7-3 Real-Wage Rigidity and Structural Unemployment

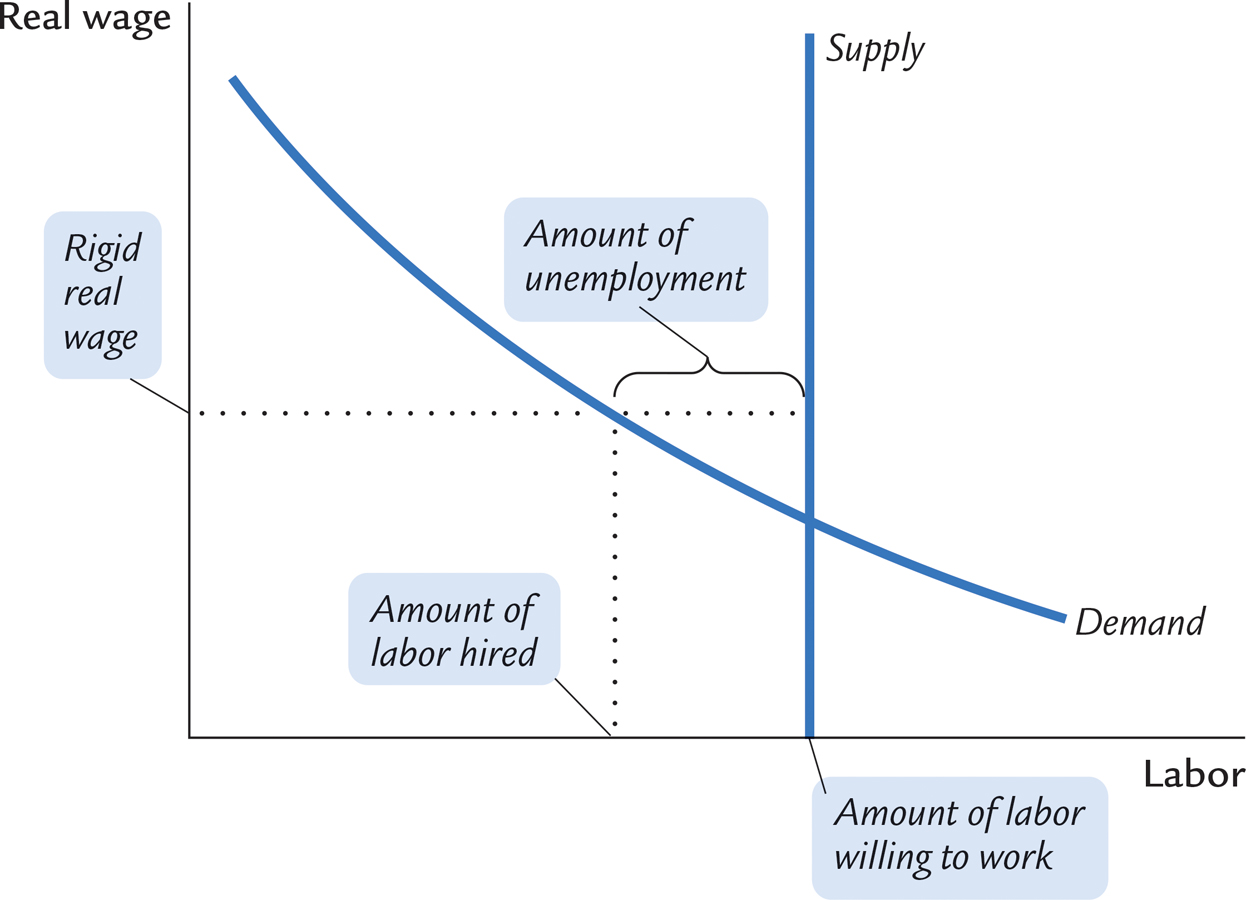

A second reason for unemployment is wage rigidity—the failure of wages to adjust to a level at which labor supply equals labor demand. In the equilibrium model of the labor market, as outlined in Chapter 3, the real wage adjusts to equilibrate labor supply and labor demand. Yet wages are not always flexible. Sometimes the real wage is stuck above the market-

Figure 7-3 shows why wage rigidity leads to unemployment. When the real wage is above the level that equilibrates supply and demand, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. Firms must in some way ration the scarce jobs among workers. Real-

FIGURE 7-3

190

The unemployment resulting from wage rigidity and job rationing is sometimes called structural unemployment. Workers are unemployed not because they are actively searching for the jobs that best suit their individual skills but because there is a fundamental mismatch between the number of people who want to work and the number of jobs that are available. At the going wage, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity of labor demanded; many workers are simply waiting for jobs to open up.

To understand wage rigidity and structural unemployment, we must examine why the labor market does not clear. When the real wage exceeds the equilibrium level and the supply of workers exceeds the demand, we might expect firms to lower the wages they pay. Structural unemployment arises because firms fail to reduce wages despite an excess supply of labor. We now turn to three causes of this wage rigidity: minimum-

Minimum-Wage Laws

The government causes wage rigidity when it prevents wages from falling to equilibrium levels. Minimum-

191

Economists believe that the minimum wage has its greatest impact on teenage unemployment. The equilibrium wages of teenagers tend to be low for two reasons. First, because teenagers are among the least skilled and least experienced members of the labor force, they tend to have low marginal productivity. Second, teenagers often take some of their “compensation” in the form of on-

Many economists have studied the impact of the minimum wage on teenage employment. These researchers compare the variation in the minimum wage over time with the variation in the number of teenagers with jobs. These studies find that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduces teenage employment by 1 to 3 percent.4

The minimum wage is a perennial source of political debate. Advocates of a higher minimum wage view it as a way to raise the income of the working poor. Certainly, the minimum wage provides only a meager standard of living: in the United States, a single parent with one child working full time at a minimum-

Opponents of a higher minimum wage claim that it is not the best way to help the working poor. They contend not only that the increased labor costs raise unemployment but also that the minimum wage is poorly targeted. Many minimum-

Many economists and policymakers believe that tax credits are a better way to increase the incomes of the working poor. The earned income tax credit is an amount that poor working families are allowed to subtract from the taxes they owe. For a family with very low income, the credit exceeds its taxes, and the family receives a payment from the government. Unlike the minimum wage, the earned income tax credit does not raise labor costs to firms and, therefore, does not reduce the quantity of labor that firms demand. It has the disadvantage, however, of reducing the government’s tax revenue.

192

CASE STUDY

The Characteristics of Minimum-

Who earns the minimum wage? The question can be answered using the Current Population Survey, the labor-

About 76 million American workers are paid hourly, representing 59 percent of all wage and salary workers. Of these workers, 1.5 million reported earning exactly the prevailing minimum wage, and another 1.8 million reported earning less. A reported wage below the minimum is possible because some workers are exempt from the statute (newspaper delivery workers, for example), because enforcement is imperfect, and because some workers round down when reporting their wages on surveys.

Minimum-

wage workers are more likely to be women than men. About 3 percent of men and 5 percent of women reported wages at or below the prevailing federal minimum. Minimum-

wage workers tend to be young. About half of all hourly- paid workers earning the minimum wage or less were under age 25. Among teenagers, about 20 percent earned the minimum wage or less, compared with about 3 percent of workers age 25 and over. Minimum-

wage workers tend to be less educated. Among hourly- paid workers age 16 and over, about 10 percent of those without a high school diploma earned the minimum wage or less, compared with 4 percent of those with a high school diploma and 2 percent of those with a college degree. Minimum-

wage workers are more likely to be working part time. Among part- time workers (those who usually work less than 35 hours per week), 10 percent were paid the minimum wage or less, compared to 2 percent of full- time workers. The industry with the highest proportion of workers with reported hourly wages at or below the minimum wage was leisure and hospitality (about 19 percent). Just over one-

half of all workers paid at or below the minimum wage were employed in this industry, primarily in food services and drinking places. For many of these workers, tips supplement the hourly wages received.

These facts by themselves do not tell us whether the minimum wage is a good or bad policy, or whether it is too high or too low. But when evaluating any public policy, it is useful to keep in mind those individuals who are affected by it.5

193

Unions and Collective Bargaining

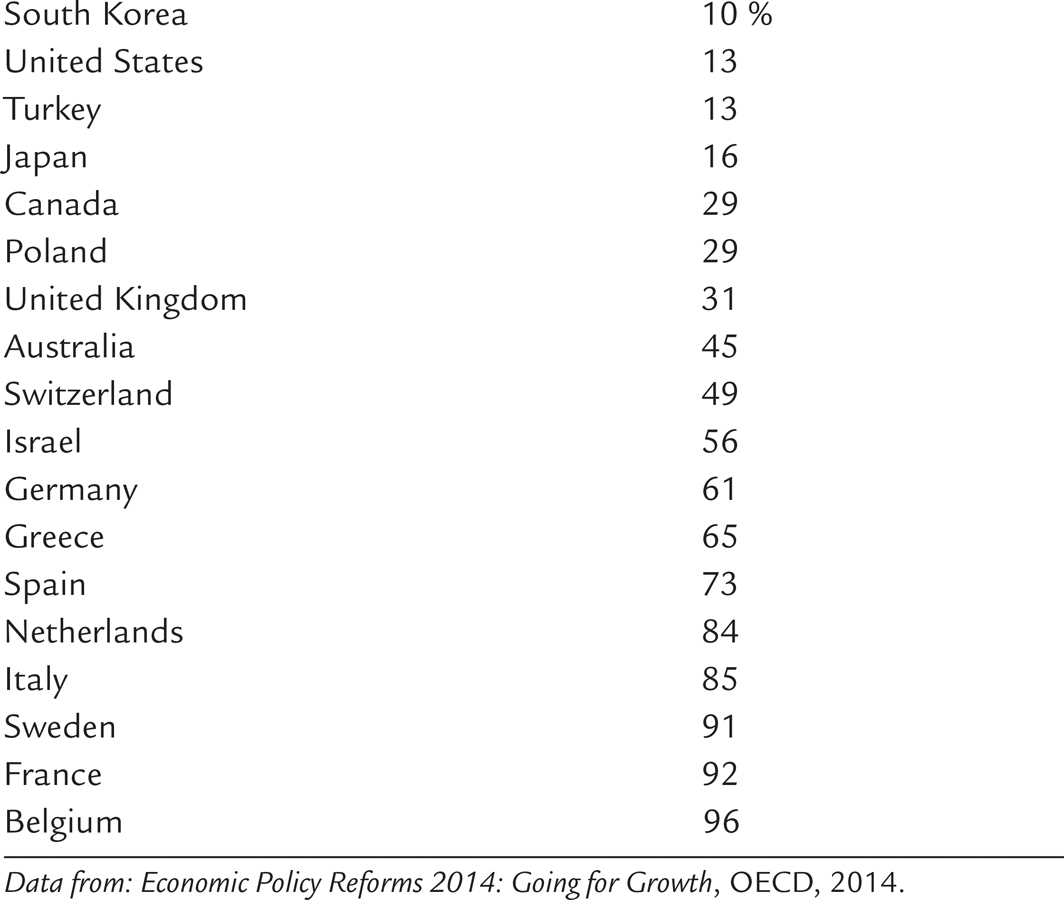

A second cause of wage rigidity is the monopoly power of unions. Table 7-1 shows the importance of unions in several major countries. In the United States, only 13 percent of workers have their wages set through collective bargaining. In most European countries, unions play a much larger role.

TABLE 7-1

TABLE 7-

The wages of unionized workers are determined not by the equilibrium of supply and demand but by bargaining between union leaders and firm management. Often, the final agreement raises the wage above the equilibrium level and allows the firm to decide how many workers to employ. The result is a reduction in the number of workers hired, a lower rate of job finding, and an increase in structural unemployment.

Unions can also influence the wages paid by firms whose workforces are not unionized because the threat of unionization can keep wages above the equilibrium level. Most firms dislike unions. Unions not only raise wages but also increase the bargaining power of labor on many other issues, such as hours of employment and working conditions. A firm may choose to pay its workers high wages to keep them happy and discourage them from forming a union.

The unemployment caused by unions and by the threat of unionization is an instance of conflict between different groups of workers—

194

The conflict between insiders and outsiders is resolved differently in different countries. In some countries, such as the United States, wage bargaining takes place at the level of the firm or plant. In other countries, such as Sweden, wage bargaining takes place at the national level—

Efficiency Wages

Efficiency-

Economists have proposed various theories to explain how wages affect worker productivity. One efficiency-

A second efficiency-

A third efficiency-

A fourth efficiency-

195

Although these four efficiency-

CASE STUDY

Henry Ford’s $5 Workday

In 1914 the Ford Motor Company started paying its workers $5 per day. The prevailing wage at the time was between $2 and $3 per day, so Ford’s wage was well above the equilibrium level. Not surprisingly, long lines of job seekers waited outside the Ford plant gates hoping for a chance to earn this high wage.

What was Ford’s motive? Henry Ford later wrote, “We wanted to pay these wages so that the business would be on a lasting foundation. We were building for the future. A low wage business is always insecure…. The payment of five dollars a day for an eight hour day was one of the finest cost-

From the standpoint of traditional economic theory, Ford’s explanation seems peculiar. He was suggesting that high wages imply low costs. But perhaps Ford had discovered efficiency-

Evidence suggests that paying such a high wage did benefit the company. According to an engineering report written at the time, “The Ford high wage does away with all the inertia and living force resistance…. The workingmen are absolutely docile, and it is safe to say that since the last day of 1913, every single day has seen major reductions in Ford shops’ labor costs.” Absenteeism fell by 75 percent, suggesting a large increase in worker effort. Alan Nevins, a historian who studied the early Ford Motor Company, wrote, “Ford and his associates freely declared on many occasions that the high wage policy had turned out to be good business. By this they meant that it had improved the discipline of the workers, given them a more loyal interest in the institution, and raised their personal efficiency.”7

196