggregate demand.

Shocks to Aggregate Demand

Consider an example of a demand shock: the introduction and expanded availability of credit cards. Because credit cards are often a more convenient way to make purchases than using cash, they reduce the quantity of money that people choose to hold. This reduction in money demand is equivalent to an increase in the velocity of money. When each person holds less money, the money demand parameter k falls. This means that each dollar of money moves from hand to hand more quickly, so velocity V (= 1/k) rises.

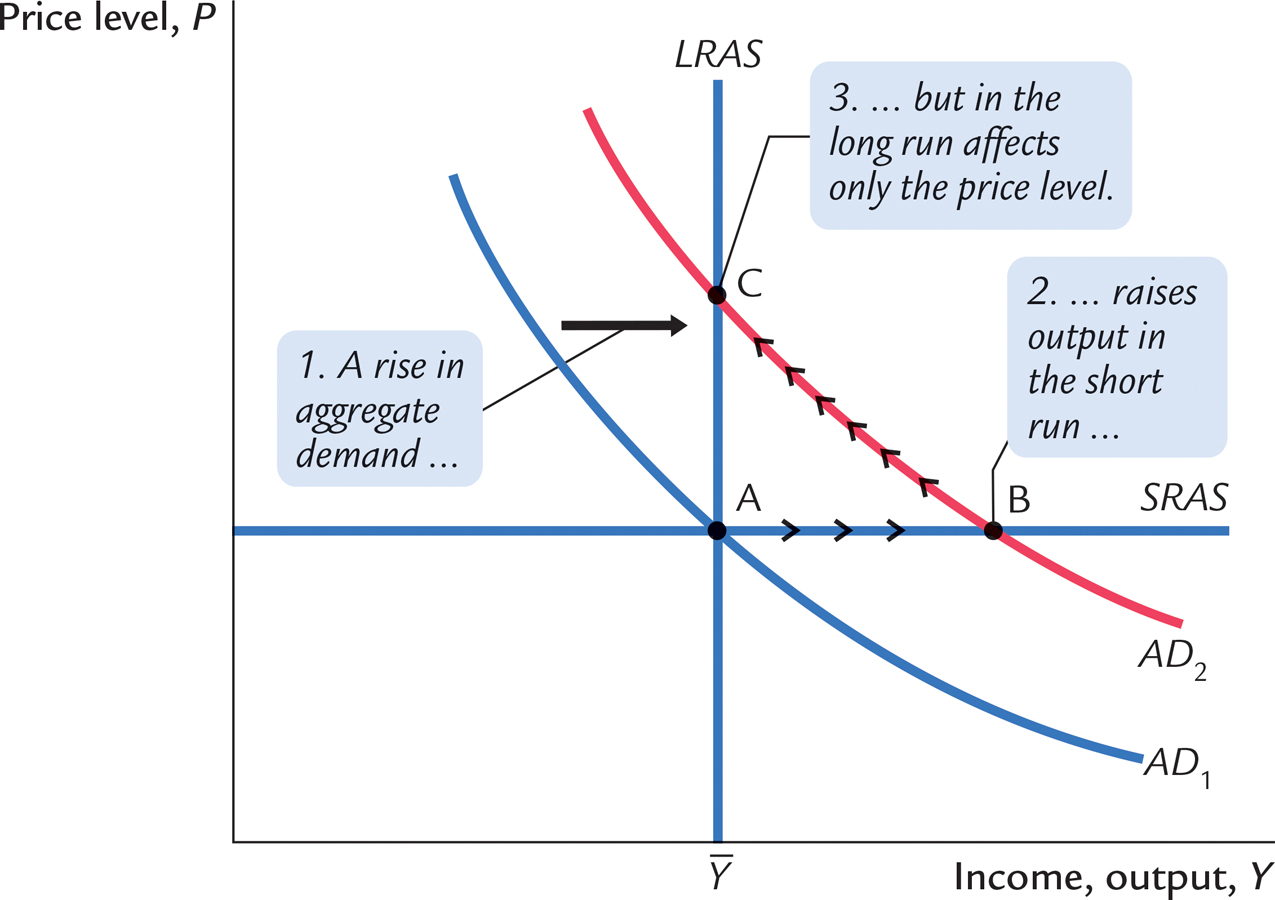

If the money supply is held constant, the increase in velocity causes nominal spending to rise and the aggregate demand curve to shift outward, as in Figure 10-13. In the short run, the increase in demand raises the output of the economy—it causes an economic boom. At the old prices, firms now sell more output. Therefore, they hire more workers, ask their existing workers to work longer hours, and make greater use of their factories and equipment.

FIGURE 10-13

Over time, the high level of aggregate demand pulls up wages and prices. As the price level rises, the quantity of output demanded declines, and the economy gradually approaches the natural level of production. But during the transition to the higher price level, the economy’s output is higher than its natural level.

What can the Fed do to dampen this boom and keep output closer to the natural level? The Fed might reduce the money supply to offset the increase in velocity. Offsetting the change in velocity would stabilize aggregate demand. Thus, the Fed can reduce or even eliminate the impact of demand shocks on output and employment if it can skillfully control the money supply. Whether the Fed in fact has the necessary skill is a more difficult question, which we take up in Chapter 18.

303

Shocks to Aggregate Supply

Shocks to aggregate supply can also cause economic fluctuations. A supply shock is a shock to the economy that alters the cost of producing goods and services and, as a result, the prices that firms charge. Because supply shocks have a direct impact on the price level, they are sometimes called price shocks. Here are some examples:

A drought that destroys crops. The reduction in food supply pushes up food prices.

A new environmental protection law that requires firms to reduce their emissions of pollutants. Firms pass on the added costs to customers in the form of higher prices.

An increase in union aggressiveness. This pushes up wages and the prices of the goods produced by union workers.

The organization of an international oil cartel. By curtailing competition, the major oil producers can raise the world price of oil.

All these events are adverse supply shocks, which means they push costs and prices upward. A favorable supply shock, such as the breakup of an international oil cartel, reduces costs and prices.

304

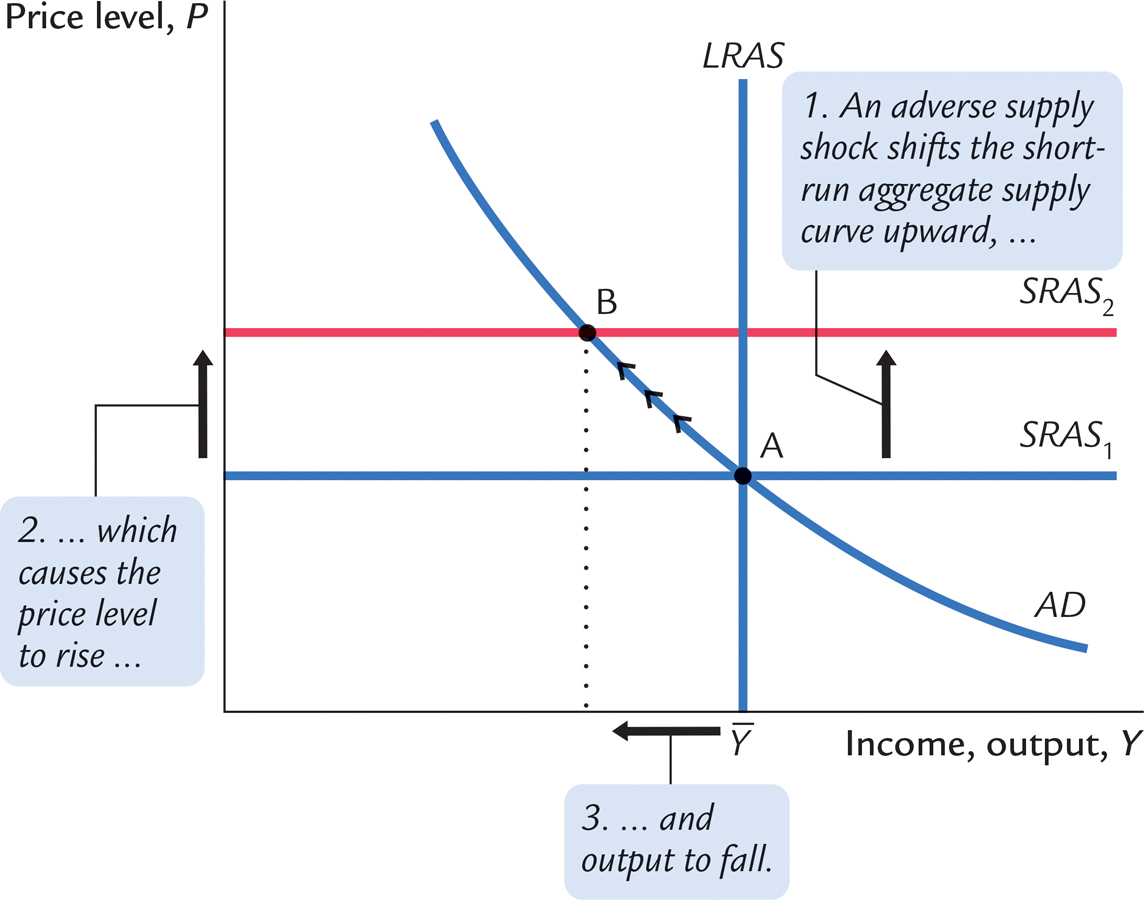

Figure 10-14 shows how an adverse supply shock affects the economy. The short-run aggregate supply curve shifts upward. (The supply shock may also lower the natural level of output and thus shift the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left, but we ignore that effect here.) If aggregate demand is held constant, the economy moves from point A to point B: the price level rises and the amount of output falls below its natural level. An experience like this is called stagflation because it combines economic stagnation (falling output and, from Okun’s law, rising unemployment) with inflation (rising prices).

FIGURE 10-14

Faced with an adverse supply shock, a policymaker with the ability to influence aggregate demand, such as the Fed, has a difficult choice between two options. The first option, implicit in Figure 10-14, is to hold aggregate demand constant. In this case, output and employment are lower than the natural level. Eventually, prices will fall to restore full employment at the old price level (point A), but the cost of this adjustment process is a painful recession.

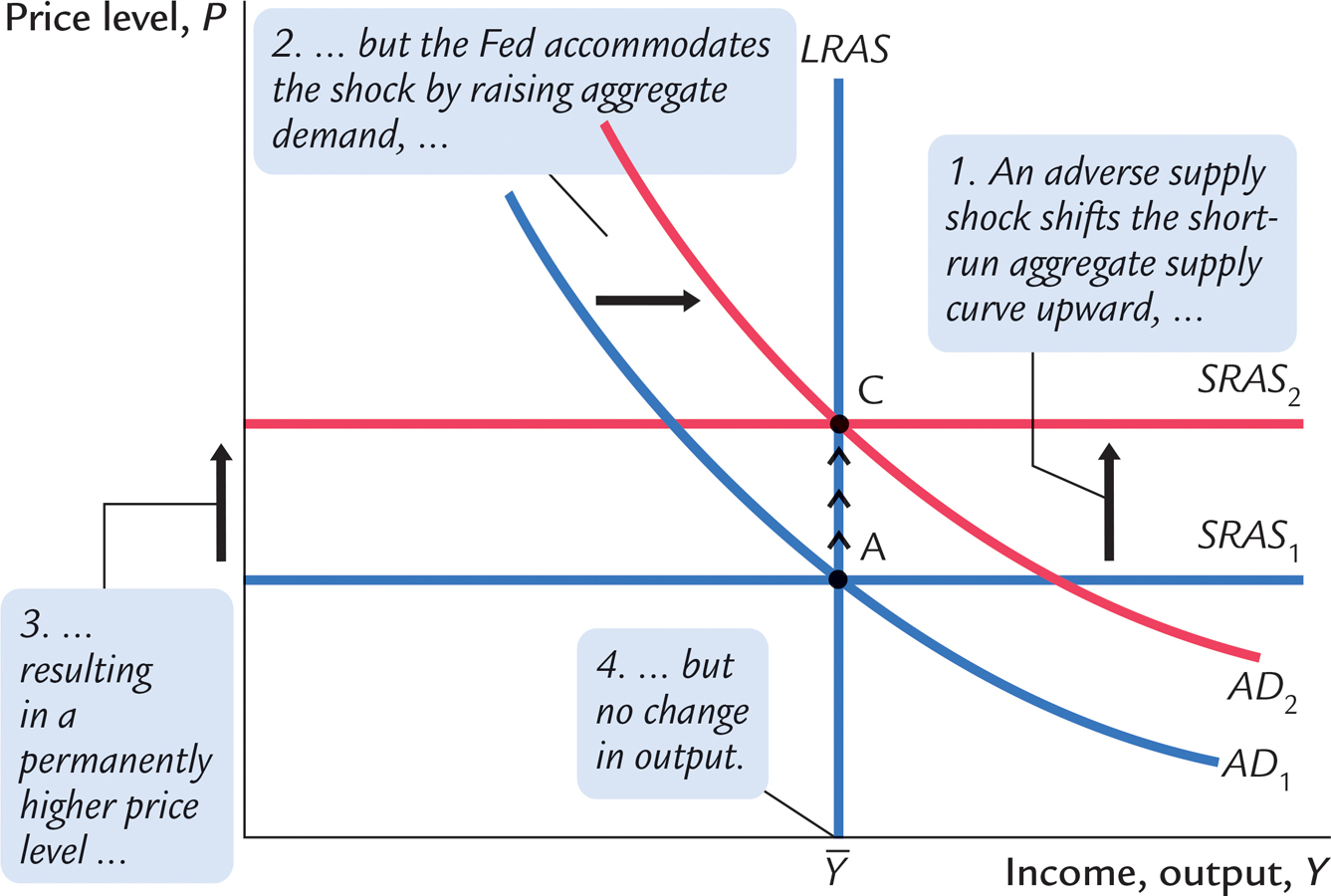

The second option, illustrated in Figure 10-15, is to expand aggregate demand to bring the economy toward the natural level of output more quickly. If the increase in aggregate demand coincides with the shock to aggregate supply, the economy goes immediately from point A to point C. In this case, the Fed is said to accommodate the supply shock. The drawback of this option, of course, is that the price level is permanently higher. There is no way to adjust aggregate demand to maintain full employment and keep the price level stable.

FIGURE 10-15

305

CASE STUDY

How OPEC Helped Cause Stagflation in the 1970s and Euphoria in the 1980s

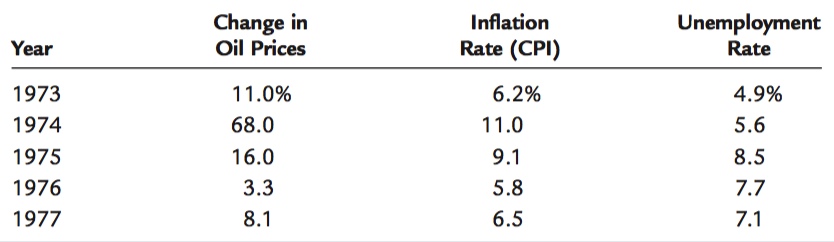

The most disruptive supply shocks in recent history were caused by OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. OPEC is a cartel, which is an organization of suppliers that coordinate production levels and prices. In the early 1970s, OPEC’s reduction in the supply of oil nearly doubled the world price. This increase in oil prices caused stagflation in most industrial countries. These statistics show what happened in the United States:

In 1986 oil prices fell by nearly half. This favorable supply shock led to one of the lowest inflation rates experienced during that era and to falling unemployment.

More recently, OPEC has not been a major cause of economic fluctuations. Conservation efforts and technological changes have made the U.S. economy less susceptible to oil shocks. The economy today is more service-based and less manufacturing-based, and services typically require less energy to produce than do manufactured goods. Because the amount of oil consumed per unit of real GDP has fallen by more than half over the previous three decades, it takes a much larger oil-price change to have the impact on the economy that we observed in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, when oil prices fluctuate substantially, as they have in recent years, these price changes have a smaller macroeconomic impact than they would have had in the past.5

307