National Income: Where It Comes From and Where It Goes

47

A large income is the best recipe for happiness I ever heard of.

—Jane Austen

The most important macroeconomic variable is gross domestic product (GDP). As we have seen, GDP measures both a nation’s total output of goods and services and its total income. To appreciate the significance of GDP, one need only take a quick look at international data: compared with their poorer counterparts, nations with a high level of GDP per person have everything from better childhood nutrition to more computers per household. A large GDP does not ensure that all of a nation’s citizens are happy, but it may be the best recipe for happiness that macroeconomists have to offer.

This chapter addresses four groups of questions about the sources and uses of a nation’s GDP:

How much do the firms in the economy produce? What determines a nation’s total income?

Who gets the income from production? How much goes to compensate workers, and how much goes to compensate owners of capital?

Who buys the output of the economy? How much do households purchase for consumption, how much do households and firms purchase for investment, and how much does the government buy for public purposes?

What equilibrates the demand for and supply of goods and services? What ensures that desired spending on consumption, investment, and government purchases equals the level of production?

To answer these questions, we must examine how the various parts of the economy interact.

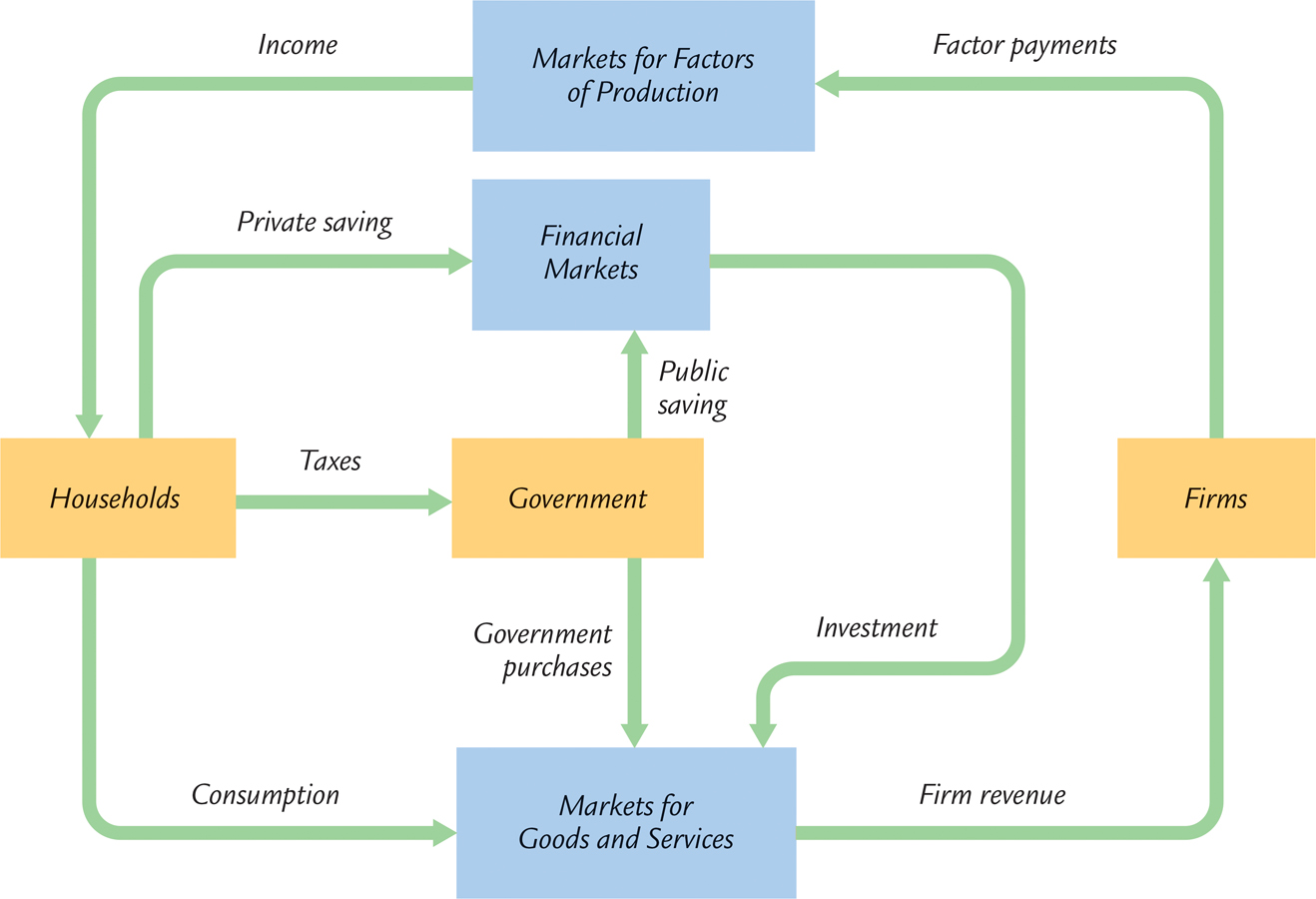

A good place to start is the circular flow diagram. In Chapter 2 we traced the circular flow of dollars in a hypothetical economy that used one input (labor services) to produce one output (bread). Figure 3-1 more accurately reflects how real economies function. It shows the linkages among the economic actors—

FIGURE 3-1

48

Let’s look at the flow of dollars from the viewpoints of these economic actors. Households receive income and use it to pay taxes to the government, to consume goods and services, and to save through the financial markets. Firms receive revenue from the sale of the goods and services they produce and use it to pay for the factors of production. Households and firms borrow in financial markets to buy investment goods, such as houses and factories. The government receives revenue from taxes and uses it to pay for government purchases. Any excess of tax revenue over government spending is called public saving, which can be either positive (a budget surplus) or negative (a budget deficit).

49

In this chapter we develop a basic classical model to explain the economic interactions depicted in Figure 3-1. We begin with firms and look at what determines their level of production (and thus the level of national income). Then we examine how the markets for the factors of production distribute this income to households. Next, we consider how much of this income households consume and how much they save. In addition to discussing the demand for goods and services arising from the consumption of households, we discuss the demand arising from investment and government purchases. Finally, we come full circle and examine how the demand for goods and services (the sum of consumption, investment, and government purchases) and the supply of goods and services (the level of production) are brought into balance.