4-2 The Role of Banks in the Monetary System

Earlier, we introduced the concept of “money supply” in a highly simplified manner. We defined the quantity of money as the number of dollars held by the public, and we assumed that the Federal Reserve controls the supply of money by increasing or decreasing the number of dollars in circulation through open-

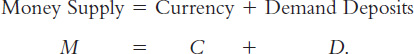

In this section we see that the money supply is determined not only by Fed policy but also by the behavior of households (which hold money) and banks (in which money is held). We begin by recalling that the money supply includes both currency in the hands of the public and deposits (such as checking account balances) at banks that households can use on demand for transactions. If M denotes the money supply, C currency, and D demand deposits, we can write

89

To understand the money supply, we must understand the interaction between currency and demand deposits and how the banking system, together with Fed policy, influences these two components of the money supply.

100-Percent-Reserve Banking

We begin by imagining a world without banks. In such a world, all money takes the form of currency, and the quantity of money is simply the amount of currency that the public holds. For this discussion, suppose that there is $1,000 of currency in the economy.

Now introduce banks. At first, suppose that banks accept deposits but do not make loans. The only purpose of the banks is to provide a safe place for depositors to keep their money.

The deposits that banks have received but have not lent out are called reserves. Some reserves are held in the vaults of local banks throughout the country, but most are held at a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve. In our hypothetical economy, all deposits are held as reserves: banks simply accept deposits, place the money in reserve, and leave the money there until the depositor makes a withdrawal or writes a check against the balance. This system is called 100–

Suppose that households deposit the economy’s entire $1,000 in Firstbank. Firstbank’s balance sheet—its accounting statement of assets and liabilities—

|

Firstbank’s Balance Sheet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

||

|

Reserves |

$1,000 |

Deposits |

$1,000 |

The bank’s assets are the $1,000 it holds as reserves; the bank’s liabilities are the $1,000 it owes to depositors. Unlike banks in our economy, this bank is not making loans, so it will not earn profit from its assets. The bank presumably charges depositors a small fee to cover its costs.

What is the money supply in this economy? Before the creation of Firstbank, the money supply was the $1,000 of currency. After the creation of Firstbank, the money supply is the $1,000 of demand deposits. A dollar deposited in a bank reduces currency by one dollar and raises deposits by one dollar, so the money supply remains the same. If banks hold 100 percent of deposits in reserve, the banking system does not affect the supply of money.

Fractional–Reserve Banking

Now imagine that banks start to use some of their deposits to make loans—

90

Here is Firstbank’s balance sheet after it makes a loan:

|

Firstbank’s Balance Sheet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

||

|

Reserves |

$200 |

Deposits |

$1,000 |

|

Loans |

$800 |

||

This balance sheet assumes that the reserve–

Notice that Firstbank increases the supply of money by $800 when it makes this loan. Before the loan is made, the money supply is $1,000, equaling the deposits in Firstbank. After the loan is made, the money supply is $1,800: the depositor still has a demand deposit of $1,000, but now the borrower holds $800 in currency. Thus, in a system of fractional–

The creation of money does not stop with Firstbank. If the borrower deposits the $800 in another bank (or if the borrower uses the $800 to pay someone who then deposits it), the process of money creation continues. Here is the balance sheet of Secondbank:

|

Secondbank’s Balance Sheet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

||

|

Reserves |

$160 |

Deposits |

$800 |

|

Loans |

$640 |

|

|

Secondbank receives the $800 in deposits, keeps 20 percent, or $160, in reserve, and then loans out $640. Thus, Secondbank creates $640 of money. If this $640 is eventually deposited in Thirdbank, this bank keeps 20 percent, or $128, in reserve and loans out $512, resulting in this balance sheet:

|

Thirdbank’s Balance Sheet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

||

|

Reserves |

$128 |

Deposits |

$640 |

|

Loans |

$512 |

|

|

The process goes on and on. With each deposit and subsequent loan, more money is created.

91

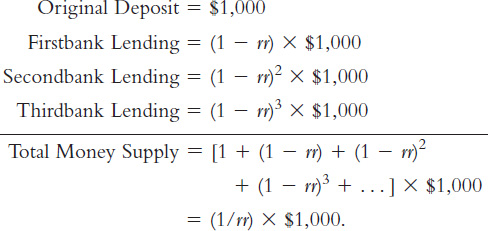

This process of money creation can continue forever, but it does not create an infinite amount of money. Letting rr denote the reserve–

Each $1 of reserves generates $(1/rr) of money. In our example, rr = 0.2, so the original $1,000 generates $5,000 of money.4

The banking system’s ability to create money is the primary difference between banks and other financial institutions. As we first discussed in Chapter 3, financial markets have the important function of transferring the economy’s resources from those households that wish to save some of their income for the future to those households and firms that wish to borrow to buy investment goods to be used in future production. The process of transferring funds from savers to borrowers is called financial intermediation. Many institutions in the economy act as financial intermediaries: the most prominent examples are the stock market, the bond market, and the banking system. Yet, of these financial institutions, only banks have the legal authority to create assets (such as checking accounts) that are part of the money supply. Therefore, banks are the only financial institutions that directly influence the money supply.

Note that although the system of fractional–

Bank Capital, Leverage, and Capital Requirements

The model of the banking system presented so far is simplified. That is not necessarily a problem; after all, all models are simplified. But it is worth drawing attention to one particular simplifying assumption.

92

In the bank balance sheets we just examined, a bank takes in deposits and either uses them to make loans or holds them as reserves. Based on this discussion, you might think that it does not take any resources to open up a bank. That is, however, not true. Opening a bank requires some capital. That is, the bank owners must start with some financial resources to get the business going. Those resources are called bank capital or, equivalently, the equity of the bank’s owners.

Here is what a more realistic balance sheet for a bank would look like:

|

Realbank’s Balance Sheet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities and Owners’ Equity |

||

|

Reserves |

$200 |

Deposits |

$750 |

|

Loans |

$500 |

Debt |

$200 |

|

Securities |

$300 |

Capital (owners’ equity) |

$50 |

The bank obtains resources from its owners, who provide capital, and also by taking in deposits and issuing debt. It uses these resources in three ways. Some funds are held as reserves; some are used to make bank loans; and some are used to buy financial securities, such as government or corporate bonds. The bank allocates its resources among these asset classes, taking into account the risk and return that each offers and any regulations that restrict its choices. The reserves, loans, and securities on the left side of the balance sheet must equal, in total, the deposits, debt, and capital on the right side of the balance sheet.

This business strategy relies on a phenomenon called leverage, which is the use of borrowed money to supplement existing funds for purposes of investment. The leverage ratio is the ratio of the bank’s total assets (the left side of the balance sheet) to bank capital (the one item on the right side of the balance sheet that represents the owners’ equity). In this example, the leverage ratio is $1000/$50, or 20. This means that for every dollar of capital that the bank owners have contributed, the bank has $20 of assets and, thus, $19 of deposits and debts.

One implication of leverage is that, in bad times, a bank can lose much of its capital very quickly. To see how, let’s continue with this numerical example. If the bank’s assets fall in value by a mere 5 percent, then the $1,000 of assets is now worth only $950. Because the depositors and debt holders have the legal right to be paid first, the value of the owners’ equity falls to zero. That is, when the leverage ratio is 20, a 5 percent fall in the value of the bank assets leads to a 100 percent fall in bank capital. The fear that bank capital may be running out, and thus that depositors may not be fully repaid, is typically what generates bank runs when there is no deposit insurance.

One restriction that bank regulators put on banks is that the banks must hold sufficient capital. The goal of such a capital requirement is to ensure that banks will be able to pay off their depositors and other creditors. The amount of capital required depends on the kind of assets a bank holds. If the bank holds safe assets such as government bonds, regulators require less capital than if the bank holds risky assets such as loans to borrowers whose credit is of dubious quality.

93

The arcane issues of bank capital and leverage are usually left to bankers, regulators, and financial experts, but they became prominent topics of public debate during and after the financial crisis of 2008–

For the rest of this chapter, we can put aside the issues of bank capital and leverage. But they will resurface when we discuss financial crises in Chapter 12 and Chapter 20.