15-4 Two Applications: Lessons for Monetary Policy

So far in this chapter, we have assembled a dynamic model of inflation and output and used it to show how various shocks affect the time paths of output, inflation, and interest rates. We now use the model to shed light on the design of monetary policy.

It is worth pausing at this point to consider what we mean by “the design of monetary policy.” So far in this analysis, the central bank has had a simple role: it merely had to adjust the money supply to ensure that the nominal interest rate hit the target level prescribed by the monetary-policy rule. The two key parameters of that policy rule are θπ (the responsiveness of the target interest rate to inflation) and θY (the responsiveness of the target interest rate to output). We have taken these parameters as given without discussing how they are chosen. Now that we know how the model works, we can consider a deeper question: What should the parameters of the monetary policy rule be?

464

The Tradeoff Between Output Variability and Inflation Variability

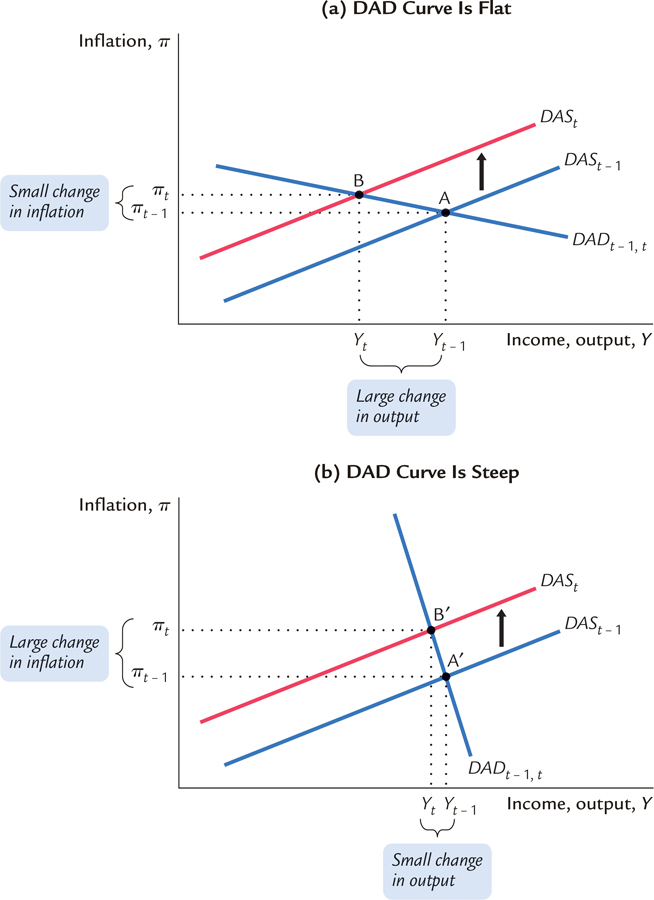

Consider the impact of a supply shock on output and inflation. According to the dynamic AD–AS model, the impact of this shock depends crucially on the slope of the dynamic aggregate demand curve. In particular, the slope of the DAD curve determines whether a supply shock has a large or small impact on output and inflation.

This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 15-12. In the two panels of this figure, the economy experiences the same supply shock. In panel (a), the dynamic aggregate demand curve is nearly flat, so the shock has a small effect on inflation but a large effect on output. In panel (b), the dynamic aggregate demand curve is steep, so the shock has a large effect on inflation but a small effect on output.

FIGURE 15-12

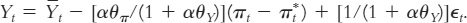

Why is this important for monetary policy? Because the central bank can influence the slope of the dynamic aggregate demand curve. Recall the equation for the DAD curve:

Two key parameters here are θπ and θY, which govern how much the central bank’s interest rate target responds to changes in inflation and output. When the central bank chooses these policy parameters, it determines the slope of the DAD curve and thus the economy’s short-run response to supply shocks.

On the one hand, suppose that, when setting the interest rate, the central bank responds strongly to inflation (θπ is large) and weakly to output (θY is small). In this case, the coefficient on inflation in the above equation is large. That is, a small change in inflation has a large effect on output. As a result, the dynamic aggregate demand curve is relatively flat, and supply shocks have large effects on output but small effects on inflation. The story goes like this: When the economy experiences a supply shock that pushes up inflation, the central bank’s policy rule has it respond vigorously with higher interest rates. Sharply higher interest rates significantly reduce the quantity of goods and services demanded, thereby leading to a large recession that dampens the inflationary impact of the shock (which was the purpose of the monetary policy response).

On the other hand, suppose that, when setting the interest rate, the central bank responds weakly to inflation (θπ is small) but strongly to output (θY is large). In this case, the coefficient on inflation in the above equation is small, which means that even a large change in inflation has only a small effect on output. As a result, the dynamic aggregate demand curve is relatively steep, and supply shocks have small effects on output but large effects on inflation. The story is just the opposite as before: Now, when the economy experiences a supply shock that pushes up inflation, the central bank’s policy rule has it respond with only slightly higher interest rates. This small policy response avoids a large recession but accommodates the inflationary shock.

465

In its choice of monetary policy, the central bank determines which of these two scenarios will play out. That is, when setting the policy parameters θπ and θY, the central bank chooses whether to make the economy look more like panel (a) or more like panel (b) of Figure 15-12. When making this choice, the central bank faces a tradeoff between output variability and inflation variability. The central bank can be a hard-line inflation fighter, as in panel (a), in which case inflation is stable but output is volatile. Alternatively, it can be more accommodative, as in panel (b), in which case inflation is volatile but output is more stable. It can also choose some position in between these two extremes.

466

One job of a central bank is to promote economic stability. There are, however, various dimensions to this goal. When there are tradeoffs to be made, the central bank has to determine what kind of stability to pursue. The dynamic AD–AS model shows that one fundamental tradeoff is between the variability in inflation and the variability in output.

Note that this tradeoff is very different from a simple tradeoff between inflation and output. In the long run of this model, inflation goes to its target, and output goes to its natural level. Consistent with classical macroeconomic theory, policymakers do not face a long-run tradeoff between inflation and output. Instead, they face a choice about which of these two measures of macroeconomic performance they want to stabilize. When deciding on the parameters of the monetary-policy rule, they determine whether supply shocks lead to inflation variability, output variability, or some combination of the two.

CASE STUDY

Different Mandates, Different Realities: The Fed Versus the ECB

According to the dynamic AD–AS model, a key policy choice facing any central bank concerns the parameters of its policy rule. The monetary parameters θπ and θY determine how much the interest rate responds to macroeconomic conditions. As we have just seen, these responses in turn determine the volatility of inflation and output.

The U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) appear to have different approaches to this decision. The legislation that created the Fed states explicitly that its goal is “to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Because the Fed is supposed to stabilize both employment and prices, it is said to have a dual mandate. (The third goal—moderate long-term interest rates—should follow naturally from stable prices.) By contrast, the ECB says on its Web site that “the primary objective of the ECB’s monetary policy is to maintain price stability. The ECB aims at inflation rates of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.” All other macroeconomic goals, including stability of output and employment, appear to be secondary.

We can interpret these differences in light of our model. Compared to the Fed, the ECB seems to give more weight to inflation stability and less weight to output stability. This difference in objectives should be reflected in the parameters of the monetary-policy rules. To achieve its dual mandate, the Fed would respond more to output and less to inflation than the ECB would.

The financial crisis of 2008–2009 illustrates these differences. In 2008, the world economy was experiencing rising oil prices, a financial crisis, and a slowdown in economic activity. The Fed responded to these events by lowering its target interest rate from 4.25 percent at the beginning of the year to a range of 0 to 0.25 percent at year’s end. The ECB, facing a similar situation, also cut interest rates, but by much less—from 3 percent to 2 percent. It cut the interest rate to 0.25 percent only in 2009, when the depth of the recession was clear and inflationary worries had subsided. Throughout this episode, the ECB was less concerned about recession and more concerned about keeping inflation in check.

467

Although the dynamic AD–AS model predicts that, other things equal, the policy of the ECB should lead to more variable output and more stable inflation, testing this prediction is difficult. In practice, other things are rarely equal. Europe and the United States differ in many ways beyond the policies of their central banks. For example, in 2010, several European nations, most notably Greece, came close to defaulting on their government debt. This Eurozone crisis reduced confidence and aggregate demand around the world, but the impact was much larger on Europe than on the United States.

As this book was going to press in late 2014, the two central banks faced very different situations. In the United States, unemployment had fallen considerably since the Great Recession of 2008–2009, and inflation was only slightly below the Fed’s 2-percent target. By contrast, in Europe, unemployment remained high, and inflation was running less than 0.5 percent. With interest rates at the zero lower bound, ECB President Mario Draghi was struggling to find ways to increase aggregate demand and pull European inflation up to its target.

The Taylor Principle

How much should the nominal interest rate set by the central bank respond to changes in inflation? The dynamic AD–AS model does not give a definitive answer, but it does offer an important guideline.

Recall the equation for monetary policy:

where θπ and θY are parameters that measure how much the interest rate set by the central bank responds to inflation and output. In particular, according to this equation, a 1-percentage-point increase in inflation πt induces an increase in the nominal interest rate it of 1 + θπ percentage points. Because we assume that θπ is greater than zero, whenever inflation increases, the central bank raises the nominal interest rate by an even larger amount.

The assumption that θπ > 0 has important implications for the behavior of the real interest rate. Recall that the real interest rate is rt = it − Etπt+1. With our assumption of adaptive expectations, it can also be written as rt = it − πt. As a result, if an increase in inflation πt leads to a greater increase in the nominal interest rate it, it leads to an increase in the real interest rate rt as well. As you may recall from earlier in this chapter, this fact was a key part of our explanation for why the dynamic aggregate demand curve slopes downward.

Imagine, however, that the central bank behaved differently and, instead, increased the nominal interest rate by less than the increase in inflation. In this case, the monetary policy parameter θπ would be less than zero. This change would profoundly alter the model. Recall that the dynamic aggregate demand equation is:

468

If θπ is negative, then an increase in inflation increases the quantity of output demanded. To understand why, keep in mind what is happening to the real interest rate. If an increase in inflation leads to a smaller increase in the nominal interest rate (because θπ < 0), then the real interest rate decreases. The lower real interest rate reduces the cost of borrowing, which in turn increases the quantity of goods and services demanded. Thus, a negative value of θπ means the dynamic aggregate demand curve slopes upward.

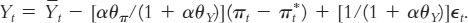

An economy with θπ < 0 and an upward-sloping DAD curve can run into some serious problems. In particular, inflation can become unstable. Suppose, for example, there is a positive shock to aggregate demand that lasts for only a single period. Normally, such an event would have only a temporary effect on the economy, and the inflation rate would over time return to its target (similar to the analysis illustrated in Figure 15-9). If θπ < 0, however, events unfold very differently:

The positive demand shock increases output and inflation in the period in which it occurs.

Because expectations are determined adaptively, higher inflation increases expected inflation.

Because firms set their prices based in part on expected inflation, higher expected inflation leads to higher actual inflation in subsequent periods (even after the demand shock has dissipated).

Higher inflation causes the central bank to raise the nominal interest rate. But because θπ < 0, the central bank increases the nominal interest rate by less than the increase in inflation, so the real interest rate declines.

The lower real interest rate increases the quantity of goods and services demanded above the natural level of output.

With output above its natural level, firms face higher marginal costs, and inflation rises yet again.

The economy returns to step 2.

The economy finds itself in a vicious circle of ever-higher inflation and expected inflation. Inflation spirals out of control.

Figure 15-13 illustrates this process. Suppose that in period t there is a one-time positive shock to aggregate demand. That is, for one period only, the dynamic aggregate demand curve shifts to the right, to DADt; in the next period, it returns to its original position. In period t, the economy moves from point A to point B. Output and inflation rise. In the next period, because higher inflation has increased expected inflation, the dynamic aggregate supply curve shifts upward, to DASt+1. The economy moves from point B to point C. But because the dynamic aggregate demand curve is now upward sloping, output remains above its natural level, even though demand shock has disappeared. Thus, inflation rises yet again, shifting the DAS curve farther upward in the next period, moving the economy to point D. And so on. Inflation continues to rise with no end in sight.

FIGURE 15-13

469

The dynamic AD–AS model leads to a strong conclusion: For inflation to be stable, the central bank must respond to an increase in inflation with an even greater increase in the nominal interest rate. This conclusion is sometimes called the Taylor principle, after economist John Taylor, who emphasized its importance in the design of monetary policy. (As we saw earlier, in his proposed Taylor rule, Taylor suggested that θπ should equal 0.5). Most of our analysis in this chapter assumed that the Taylor principle holds; that is, we assumed that θπ > 0. We can see now that there is good reason for a central bank to adhere to this guideline.

470

CASE STUDY

What Caused the Great Inflation?

In the 1970s, inflation in the United States got out of hand. As we saw in previous chapters, the inflation rate during this decade reached double-digit levels. Rising prices were widely considered the major economic problem of the time. In 1979, Paul Volcker, the recently appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve, announced a change in monetary policy that eventually brought inflation back under control. Volcker and his successor, Alan Greenspan, then presided over low and stable inflation for the next quarter century.

The dynamic AD–AS model offers a new perspective on these events. According to research by monetary economists Richard Clarida, Jordi Gali, and Mark Gertler, the key is the Taylor principle. Clarida and colleagues examined the data on interest rates, output, and inflation and estimated the parameters of the monetary-policy rule. They found that the Volcker–Greenspan monetary policy obeyed the Taylor principle, whereas earlier monetary policy did not. In particular, the parameter θπ (which measures the responsiveness of interest rates to inflation in the monetary-policy rule) was estimated to be 0.72 during the Volcker–Greenspan regime after 1979, close to Taylor’s proposed value of 0.5, but it was −0.14 during the pre-Volcker era from 1960 to 1978.2 The negative value of θπ during the pre-Volcker era means that monetary policy did not satisfy the Taylor principle. In other words, the pre-Volcker Fed was not responding strongly enough to inflation.

This finding suggests a potential cause of the great inflation of the 1970s. When the U.S. economy was hit by demand shocks (such as government spending on the Vietnam War) and supply shocks (such as the OPEC oil-price increases), the Fed raised the nominal interest rate in response to rising inflation but not by enough. Therefore, despite the increase in the nominal interest rate, the real interest rate fell. This insufficient monetary response failed to squash the inflation that arose from these shocks. Indeed, the decline in the real interest rate increased the quantity of goods and services demanded, thereby exacerbating the inflationary pressures. The problem of spiraling inflation was not solved until the monetary-policy rule was changed to include a more vigorous response of interest rates to inflation.

An open question is why policymakers were so passive in the earlier era. Here are some conjectures from Clarida, Gali, and Gertler:

Why is it that during the pre-1979 period the Federal Reserve followed a rule that was clearly inferior? Another way to look at the issue is to ask why it is that the Fed maintained persistently low short-term real rates in the face of high or rising inflation. One possibility … is that the Fed thought the natural rate of unemployment at this time was much lower than it really was (or equivalently, that the output gap was much smaller)….

471

Another somewhat related possibility is that, at that time, neither the Fed nor the economics profession understood the dynamics of inflation very well. Indeed, it was not until the mid-to-late 1970s that intermediate textbooks began emphasizing the absence of a long-run trade-off between inflation and output. The ideas that expectations may matter in generating inflation and that credibility is important in policymaking were simply not well established during that era. What all this suggests is that in understanding historical economic behavior, it is important to take into account the state of policymakers’ knowledge of the economy and how it may have evolved over time.