13-3 The Small Open Economy Under Fixed Exchange Rates

We now turn to the second type of exchange-rate system: fixed exchange rates. Under a fixed exchange rate, the central bank announces a value for the exchange rate and stands ready to buy and sell the domestic currency to keep the exchange rate at its announced level. This type of system has been used in many historical periods. From 1944 to 1971, most of the world’s major economies, including that of the United States, operated within the Bretton Woods system—an international monetary system under which most governments agreed to fix exchange rates. From 1995 to 2005, China fixed the value of its currency against the U.S. dollar—a policy that, as we will see, was a source of some tension between the two countries.

In this section we discuss how such a system works, and we examine the impact of economic policies on an economy with a fixed exchange rate. Later in the chapter we examine the pros and cons of fixed exchange rates.

378

How a Fixed-Exchange-Rate System Works

Under a system of fixed exchange rates, a central bank stands ready to buy or sell the domestic currency for foreign currencies at a predetermined price. For example, suppose the Fed announced that it was going to fix the yen/dollar exchange rate at 100 yen per dollar. It would then stand ready to give $1 in exchange for 100 yen or to give 100 yen in exchange for $1. To carry out this policy, the Fed would need a reserve of dollars (which it can print) and a reserve of yen (which it must have purchased previously).

A fixed exchange rate dedicates a country’s monetary policy to the single goal of keeping the exchange rate at the announced level. In other words, the essence of a fixed-exchange-rate system is the commitment of the central bank to allow the money supply to adjust to whatever level will ensure that the equilibrium exchange rate in the market for foreign-currency exchange equals the announced exchange rate. Moreover, as long as the central bank stands ready to buy or sell foreign currency at the fixed exchange rate, the money supply adjusts automatically to the necessary level.

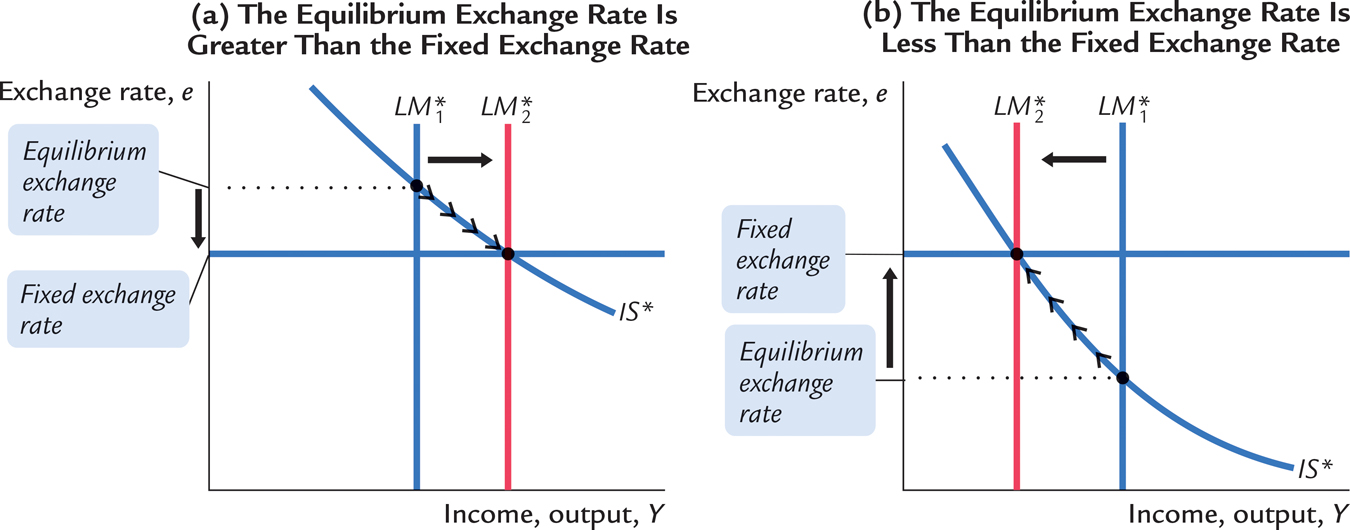

To see how fixing the exchange rate determines the money supply, consider the following example. Suppose the Fed decides to fix the exchange rate at 100 yen per dollar, but, in the current equilibrium with the current money supply, the market exchange rate is 150 yen per dollar. This situation is illustrated in panel (a) of Figure 13-7. Notice that there is a profit opportunity: an arbitrageur could buy 300 yen in the foreign-exchange market for $2 and then sell the yen to the Fed for $3, making a $1 profit. When the Fed buys these yen from the arbitrageur, the dollars it pays for them automatically increase the money supply. The rise in the money supply shifts the LM* curve to the right, lowering the equilibrium exchange rate. In this way, the money supply continues to rise until the equilibrium exchange rate falls to the level the Fed has announced.

FIGURE 13-7

Conversely, suppose that when the Fed decides to fix the exchange rate at 100 yen per dollar, the equilibrium has a market exchange rate of 50 yen per dollar. Panel (b) of Figure 13-7 shows this situation. In this case, an arbitrageur could make a profit by buying 100 yen from the Fed for $1 and then selling the yen in the marketplace for $2. When the Fed sells these yen, the $1 it receives automatically reduces the money supply. The fall in the money supply shifts the LM* curve to the left, raising the equilibrium exchange rate. The money supply continues to fall until the equilibrium exchange rate rises to the announced level.

It is important to understand that this exchange-rate system fixes the nominal exchange rate. Whether it also fixes the real exchange rate depends on the time horizon under consideration. If prices are flexible, as they are in the long run, then the real exchange rate can change even while the nominal exchange rate is fixed. Therefore, in the long run described in Chapter 6, a policy to fix the nominal exchange rate would not influence any real variable, including the real exchange rate. A fixed nominal exchange rate would influence only the money supply and the price level. Yet in the short run described by the Mundell–Fleming model, prices are fixed, so a fixed nominal exchange rate implies a fixed real exchange rate as well.

379

CASE STUDY

The International Gold Standard

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most of the world’s major economies operated under the gold standard. Each country maintained a reserve of gold and agreed to exchange one unit of its currency for a specified amount of gold. Through the gold standard, the world’s economies maintained a system of fixed exchange rates.

To see how an international gold standard fixes exchange rates, suppose that the U.S. Treasury stands ready to buy or sell 1 ounce of gold for $100, and the Bank of England stands ready to buy or sell 1 ounce of gold for 100 pounds. Together, these policies fix the rate of exchange between dollars and pounds: $1 must trade for 1 pound. Otherwise, the law of one price would be violated, and it would be profitable to buy gold in one country and sell it in the other.

For example, suppose that the market exchange rate is 2 pounds per dollar. In this case, an arbitrageur could buy 200 pounds for $100, use the pounds to buy 2 ounces of gold from the Bank of England, bring the gold to the United States, and sell it to the Treasury for $200—making a $100 profit. Moreover, by bringing the gold to the United States from England, the arbitrageur would increase the money supply in the United States and decrease the money supply in England.

380

Thus, during the era of the gold standard, the international transport of gold by arbitrageurs was an automatic mechanism adjusting the money supply and stabilizing exchange rates. This system did not completely fix exchange rates, because shipping gold across the Atlantic was costly. Yet the international gold standard did keep the exchange rate within a range dictated by transportation costs. It thereby prevented large and persistent movements in exchange rates.3

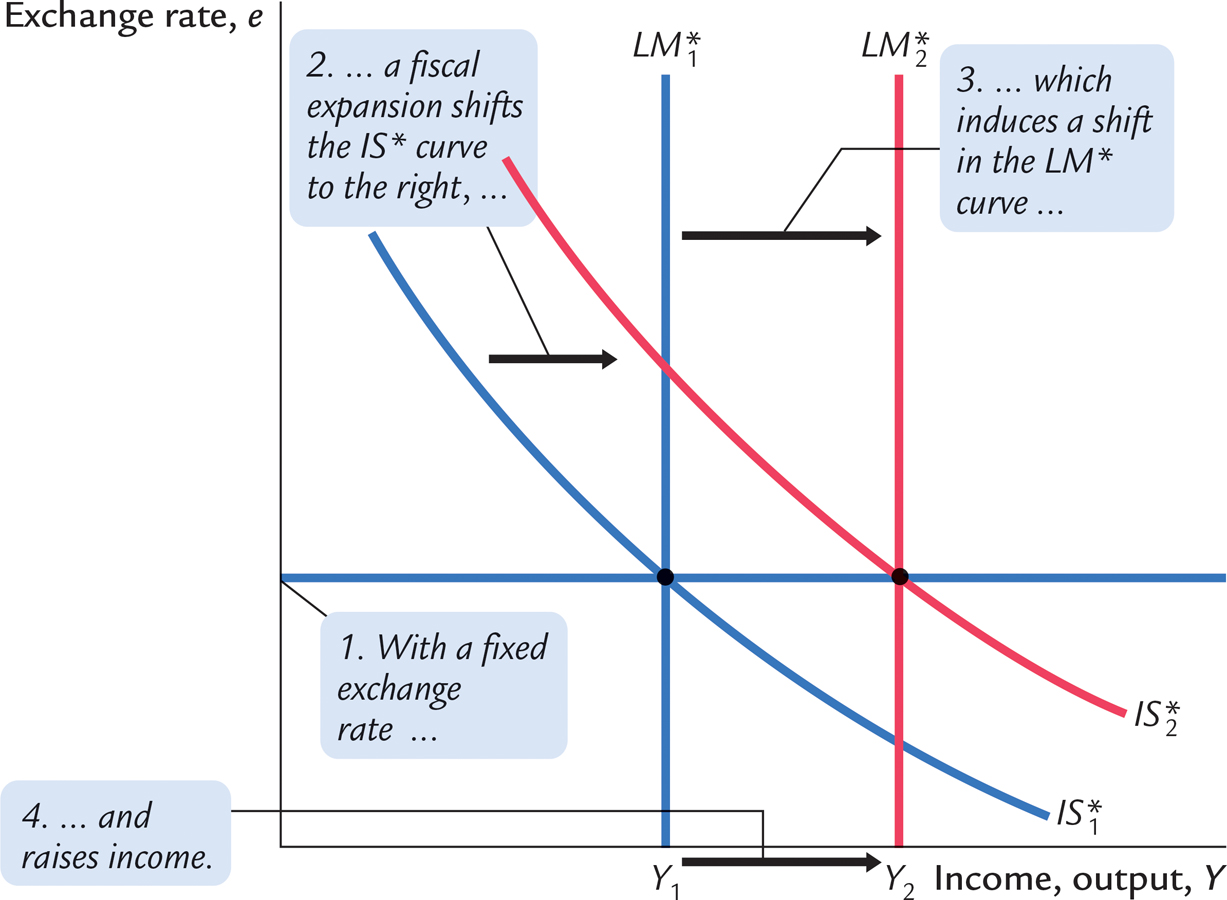

Fiscal Policy

Let’s now examine how economic policies affect a small open economy with a fixed exchange rate. Suppose that the government stimulates domestic spending by increasing government purchases or by cutting taxes. This policy shifts the IS* curve to the right, as in Figure 13-8, putting upward pressure on the market exchange rate. But because the central bank stands ready to trade foreign and domestic currency at the fixed exchange rate, arbitrageurs quickly respond to the rising exchange rate by selling foreign currency to the central bank, leading to an automatic monetary expansion. The rise in the money supply shifts the LM* curve to the right. Thus, under a fixed exchange rate, a fiscal expansion raises aggregate income.

FIGURE 13-8

381

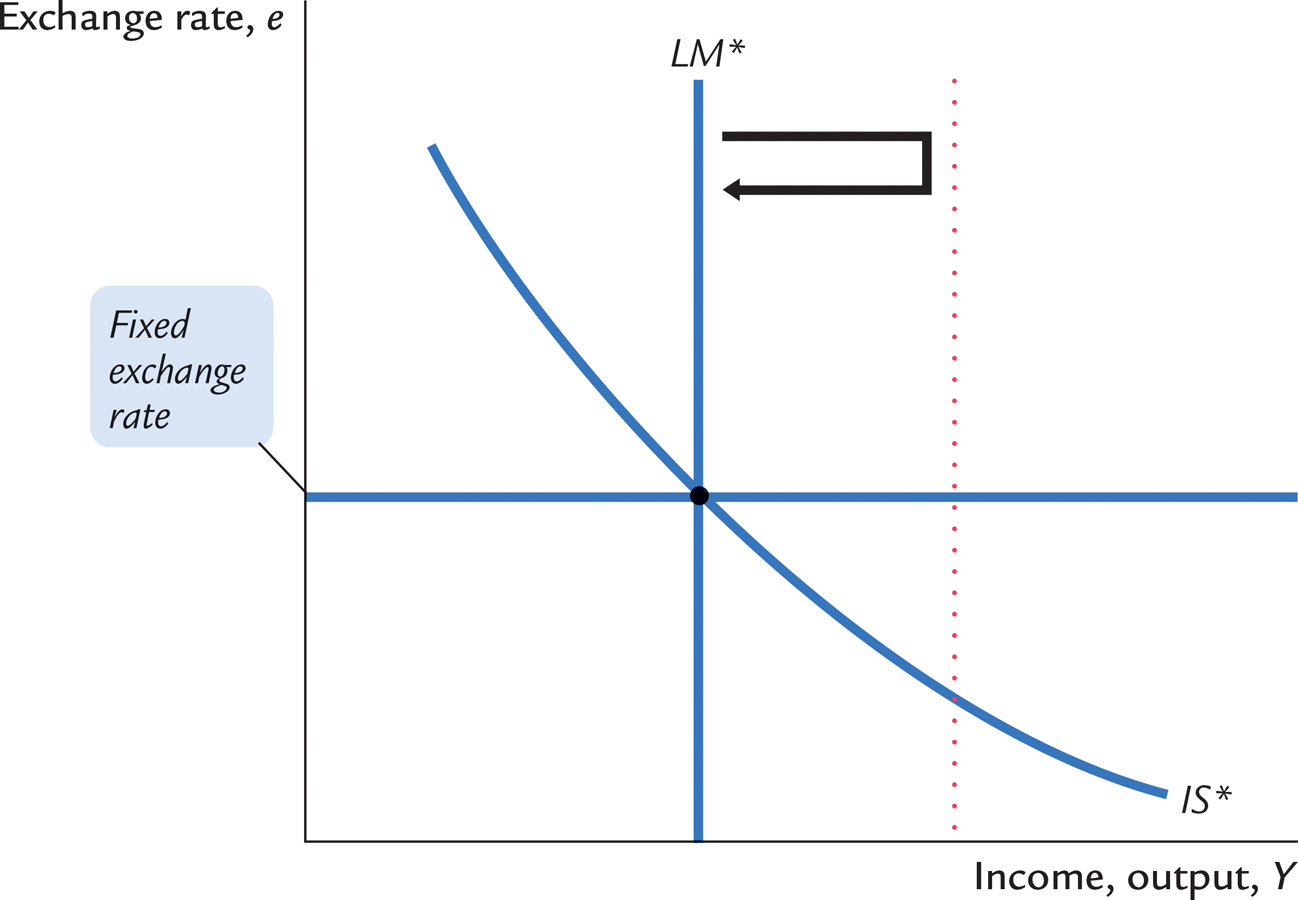

Monetary Policy

Imagine that a central bank operating with a fixed exchange rate tries to increase the money supply—for example, by buying bonds from the public. What would happen? The initial impact of this policy is to shift the LM* curve to the right, lowering the exchange rate, as in Figure 13-9. But, because the central bank is committed to trading foreign and domestic currency at a fixed exchange rate, arbitrageurs quickly respond to the falling exchange rate by selling the domestic currency to the central bank, causing the money supply and the LM* curve to return to their initial positions. Hence, monetary policy as usually conducted is ineffectual under a fixed exchange rate. By agreeing to fix the exchange rate, the central bank gives up its control over the money supply.

FIGURE 13-9

A country with a fixed exchange rate can, however, conduct a type of monetary policy: it can decide to change the level at which the exchange rate is fixed. A reduction in the official value of the currency is called a devaluation, and an increase in its official value is called a revaluation. In the Mundell–Fleming model, a devaluation shifts the LM* curve to the right; it acts like an increase in the money supply under a floating exchange rate. A devaluation thus expands net exports and raises aggregate income. Conversely, a revaluation shifts the LM* curve to the left, reduces net exports, and lowers aggregate income.

382

CASE STUDY

Devaluation and the Recovery from the Great Depression

The Great Depression of the 1930s was a global problem. Although events in the United States may have precipitated the downturn, all of the world’s major economies experienced huge declines in production and employment. Yet not all governments responded to this calamity in the same way.

One key difference among governments was how committed they were to the fixed exchange rate set by the international gold standard. Some countries, such as France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, maintained the old rate of exchange between gold and currency. Other countries, such as Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, reduced the amount of gold they would pay for each unit of currency by about 50 percent. By reducing the gold content of their currencies, these governments devalued their currencies relative to those of other countries.

The subsequent experience of these two groups of countries confirms the prediction of the Mundell–Fleming model. Those countries that pursued a policy of devaluation recovered quickly from the Depression. The lower value of the currency raised the money supply, stimulated exports, and expanded production. By contrast, those countries that maintained the old exchange rate suffered longer with a depressed level of economic activity.

What about the United States? President Herbert Hoover kept the United States on the gold standard, but in a controversial move, President Franklin Roosevelt took the nation off it in June 1933, just three months after taking office. That date roughly coincides with the end of the deflation and the beginning of recovery. Many economic historians believe that removing the nation from the gold standard was the most significant policy action that President Roosevelt took to end the Great Depression.4

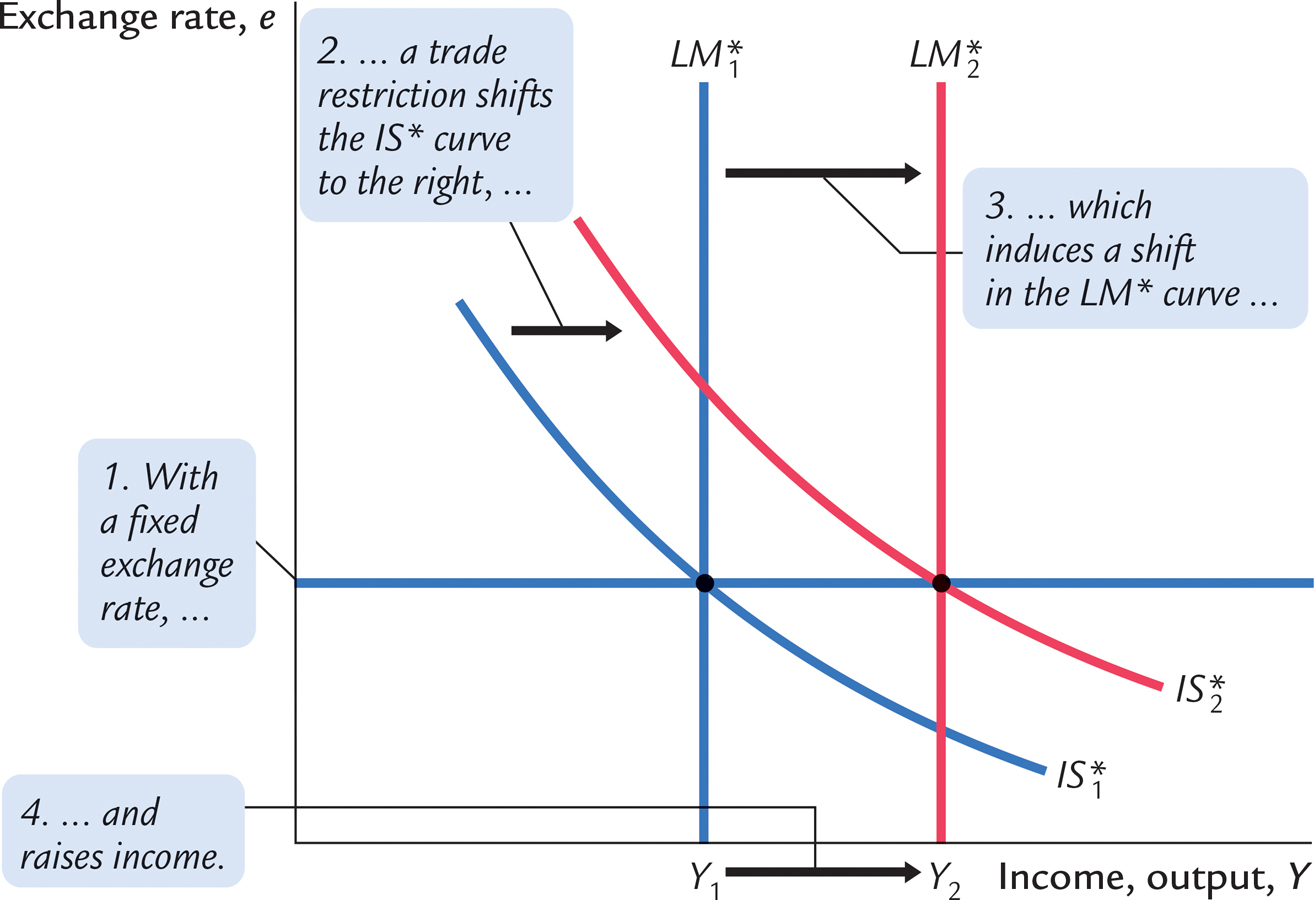

Trade Policy

Suppose that the government reduces imports by imposing an import quota or a tariff. This policy shifts the net-exports schedule to the right and thus shifts the IS* curve to the right, as in Figure 13-10. The shift in the IS* curve tends to raise the exchange rate. To keep the exchange rate at the fixed level, the money supply must rise, shifting the LM* curve to the right.

FIGURE 13-10

The result of a trade restriction under a fixed exchange rate is very different from that under a floating exchange rate. In both cases, a trade restriction shifts the net-exports schedule to the right, but only under a fixed exchange rate does a trade restriction increase net exports NX. The reason is that a trade restriction under a fixed exchange rate induces monetary expansion rather than an appreciation of the currency. The monetary expansion, in turn, raises aggregate income. Recall the accounting identity

383

NX = S − I.

When income rises, saving also rises, and this implies an increase in net exports.

Policy in the Mundell–Fleming Model: A Summary

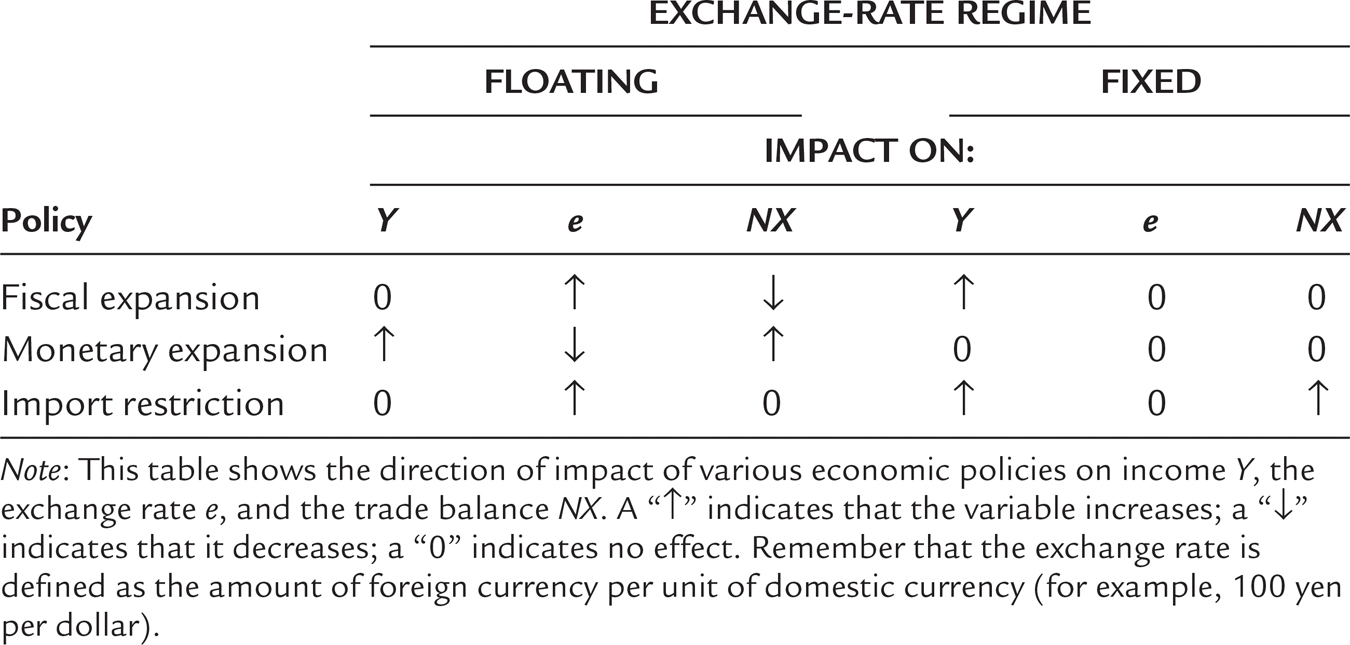

The Mundell–Fleming model shows that the effect of almost any economic policy on a small open economy depends on whether the exchange rate is floating or fixed. Table 13-1 summarizes our analysis of the short-run effects of fiscal, monetary, and trade policies on income, the exchange rate, and the trade balance. What is most striking is that all of the results are different under floating and fixed exchange rates.

TABLE 13-1

TABLE 13-1: The Mundell–Fleming Model: Summary of Policy Effect

To be more specific, the Mundell–Fleming model shows that the power of monetary and fiscal policy to influence aggregate income depends on the exchange-rate regime. Under floating exchange rates, only monetary policy can affect income. The usual expansionary impact of fiscal policy is offset by a rise in the value of the currency and a decrease in net exports. Under fixed exchange rates, only fiscal policy can affect income. The normal potency of monetary policy is lost because the money supply is dedicated to maintaining the exchange rate at the announced level.

384